Levitra enthält Vardenafil, das eine kürzere Wirkdauer als Tadalafil hat, dafür aber schnell einsetzt. Männer, die diskret bestellen möchten, suchen häufig nach levitra kaufen ohne rezept. Dabei spielt die rechtliche Lage in der Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle.

Dentalbooks.bg

Contemporary Restoration of

TREATED TEETH

Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Nadim Z. Baba, dmd, msdProfessor of Restorative DentistryDirectorHugh Love Center for Research and Education in TechnologyLoma Linda University School of DentistryLoma Linda, California

Quintessence Publishing Co, IncChicago, Berlin, Tokyo, London, Paris, Milan, Barcelona, Beijing,Istanbul, Moscow, New Delhi, Prague, São Paulo, Seoul, Singapore, and Warsaw

Foreword viiPreface viiiContributors ix

Part I: Treatment Planning for Endodontically Treated Teeth

Impact of Outcomes Data on Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

3

1

Charles J. Goodacre and W. Patrick Naylor

Treatment Planning Considerations for Endodontically Treated Teeth

19

2

Robert A. Handysides and Leif K. Bakland

Treatment Options and Materials for Endodontically Treated Teeth

33

3

Nadim Z. Baba and Charles J. Goodacre

Part II: Methods of Restoration for Endodontically Treated

Principles for Restoration of Endodontically Treated Teeth

61

4

Nadim Z. Baba, Charles J. Goodacre, and Fahad A. Al-Harbi

Cementation of Posts and Provisional Restoration

75

5

Faysal G. Succaria and Steven M. Morgano

Tooth Whitening and Management of Discolored Endodontically

6 Treated Teeth

91

Part III: Management of Severely Damaged Endodontically

Crown Lengthening

107

7

Nikola Angelov

Preprosthetic Orthodontic Tooth Eruption

115

8

Joseph G. Ghafari

Intra-alveolar Transplantation

127

9

Antoanela Garbacea, Nadim Z. Baba, and Jaime L. Lozada

Autotransplantation and Replantation

137

10

Leif K. Bakland and Mitsuhiro Tsukiboshi

Osseointegrated Dental Implants

149

11

Juan Mesquida, Aladdin J. Al-Ardah, Hugo Campos Leitão, Jaime L. Lozada,

and Aina Mesquida

Part IV: Treatment of Complications and Failures

Repair of Perforations in Endodontically Treated Teeth

167

12

George Bogen, C. John Munce, and Nicholas Chandler

Removal of Posts

181

13

Ronald Forde, Nadim Z. Baba, and Balsam Jekki

Removal of Broken Instruments from the Root Canal System

195

14

David E. Jaramillo

Endodontic Treatment of a Tooth with a Prosthetic Crown

201

15

Mathew T. Kattadiyil

Retrofitting a Post to an Existing Crown

207

16

Nadim Z. Baba, Tony Daher, and Rami Jekki

It is an honor to have been invited to write the foreword

Dentists encountering treatment planning dilemmas, such

for Dr Nadim Baba's text on the restoration of endodonti-

as determining when to extract a compromised tooth and

cally treated teeth. The last book on this topic, published by

when to retain it and restore it, can find the answers to most

Quintessence, was authored by Shillingburg and Kessler in

of their questions in this first-rate text. Traditional principles

1982. Three decades later, this new book is much needed

and techniques are reviewed and reinforced, along with

and long overdue.

modern materials and methods, all with a firm foundation

Dr Baba's interest in the restoration of pulpless teeth

in the best available scientific evidence and with an em-

dates back to his graduate-school days. I served as his

phasis on clinical studies. Many of the chapters provide

program director and his principal research advisor during

comprehensive, step-by-step descriptions of technical pro-

his studies at Boston University in the postdoctoral pros-

cedures with accompanying illustrations to guide the read-

thodontic program, where the title of his master's project

er through all aspects of restoring pulpless teeth, including

and thesis was "The Effect of Eugenol and Non-eugenol

fabrication of various foundation restorations, cementation

Endodontic Sealers on the Retention of Three Prefabricated

techniques, and methods of provisionalization of endodon-

Posts Cemented with a Resin Composite Cement." Dr Baba

tically treated teeth. Preprosthetic adjunctive procedures,

certainly has come a long way since receiving his certifi-

such as surgical crown lengthening, repair of perforations,

cate of advanced graduate study and master of science in

and orthodontic measures, are also described and illus-

dentistry degree in 1999. He is now a Diplomate of the

American Board of Prosthodontics and a full professor at

Dr Baba has assembled a group of renowned experts on

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, and he is about

various topics related to the restoration of pulpless teeth,

to publish this comprehensive book on the restoration of

and these experts have collectively produced this outstand-

endodontically treated teeth.

ing text, which will remain a definitive reference for years

This new text has a wealth of evidence-based information

to come. The profession as a whole is very fortunate to

on all facets of restoration of endodontically treated teeth

have this text. Many thanks must go to Dr Baba for under-

and will serve as an indispensable reference not only for

taking this monumental task and to all contributing authors

dentists involved in the restoration of pulpless teeth, such

for their time and efforts in helping Dr Baba produce this

as general practitioners and prosthodontists, but also for

new book on such a very important subject.

dentists who do not place restorations but are engaged in

planning treatment for structurally compromised teeth, such

as endodontists, periodontists, and oral surgeons. With

Steven M. Morgano, dmd

the well-documented success of osseointegrated implant-

Professor of Restorative Sciences and Biomaterials

supported fixed restorations, combined with a better un-

Director, Division of Postdoctoral Prosthodontics

derstanding of the factors that can influence the prognosis

Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental

of severely broken down teeth, the profession's approach

to planning treatment for these teeth has evolved, and this

Boston, Massachusetts

text offers a well-balanced, contemporary approach to the

topic of treatment planning.

My interest in the restoration of endodontically treated

teeth dates back to my graduate-school days at Boston Uni-

versity. When working on my master's project and thesis

and later while studying for the American Board of Pros-

I wish to express my appreciation and indebtedness to

thodontics exam, I realized that very few books dealt with

all my friends and colleagues who contributed chapters,

the restoration of pulpless teeth. The first book on that topic

sections of chapters, or clinical cases in specific areas in

was published by Quintessence in 1982; two decades

which they are experts. Without them the book would not

later, three books were published but all were somewhat

have been possible.

limited in their scope. They dealt mainly with fiber posts,

I would like to take the opportunity to thank Leif Bakland,

their characteristics, and their clinical applications.

Zouheir Salamoun, W. Patrick Naylor, and the dean of

This book is primarily intended to be a manuscript that

my school, Loma Linda University, Charles J. Goodacre,

reviews the basic principles of diagnosis and treatment

for their counsel and help during the preparation of the

planning and describes numerous treatment options and

the techniques recommended for contemporary treatment

Most importantly, I extend my special thanks to Ms Lisa

of endodontically treated teeth. The purpose of this book is

Bywaters and the staff of Quintessence Publishing for their

to provide general dentists, endodontists, prosthodontists,

professionalism and guidance in bringing my book to life.

and dental students (postgraduate and predoctoral) with a

I also would like to acknowledge my teachers and men-

comprehensive review of the literature and evidence-based

tors who had a great impact on my visions, attitude, and

information for the treatment of endodontically treated

career: Pierre Boudrias, Hideo Yamamoto, Steven M. Mor-

teeth, keeping in mind the integration of systematic assess-

gano, David Baraban (deceased), and Charles J. Goodacre.

ments of clinically relevant scientific evidence.

They remind me of the Lebanese-American poet and writer

Four major themes are discussed. The first part focuses

Gibran Khalil Gibran, who said: "The teacher who is indeed

on treatment planning, treatment options, and materials

wise does not bid you to enter the house of his wisdom but

used for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth. The

rather leads you to the threshold of your mind."

second part reviews the principles and methods of restora-

I feel blessed, lucky, and proud to have had the chance

tion along with cementation, provisional restoration, and

to know and work with each one of these people in various

management of discolored endodontically treated teeth.

stages of my professional career.

The third part describes the different aspects of the man-

agement of severely damaged pulpless teeth. In the final

part, treatment of complications and failures is reported.

Aladdin J. Al-Ardah, dds, ms

Nicholas Chandler, bds, msc, phd

Assistant Professor

Associate Professor of Endodontics

Advanced Education Program in Implant Dentistry

University of Otago School of Dentistry

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Dundin, New Zealand

Loma Linda, California

Tony Daher, dds, msed

Fahad A. Al-Harbi, bds, msd, dscd

Associate Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Dean and Assistant Professor

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

College of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

University of Dammam

Dammam, Saudi Arabia

University of California at Los Angeles

Nikola Angelov, dds, ms, phd

Los Angeles, California

Professor and Director

Predoctoral Program in Periodontics

Ronald Forde, dds, ms

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Chair and Assistant Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Nadim Z. Baba, dmd, msd

Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Antoanela Garbacea, dds

Hugh Love Center for Research and Education in Technology

Santa Rosa, California

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Joseph G. Ghafari, dmd

Head and Professor

Leif K. Bakland, dds

Division of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

Ronald E. Buell Professor of Endodontics

Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

American University of Beirut Medical Center

Loma Linda, California

George Bogen, dds

Professor of Orthodontics

Private practice limited to endodontics

Lebanese University School of Dentistry

Los Angeles, California

Adjunct Professor of Orthodontics

New York University College of Dentistry

New York, New York

Charles J. Goodacre, dds, msd

Aina Mesquida, dds

Dean and Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Advanced Education Program in Implant Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Robert A. Handysides, dds

Chair and Associate Professor of Endodontics

Juan Mesquida, dds

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Assistant Professor

Loma Linda, California

Advanced Education Program in Implant Dentistry

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

David E. Jaramillo, dds

Loma Linda, California

Clinic Director and Associate Professor of Endodontics

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Steven M. Morgano, dmd

Loma Linda, California

Professor of Restorative Sciences and Biomaterials

Balsam F. Jekki, bds

Division of Postdoctoral Prosthodontics

Assistant Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Boston, Massachusetts

Rami Jekki, dds

C. John Munce, dds

Assistant Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Assistant Professor of Endodontics

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Loma Linda, California

Mathew T. Kattadiyil, dds, mds, ms

Assistant Professor of Endodontics

Associate Professor of Restorative Dentistry

University of Southern California Ostrow School of

Advanced Specialty Education Program in Prosthodontics

Los Angeles, California

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

W. Patrick Naylor, dds, mph, ms

Hugo Campos Leitão, dmd, msd

Advanced Dental Education

Assistant Professor in Periodontics

Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Universitat Internacional de Catalunya

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Yiming Li, dds, msd, phd

Faysal G. Succaria, dds, msd

Professor of Restorative Dentistry

Chair and Assistant Professor

Department of Prosthodontics

Center for Dental Research

Boston University Institute for Dental Research and

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Jaime L. Lozada, dmd

Mitsuhiro Tsukiboshi, dds, phd

Professor and Director

Advanced Education Program in Implant Dentistry

Tsukiboshi Dental Clinic

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry

Loma Linda, California

Treatment Planning for

Endodontical y Treated Teeth

Impact of Outcomes Data on

1. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Treatment Planning Considerations

2. for Endodontically Treated Teeth3. Treatment Options and Materials

for Endodontically Treated Teeth

2 Treatment Planning Considerations for Endodontically Treated Teeth

Fig 2-4 (a) The complexity of the root canal system is well illustrated in these sections of maxillary molars. Note the variety of canal configurations

in the mesiobuccal roots and in particular the location of the second mesiobuccal canal in the molar on the right. (b) A radiograph of a maxillary

molar seems to show two palatal roots (arrows). (c) On the patient's request, the tooth was extracted; two palatal roots were identified (arrows).

In addition, Schilder12 named four biologic objectives for

Assessment of other conditions

these preparations:

1. Treatment procedures are confined to the roots.

2. Necrotic debris is not forced beyond the apical foram-

Fracture lines involving cusps of teeth have been a prob-

lem in dentistry, probably throughout human history. The

3. All pulp tissues are removed from the root canal space.

pain associated with such fracture lines was described by

4. Sufficient space exists for intracanal medicaments and

Gibbs,16 who termed it cuspal fracture odontalgia. Every

dentist has probably had a patient who complains about

pain on chewing and later shows up with the broken-off

These objectives provide a basis for assessing the qual-

cusp, usually from a premolar tooth. Whether or not the

ity of the endodontic procedure prior to restoration of the

pulp is directly involved (by exposure), it is usually neces-

tooth. Deviation from the original canal shape is referred to

sary to complete RCT before the tooth is restored. Diagno-

as transportation of the canal. The greater the transporta-

sis of a fracture line under a cusp, before it breaks off, can

tion, the greater the likelihood of a poor endodontic out-

be a challenge and will be discussed in the next section on

come, resulting in the need for either endodontic retreat-

ment or extraction of the tooth.

Teeth may develop cracks and fracture for a number of

reasons, including trauma, excessive masticatory forces,

Root canal systems

and iatrogenic incidents. Regardless of etiology, when

cracks or fractures develop in dental hard tissues it is not

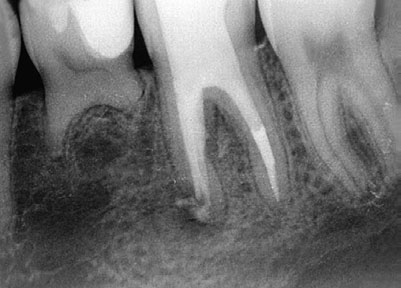

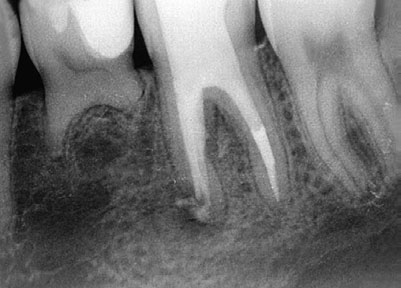

The root canal system is complex (Fig 2-4), and its anatomy

possible to repair them, except for a short period of time

has been studied extensively for many years. Of special

with bonding agents. In contrast, bone and cartilage rou-

interest in the current context, Weine et al13 called atten-

tinely undergo repair following fracture. Although tooth

tion to the frequent presence of two canals in the mesio-

fractures and cracks cannot be healed, it is possible in

buccal roots of maxillary molars. Pineda and Kuttler14

many cases to maintain such teeth for various periods of

and Vertucci15 developed classification systems for canal

time following identification and diagnosis.

configurations in individual roots. Research in root canal

For convenience in discussing cracks and fractures, three

morphology has led to descriptions of more than 20 canal

categories will be used: enamel craze lines, infractions,

and vertical root fractures (VRFs).

These considerations are important for the evaluation of

a tooth that has undergone RCT. They also point to the chal-

Enamel craze lines. Craze lines are small cracks that are

lenges inherent to treating teeth with endodontic disease

confined to the enamel of teeth (Fig 2-5). They are not typi-

prior to restoration to full function. Achieving full function

cally visible unless light rays highlight them incidentally.

requires that the treatment-planning process be a teamwork

They develop over time, so they probably can be found in

process: RCT can be performed on almost any tooth, but

most teeth eventually. Occasionally they will show stains

restorability must be determined prior to the endodontic

from exposure to liquids such as coffee and red wine. Be-

component of treatment. Communication among the vari-

cause these cracks are confined to enamel, they have no

ous treating dentists before, during, and after RCT offers

pulpal impact, and no treatment is necessary, except op-

the best possibility of an optimal outcome.

Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Fig 2-5 Enamel craze lines (arrow) are common and pre-

Fig 2-6 (a) Infractions (arrow) can be identified visually with the help of dyes, in

sent no particular problem other than their potential for

this case a red dye. Infractions usually run in a mesiodistal direction; they may be

asymptomatic or associated with pain on chewing and cold stimuli. (b) A tooth

extracted because of symptoms associated with an infraction shows the presence of

the infraction (arrow). They typically originate in the crown of the tooth and pro-

gress in an apical direction. (c) On rare occasions, infractions run in a faciolingual

tional bleaching if they are stained. There is no evidence

that can mimic trigeminal neuralgia; chronic orofacial pain

that craze lines progress to involve more than enamel.

can also develop. The wide range of pain experiences is

probably why Cameron18 used the term syndrome to de-

Infractions (cracked teeth). The term cracked tooth is com-

scribe this dental situation. The etiology of infractions is

monly used to describe a tooth that has developed an

probably in most cases related to occlusal forces, whether

infraction, which is defined as "a fracture of hard tissue

from regular daily chewing or isolated trauma such as

in which the parts have not separated"17 (Fig 2-6). Cam-

blows to the underside of the mandible.19–25

eron18 incorrectly defined this condition as cracked tooth

It is likely that teeth with infractions become symptomatic

syndrome; the use of syndrome is not appropriate for pain

when the infractions become invaded by bacteria26 (Fig

associated with fractures in teeth. It is, however, a situation

2-7). Bacteria stimulate inflammation in the pulp, whether

with a variety of symptoms, and diagnosis can be very

or not the infraction communicates directly with the pulp tis-

sue. The inflamed tissue is responsible for the exaggerated

Mandibular molars and maxillary molars and premo-

cold response. It is also likely that the tooth will become

lars are the teeth most frequently associated with infrac-

sensitive to biting when the infraction progresses from the

tions. The teeth usually have vital pulps and the infractions

tooth crown to the root, and the bacteria that will soon

typically run in a mesiodistal direction. They begin in the

occupy the infraction then stimulate an inflammatory re-

crowns of teeth and progress in an apical direction. Not all

sponse in the adjacent periodontal ligament (PDL).

teeth with infractions are symptomatic, but when symptoms

Diagnosis of infractions is complicated by many factors.

develop they can range from pain on chewing, to an exag-

Because infractions are usually located in a mesiodistal di-

gerated response to cold stimuli, to severe pain episodes

rection in the crown, they are not visible on radiographs.

3 Treatment Options and Materials for Endodontically Treated Teeth

Fig 3-17 (a and b) A provisional fixed dental prosthesis is fabricated in resin composite material. The restoration has proper contours, thickness,

proximal contacts, and adequate occlusal contacts. (c) Gutta-percha is removed from the orifice of the canals to aid in retention of the core. (d) A

carbide rotary cutting instrument is used to make an occlusal access opening on the provisional prosthesis, toward the center of the foundation. (e)

The FPD is cemented, and the amalgam is condensed in the prepared post spaces. (f and g) A tapered rotary cutting instrument is used carefully

to make a vertical groove in the lingual surface in order to section the provisional prosthesis. (h and i) The amalgam foundation is refined for the

definitive tooth preparation, and a final impression is taken.

3. Remove 1 to 2 mm of gutta-percha from the orifice of

endodontic plugger. Fill the remaining pulp chamber

the canals to aid in retention of the core. This is only

with amalgam up to the occlusal surface of the pro-

necessary when the pulp chamber is smaller than 3

visional FPD to ensure an adequate seal, and make

mm in depth (Fig 3-17c).

occlusal adjustments as needed (Fig 3-17e).

4. Use a carbide rotary cutting instrument to make an oc-

9. At the following appointment, carefully section the pro-

clusal access opening in the abutment retainer toward

visional FPD by using a tapered rotary cutting instru-

the center of the foundation.

ment to make a vertical groove in the buccal surface

5. Place the modified provisional FPD on the remaining

(Figs 3-17f and 3-17g).

tooth structure, and confirm adequate access to the

10. Refine the amalgam foundation for the definitive tooth

cavity for ideal amalgam placement and condensation

preparation, and take the definitive impression (Figs

(Fig 3-17d).

3-17h and 3-17i).

6. Confirm proper fit and marginal adaptation of the pro-

11. Fabricate and cement a new provisional FPD with pro-

visional FPD.

visional cement.

7. Cement the modified provisional FPD with a small

amount of provisional cement placed only on the mar-

The same procedure is used when a provisional crown is

gins of the provisional FPD.

used as a matrix for an amalgam core buildup (Fig 3-18).

8. Condense the first increments of amalgam into the pre-

pared post spaces using a periodontal probe or an

Types of Posts and Cores

Fig 3-18 (a) The mandibular right first molar was endodontically treated and presented with enough remaining coronal tooth structure and adequate

depth of the pulpal chamber. (b) Tooth preparation is finished, and the post space is prepared in the distal canal to receive a prefabricated metallic

post. (c) The provisional crown is fabricated using resin material with proper contours, thickness, proximal contact, and adequate occlusal contacts.

(d) An occlusal access opening in the provisional crown is made so only a peripheral shell of resin is retained using a carbide rotary cutting

instrument. The provisional crown is cemented with a luting agent. The length of the prefabricated post is adjusted to the appropriate height, and

the post is cemented with zinc phosphate cement. (e) The amalgam is condensed into the prepared post space. (f and g) After the amalgam has

hardened or at a subsequent appointment, the provisional crown is sectioned carefully by making a vertical groove in the labial surface using

a tapered rotary cutting instrument. (h) The amalgam foundation is refined for the definitive tooth preparation, and a final impression is taken.

(Courtesy of Dr Carlos E. Sabrosa, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.)

Composite resin

Oliva and Lowe255 found that composite resin cores were

not dimensionally stable when exposed to moisture. How-

Composite resin is a popular core material because it is

ever, Vermilyea et al257 found that the use of a well-fitting

easy to use and satisfies esthetic demands. Certain proper-

provisional restoration will provide the composite resin

ties of composite resins are inferior to those of amalgam

core with some degree of moisture protection. Hygroscopic

but superior to glass-ionomer materials.234,247 Kovarik et al234

expansion of composite resin cores and cements in layered

showed that composite resin is more flexible than amal-

structures with an overlying ceramic layer can generate sig-

gam. It adheres to tooth structure, may be prepared and

nificant stresses that have the potential to cause extensive

finished immediately, and has good color under all-ceramic

cracking in the overlying ceramic layer. Clinically, this im-

crowns. Composite resin appears to be an acceptable

plies that all-ceramic crown performance may be compro-

core material when substantial coronal tooth structure re-

mised if the crowns are luted to composite cores that have

mains235,248–253 but a poor choice when a significant amount

undergone hygroscopic expansion.258

of tooth structure is missing.234,254

Another disadvantage is that composite resin is dimen-

One disadvantage of composite resin cores is the insta-

sionally unstable (setting shrinkage). Shrinkage during po-

bility of the material in oral fluids (water sorption).255,256

lymerization causes stress on the adhesive bond, resulting

CH 12 Repair of Perforations in Endodontically Treated Teeth

Fig 12-8 (a) Mandibular left first molar with a mesial root periapical radiolucency in a 13-year-old asymptomatic girl. The molar exhibits both strip

and apical perforations from previous root canal treatment. (b) Strip perforation visible under the DOM at the furcal side of the mesial root (arrow).

(c) Working length determination after removal of previous obturation material. (d) White MTA canal obturation to the level of the pulpal floor. (e)

Final radiograph of obturation and the fiber post and bonded core. (f) Radiograph at 7 years, showing the complete-coverage restoration and

complete periradicular healing. The patient is asymptomatic with the molar in full function. (Courtesy of Dr Marga Ree, Amsterdam.)

Fig 12-9 (a) Maxillary left second premolar in a symptomatic 24-year-old man with a suspected post perforation to the mesiobuccal root aspect.

Note the well-circumscribed periradicular radiolucency adjacent to the perforation. (b) Completed access through the metal-ceramic crown. The

coronal aspect of the post has been uncovered. (c) Post following removal. (d) Chamber after debridement of the perforation site and preparation

for MTA placement. (e) Immediate postoperative radiograph following MTA perforation repair and subsequent completion of nonsurgical endodon-

tic retreatment. (f) Ten-month radiographic review showing complete resolution of the periradicular pathosis. The patient is asymptomatic. (Courtesy

of Dr Ryan M. Jack, Colorado Springs, CO.)

Management of Perforations

Fig 12-10 (a) Mandibular left first molar in a symptomatic 32-year-old man. Note the presence of a separated file at the mesial root apex and

concomitant transportation and perforation of the mesial root canal during previous treatment. (b) Identification of the perforation site. (c) Canal

obturation with gray MTA. (d) Surgical resection of the mesial roots, removal of the separated file, and MTA retrofill. (e) Nine-month radiographic

review. (f) Three-year recall radiograph showing complete remineralization of the osteotomy site.

calcium hydroxide followed by placement of gutta-percha

Retrograde management of perforations

as a perforation repair and filling technique.5,128–132 MTA

can be placed with or without a matrix barrier; however,

The goal of surgical repair of root perforations is to pro-

root-end resection may be indicated if the original canal

vide a reliable seal so that bacteria and their by-products

is not accessible after the repair.11 Where apical surgery

are prevented from entering the periodontium through the

is not an option, advanced techniques can also provide

root canal system. This procedure should encourage an

dedicated channels for conventional obturation after MTA

environment that promotes regeneration of the damaged

placement and hardening.

periodontal tissues and maintains immune cell surveillance.

Hemorrhage at the perforation site can be challenging

The indications for surgical treatment include excessive ex-

when nonobservable subcrestal perforations are being pre-

trusion of the repair material, combination (orthograde and

pared apically or beyond the view of the DOM. Once the

retrograde) therapies, perforations inaccessible by nonsur-

perforation is identified, 1.25% to 6.0% NaOCl provides

gical means, and failure of nonsurgical repairs3,5,15,23,106

an environment that removes inflammatory tissue, controls

(Fig 12-10). The location of the perforation is the prime

hemorrhage, disinfects the perforation site, and conditions

determinant in the strategy and material used in the surgi-

the surrounding dentin.133–137 However, the solution must

cal approach.144

not be propelled into perforation areas because this can

According to Gutmann and Harrison,106 certain aspects

often cause severe tissue damage and paresthesia.138–143

of the case must be considered before surgical treatment

Sodium hypochlorite should always be delivered passively,

can be initiated:

using pipette carriers or cotton pellets, or placed in the pulp

chamber and gently transported along the main canal us-

• The amount of remaining bone and any surrounding os-

ing hand files, avoiding penetration at the wound site. The

solution may also be delivered by inserting a small suction

• The overall periodontal status

cannula into the canal beyond the perforation and then

• The duration and size of the defect

placing the liquid in the chamber to be passively drawn

• The surgical accessibility

into the canal to beyond the defect. If the perforation does

• The soft tissue attachment level

not include the main canal, then NaOCl is gently brought

• The patient's oral hygiene and medical status

to the limit of the defect interface and frequently replen-

• The surgeon's soft tissue management expertise

ished until hemostasis is achieved.

CH 13 Removal of Posts

Fig 13-3 (a) Schematic of a cast post and core that requires removal

for endodontic retreatment. (b) A rotary instrument is used to reduce

the diameter of the core. (c) The core is further reduced with a

Gonon bur. (d) The core is threaded with a Gonon trephine bur.

(e) A mandrel with a washer and cushions in place is threaded on

the post, and then the knurled knob is turned to remove the post.

(Courtesy of Dr Nadim Z. Baba, Loma Linda, CA.)

31-mm-long Endodontic

Cariesectomy Bur

Endodontic Shallow

shaft (0.7 mm) on the

#1/4, #1/2, & #1

Fig 13-4 Gonon post puller device.

Fig 13-5 Munce Discovery Burs (CJM Engineering).

Mechanical Devices

Fig 13-6 (a) Radiograph of a maxillary right lateral incisor with an apical lesion requiring the

removal of a cast post and core and endodontic retreatment. (b) The cast post and core is

isolated with rubber dam. (c) The cast post and core is shaped into a roughly cylindric shape. (d)

A Munce Discovery Shallow Troughers (CJM Engineering) is used to remove the cement around

the post. (e) A special bur is used to thread the head of the cast post and core. (f) Application

of counterclockwise rotational force using the wrench. (g) Gonon post in place and ready to be

used. (h) The screw is turned to open the jaws and create an extraction force. (i) Removal of post

and preservation of the tooth structure. (j) Postoperative radiograph showing the endodontically

retreated root canal and the definitive restoration. (Courtesy of Dr Marga Ree, Amsterdam.)

post to protect the tooth from the lifting action of the pliers

(Fig 13-6). Should the post be successfully removed at this

point, the retreatment of the tooth may proceed following

inspection of the root to verify its integrity.

The Gonon post removal system is less invasive then the

Masserann Kit and the LGPP and requires less removal of

tooth structure.11,38

Page numbers followed by "f" indicate fig-

ures; those followed by "t" indicate tables; Bacteria, 24f, 139

cast post and core, 80–82, 80f–82f

those followed by "b" indicate boxes

Balanced forces technique, 195

ferrule effect on, 84

Base metal alloy, 36

fiber-reinforced resin post, 82–83, 83f

intraradicular disinfection, 78, 78b

Abutment teeth, 4

description of, 127, 169

Acrylic resin provisional restorations, 84–85

implant placement and, 124f

post surface treatment, 79

Aluminum oxide, 79

orthodontic forced eruption and, 116,

provisional restorations, 86–87

Alveolar ridge, 123, 150–152

radicular dentin, 78–79

Amalgam cores, 48–50, 49f–50f

surgical crown lengthening and, 108–109

Amalgam restorations

tooth fracture effects on, 111f

techniques of, 78–84, 80f–83f

complete-crown restoration versus, 6

treatment modalities for maintaining,

voids created during, 79, 79f

discoloration caused by, 92

mercury release from, after tooth bleaching, Bis-acryl composite resin, 85

Cervical root resorption

Bite test, 24, 24f

intracoronal tooth bleaching as cause of,

Amelogenesis imperfecta, 93

Bleaching. See Tooth bleaching.

Bond strength, extracoronal bleaching effects

invasive, 29f, 29–30

Ankylosis-related root resorption, 28f, 29,

Cervical tooth structure, for ferrule, 68–69

Broken instruments

Chairside extracoronal bleaching, 100

Anterior teeth. See also specific teeth.

illustration of, 196f

Combined endodontic-periodontal

anchorage for, 118

prevalence of, 196

conditions, 26–27

endodontically treated

removal of, 181, 196–199

Complete-crown restoration, 6

complete coronal coverage in, 7

Complex amalgam restorations, 6

description of, 6–7

Composite resin cores, 51–52

restorations for, 8, 34–35

Calcium hydroxide-containing sealer, 77–78

Composite resin restorations

discoloration caused by, 92

Apical lesions, 20

Carbamide peroxide, 94–95

endodontically treated teeth, 5–6

Apical perforations, 169, 173

Carbon fiber–reinforced epoxy resin posts,

fracture resistance of, 35

Apical seal, 10, 63, 67

41–43, 41f–43f, 42t

At-home extracoronal bleaching, 100, 102

Cast posts and cores. See Custom cast posts

time until failure with, 5–6

Computer-aided design/computer-assisted

antibiotics use in, 139

definition of, 137

glass-ionomer, 76b, 76–77

Cone beam computed tomography, 141

dietary considerations, 139

polycarboxylate, 76

Core ferrules, 68

examples of, 137–138, 138f

post type and, 76b, 77

Cores. See Posts and cores.

general principles of, 139–141

properties of, 75, 76b–77b

Coronal teeth preparation, 66

molars, 141f–142f, 141–143

resin, 77, 79, 82–84

Coronal-coverage crowns

premolars, 143f, 143–144

resin-modified glass-ionomer, 77

anterior teeth, endodontically treated, 34

prognosis after, 140–141

ultrasonic post removal affected by, 191

posterior teeth, endodontically treated, 34

root resorption concerns, 139–140, 140f

zinc phosphate, 76, 76b

Cracked teeth, 22–26

Avulsed tooth, 138f, 144, 145f

Craze lines, 22–23, 23f, 70, 70f

Crestal perforations, 169, 171, 173, 174f

cuspal deflection of, 7–8

for orthodontic tooth movement, 121

flexibility of, 7

Forced eruption, orthodontic. See

crown-root ratio, 116–117, 124

fracture of, 4–5

Orthodontic forced eruption.

See also Orthodontic extrusion.

length of, post length correlation with,

moisture content in, 7, 35

root. See Root fracture.

prosthetic. See Prosthetic crown.

physical properties of, 7–8

tooth. See Tooth fractures.

Crown lengthening, surgical. See Surgical

posterior teeth. See Posterior teeth.

Free radicals, 95, 100

crown lengthening.

posts and cores effect on, 36

Furcation perforations, 169, 173

Crown-root fractures

proprioception of, 8

diagnosis of, 128

prosthetic crown, 201–205, 203f–204f

incidence of, 132

provisional restorations in, 87

Gates Glidden instruments, 11, 64

proximal contact of, 4

shear strength of, 8

augmentation of, 123

sound tooth structure, 14

excessive display of, 109f

Cuspal deflection, 7–8

survival rates for, 4, 20

irritation of, from tooth bleaching, 101

Cuspal fracture odontalgia, 22

time until failure, 5–6

postrestorative recession of, 155f

Custom cast posts and cores

ultrasonic vibration effects on, 192

treatment planning for. See Treatment

Gingival connective tissue, 192

cementation of, 80–82, 80f–82f

Glass fiber–reinforced epoxy resin posts,

direct fabrication technique for, 37–38,

vital teeth versus, 4

43f, 43–45, 44t, 45f

Epoxy resin posts

indications for, 37

carbon fiber–reinforced, 41f–43f, 41–43

core buildup material use of, 52

indirect fabrication technique for, 38–41

glass fiber–reinforced, 43f, 43–45, 44t,

silver alloys added to, 52

lost-wax technique, 36, 37f

Glass-ionomer cement, 76b, 76–77, 191

for posterior teeth with divergent roots,

Extracoronal bleaching

resin-modified, 77

at-home, 100, 102

surface treatment of, 79

Gonon post removal system, 183, 184f

zinc phosphate cementation of, 80–82,

dental professionals' role in, 101–102

enamel effects of, 101

apical seal and, 10, 63, 67

gingival irritation secondary to, 101

condensation of, 67f

in-office, 99f, 99–100

immediate versus delayed removal of,

restorations and, 101

risks associated with, 100–102

instruments for removal of, 67

Dental fluorosis, 93–94

tooth sensitivity secondary to, 100–101

removal of, 66–67, 67f

craze lines in, 70

orthodontic. See Orthodontic extrusion.

surgical. See Intra-alveolar transplantation.

post diameter effects on, 64

Hereditary hypophosphatemia, 93

residual thickness of, 11, 70–71

H O . See Hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide, 94–96, 100–102

thickness of, 11, 70–71

intra-alveolar transplantation for improving,

Dentogingival junction, 108

Idiopathic root resorption, 30, 30f

restoration retention affected by, 68f,

Immediate implant placement. See

Osseointegrated implants, immediate

Direct core materials, 48–52

surgical crown lengthening consideration

placement of.

Discoloration of teeth. See Tooth

osseointegrated. See Osseointegrated

Distofacial root, 13

cementation of, 77, 82–83, 83f

description of, 14–15

biologic width considerations, 124

self-adhesive resin cement for, 82–83, 83f

complications of, 159–160

Eggler post removal, 186, 187f–188f

surface treatment of, 79

in growing patients, 124, 125f

immediate, 123. See also

decalcification of, 93

Osseointegrated implants, immediate

extracoronal bleaching effects on, 101

Fixed partial dentures

placement of.

hypocalcification of, 93

provisional, modification into matrix for

hypoplasia of, 93

amalgam core buildup, 49–50, 50f

nerve injuries during, 159–160

Enamel craze lines, 22–23, 23f

survival rates for, 4–5

orthodontic extrusion effects on, 124

Endodontically treated teeth

Flapless crown lengthening, 112

postextraction, 117, 118f

anterior teeth, 6–7

Incisors, 12–13

characteristics of, 7–8

for forced eruption, 118, 119f

Indirect fabrication, of custom cast posts and

endodontically treated

description of, 35

Occlusal forces, 6

Indirect provisional restorations, 85–86

provisional crown as matrix for amalgam

Orthodontic extraction, 123

Infection-related root resorption, 27–28,

core buildup in, 50, 51f

Orthodontic extrusion

crown-root ratio improvements through,

Infractions, 23–25

infraction risks, 23

In-office extracoronal bleaching, 99f,

root morphology of, 13

implant placement benefits of, 124

intra-alveolar transplantation advantages

Instrument Removal System, 199

Mandibular premolars

infraction risks, 23

mechanical application guidelines for,

broken. See Broken instruments.

post placement in, 14

diameter of, root fracture and perforation

root morphology of, 13

periodontal advantages of, 123

Masserann Kit, 185–186, 186f

success factors, 116

intra-alveolar transplantation, 129

Masserann Micro Kit, 196

Orthodontic forced eruption. See also

post space preparation using, 11, 64

Maxillary canines, 12

rotary. See Rotary instruments.

Maxillary first molars

advantages of, 125

Intentional replantation, 138, 138f, 176

post diameter excess in, 65

Interdentin cracks, 182

root morphology of, 12–13

application of, 118–121, 119t–120t

Internal resorption, 28, 28f

Maxillary first premolars

biologic width and, 116, 124f

Interproximal papillae, 124

post placement in, 14

biology of, 121–122

root morphology of, 12

brackets and wires for, 118, 120

adjunctive procedures, 128–129

two-rooted, 12, 14

coronal restoration goals of, 116–117

advantages of, 132

Maxillary incisors

crown fracture and, 116

case report of, 129, 130f–131f

endodontically treated

esthetics of, 123

complications of, 132–133

canal filling material in access cavity of,

contraindications for, 132

goals of, 116–117

disadvantages of, 132

with natural crowns, 35

guidelines for, 120t

esthetics affected by, 132

forced eruption of, 120f

indications for, 116

ferrule effect improved through, 132

post placement in, 14

maxillary incisors, 120f

fixation after, 131

root morphology of, 12

mechanics of, 118–120, 119f–120f,

histologic evaluation of outcome of,

infraction risks, 23

modalities of, 119t

palatal roots in, 71, 71f

orthodontic considerations, 123

indications for, 132

root morphology of, 12–13

instruments used in, 129

periodontal considerations, 123, 123f

outcomes of, 131–133

Maxillary premolars

principles of, 118, 119f

periodontal healing after, 131

endodontically treated, 35

progression of, 115–116

prognosis after, 133

infraction risks, 23

surgical technique of, 128–129

root morphology of, 12

research considerations, 124–125

Intracoronal tooth bleaching, 96–99,

scope of, 123–125

Intrapulpal hemorrhage, 92, 93f

Mesio-occlusal restorations, 6

Intraradicular disinfection, 78, 78b

Orthodontic tooth movement, 121, 123

Intrusive luxation, 132

Mineral trioxide aggregate, 171–173, 172f

Orthodontic wire, 39f

Irreversible pulpitis, 20, 24

Moisture content, 7, 35

Orthopedic force, 118

Orthopedic implant site preservation or

autotransplantation of, 137, 141f–142f,

Lasers, for crown lengthening, 112

Osseointegrated implants

Little Giant Post Puller, 183, 183f

advantages of, 149

Loosening of posts, 9–10, 15

infraction risks, 23

buccolingual positioning of, 157f

Lost-wax technique, 36, 37f

mandibular. See Mandibular molars.

complications of, 159–160

Luting agents, 75–77. See also Cement.

maxillary. See Maxillary molars.

coronoapical positioning of, 157f

perforation of, 172f, 174f–175f

description of, 125

post and core placement in, 71

immediate placement of

Mandibular canines, 13–14

Mottled tooth, 93–94

advantages of, 155

Mandibular fractures, 160

alveolar wall gap effects on, 158

Mandibular incisors

Mucoperiosteal flap, 153

contraindications for, 155–156

endodontically treated

Multiple idiopathic root resorption, 30, 30f

definition of, 154

with natural crowns, 36

dehiscence effects on, 158–159

post avoidance in, 14

factors that affect, 156–159

root morphology of, 13

Nickel-titanium files, 195–196

fenestration effects on, 158–159

Mandibular molars

indications for, 155–156

distal roots in, 71, 71f

periapical pathosis effects on, 159

primary stability during, 158

timing of repair, 168–169

tooth fracture secondary to, 182

scientific validation for, 154–155

tooth retention affected by, 167–168

ultrasonic devices for, 190–192

surgical protocols, 156

Periapical pathosis, 159

tooth position effects on, 156

Periodontal disease, 26, 124

instruments used to create, 11, 64

tridimensional position effects on, 156–

Periodontal ligament, 121, 139, 143–144

root fracture risks, 13

Periradicular lesions, 27

Post space preparation

mesiodistal positioning of, 157f

Peritubular dentin, 35

definitive restoration placement after,

Peroxides, for tooth bleaching, 94–96

contraindications, 152

Pivot crowns, 33–34

gutta-percha removal and, 66–67

description of, 149–150

PMMA. See Polymethyl methacrylate.

provisional restoration placement after, 88f

in healed sites, 152–154, 153f–154f

Polycarboxylate cement, 76

root perforation caused during, 27f, 170

immediate loading of, 154

Polyethylene fiber–reinforced posts, 45f,

immediate provisionalization, 153–154

amalgam, 48–50, 49f–50f

indications for, 152

carbon fiber–reinforced epoxy resin, 41–

nonsubmerged technique, 153

acrylic resin provisional restorations, 84

scientific validation for, 152

eugenol effects on, 78

complications of, 9–14

submerged technique, 153

shrinkage during, 51

composite resin, 51–52

Osseointegration, 152

Polymethyl methacrylate, 84–86

custom cast. See Custom cast posts and

cementation of. See Cement; Cementation.

description of, 41

Palatal canal, 71f

depth of, 11–12

direct materials, 48–52

Passive eruption, 108, 109f

diameter of, 11, 64, 65f

for endodontic treatment of tooth under a

fiber. See Fiber posts.

glass fiber–reinforced epoxy resin, 43f,

classification of, 170, 170b

guidelines for, 9

43–45, 44t, 45f

combined endodontic-periodontal

laboratory data findings regarding, 8–9

glass ionomer, 52

conditions caused by, 27

length of. See Post length.

in molars, 71, 71f

crestal, 169, 171, 173, 174f

loosening of, 9–10, 15, 191

in multirooted teeth, 71, 71f

definition of, 167

materials for, 14–15

polyethylene fiber–reinforced posts, 45f,

description of, 9

diagnosis of, 168–170

misconceptions about, 8

prefabricated. See Prefabricated posts.

prefabricated, 14

factors that affect, 10–13

provisional, 87–88

removal of. See Post removal.

furcation, 169, 173

purpose of, 35–36

retrofitting of, to existing crown, 207–211

hemorrhage at site of, 175

removal of. See Post removal.

tooth strengthening benefits of, 36

retrofitting of, to existing crown, 207–211

types of, 36–52

illustration of, 27f

sealer effect on retention of, 77–78

zirconia, 46f, 46–47

instrument diameter and, 11

Posterior teeth. See also specific teeth.

intentional replantation for, 176

surface treatment of, 79

anchorage for, 118

endodontically treated

management of, 172–176

crown restoration of, 34

mineral trioxide aggregate for, 171–173,

crown length and, 62–63, 71

custom cast posts and cores for, 40–41

excessive, 62–63

restorations for, 8, 34–35

molars, 172f, 174f–175f

fiber posts, 14–15

survival rate of, 34

orthograde management of, 172–175

guidelines for, 63–64

Prefabricated posts

post length excess as cause of, 62, 63f

post loosening affected by, 10

cementation or bonding of, 47, 48f

post space preparation as cause of, 27f

retentive ability and, correlation between,

description of, 14

premolar, 168f–169f, 173f–174f

prevention of, 13–14, 170–171

root curvature effects on, 71

types of, 41–47

prognostic factors for, 168–170, 170b,

root fracture risks and, 11, 62–63

autotransplantation of, 143f, 143–144

pulpal floor, 168

infraction risks, 23

repair materials for, 171–172

endodontist referral for, 181

retrograde management of, 175f, 175–

factors that affect, 181

illustration of, 184f–185f

perforation of, 168f–169f, 173f–174f

risk factors for, 14

mechanical devices for, 182–188,

post and core placement in, 71

root fracture and, differentiation of, 64

two-rooted, 12, 14

signs and symptoms of, 168

post characteristics that affect, 181

Pressure-related root resorption, 29, 29f

risks associated with, 182

Primary roots, 64

subcrestal, 173–175, 174f

root fracture secondary to, 182

Proprioception, 8

supracrestal, 169, 171, 173

rotary instruments for, 188–190,

surgical management of, 175f, 175–176

access cavity through, 203, 204f

amalgam cores under, 49

endodontic treatment of tooth with, 201–

amalgam. See Amalgam restorations.

anterior teeth, 8, 34–35

maxillary, 12–13

posterior teeth, 34

composite resin. See Composite resin

Root perforations. See Perforations.

retrofitting of post to, 207–211

Root resorption, 27–30, 139–140, 140f,

sound tooth structure amount necessary for,

extracoronal bleaching effects on, 101

factors that affect

Root surface conditioning agents, 176

time until failure with, 5–6

anatomical and structural, 70–71

Rotary instruments

Provisional fixed partial dentures, 49–50,

craze lines, 70, 70f

broken, 199f. See also Broken instruments.

dentin thickness, 11, 70–71

description of, 66

Provisional restorations

ferrule effect, 68f, 68–69, 84

post removal using, 188–190, 189f–191f

acrylic resin, 84–85

post diameter, 64, 65f

cementation of, 86–87

post length, 61–64, 62f–64f, 84

characteristics of, 84, 85b

provisional restorations, 67–68, 68f

composite resin, 85

root canal preparation, 66–68

immediate versus delayed removal of, 67

computer-aided design/computer-assisted

posterior teeth, 8, 34–35

post retention affected by, 77–78

manufacture of, 86

provisional. See Provisional restorations.

Setting shrinkage, 51–52

coronal access, 67–68

selection guidelines for, 8

Shear strength, 8

in endodontically treated teeth, 87

Retrofitting of post to existing crown, 207–

Shrinkage, 51–52

fabrication of, 85–86, 86b, 86f

Silver alloys, added to glass ionomer, 52

indirect, 85–86

Reversible pulpitis, 20, 21f, 24

Silver-palladium alloy, 36

luting of, 86–87

Single-tooth implants

materials for, 84–85

crown-root ratio, 116–117, 124

contraindications, 152

description of, 149–150

post and core, 87–88

perforation of. See Perforations.

in healed sites, 152–154, 153f–154f

surgical crown lengthening and, 111

immediate loading of, 154

Proximal contact, 4

Root canal preparation, 66–68

immediate provisionalization, 153–154

indications for, 152

instruments used to increase, 47

nonsubmerged technique, 153

overenlargement of, 13

scientific validation for, 152

Root canal system

submerged technique, 153

Pulpal disease, 26, 26f

broken instruments in. See Broken

Pulpal necrosis, 26f, 92, 93f, 128

Sodium hypochlorite, 78

Pulpitis, 20, 21f, 24

description of, 22, 22f

Sodium perborate, 94

Pulpless teeth. See Endodontically treated

smear layer created during cleaning and

Soft tissue crown lengthening, 110

Sound tooth structure, 14

Root canal therapy. See also Endodontically

S.S. White Post Extractor, 183

treated teeth.

Structural tooth defects, 93–94

Radicular dentin, 78–79

anatomical considerations, 21–22

Subcrestal perforations, 173–175, 174f

Radicular invaginations/grooves, 27

factors that affect, 20

Subgingival fractures, 4, 128

inadequately performed, 20f

Supracrestal perforations, 169, 171, 173

antibiotics use in, 139

Surgical crown lengthening

of avulsed tooth, 138, 138f, 144, 145f

root canal preparation for, 21–22

in anterior areas, 108, 109f

dietary considerations, 139

survival rates for, 20

biologic width considerations, 108–109

extraction and, 145–147, 146f

treatment planning for. See Treatment

description of, 69, 107

general principles of, 139–141

esthetic concerns, 108, 109f, 112

intentional, 138, 138f, 176

vertical root fractures versus, 25

factors that affect, 110

prognosis after, 140–141

ferrule considerations, 109–110

root resorption concerns, 139–140, 140f

crown fracture and. See Crown-root

Research, 124–125

Resin bonding, 78–79

factors that affect, 10–13

indications for, 107, 110, 111f

glass fiber–reinforced epoxy resin posts

description of, 77, 79

provisional restorations used with, 111

fiber-reinforced resin post cementation

instrument diameter and, 11

recommendations for, 112–113

using, 82–83, 83f

orthodontic extrusion contraindications,

restorative procedures after, 111

indications for, 84

ultrasonic post removal affected by, 191

post diameter and, 11, 65

in subgingival preparation margins, 110,

Resin-based sealer, 77–78

post removal as cause of, 182

Resin-modified glass-ionomer cement, 77

prevention of, 13–14

technique of, 110–112, 111f

residual dentin thickness effects on, 11

root perforation and, differentiation of, 64

endodontically treated teeth, 4

root. See Root resorption.

threaded posts as risk factor for, 10

fixed partial dentures, 4–5

vertical, 25–26, 26f

pulpal status assessments, 20, 21f

Tetracycline-related tooth stains, 92–93, 93f

events after, 150–151

Tetragonal zirconium polycrystals, 46

healing after, 150f

tooth fractures, 22–26

Thermocatalytic method, for intracoronal

implant replacement after, 117, 118f

vertical root fractures, 25–26, 26f

tooth bleaching, 98

Threaded posts, 9–10

replantation and, 145–147, 146f

Tissue engineering, 123

resorption after, 151

Ultrasonic devices, for post removal, 190–

ridge preservation after, 150–152

autotransplantation for. See

socket defects, 158–159, 159f

Ultrasonic tips, 198–199

for vertical root fracture, 25–26

Ultraviolet photo-oxidation technique, for

description of, 137

intracoronal tooth bleaching, 98

Tooth avulsion, 138f

biologic width affected by, 111f

Urea hydrogen peroxide, 94

in endodontically treated teeth, 4–5

Urethane dimethacrylate, 85

carbamide peroxide for, 94–95

post removal as cause of, 182

definition of, 93

types of, 22–26

extracoronal. See Extracoronal bleaching.

Vertical root fractures, 25–26, 26f

causes of, 5, 137

Vital teeth, endodontically treated teeth

hydrogen peroxide for, 94–96, 100–102

data analysis of, 5

intracoronal, 96–99, 97f–99f

fracture-related, 5

outcome of, 101–102

Tooth movement, orthodontic, 121, 123

over-the-counter products for, 94, 100

Tooth sensitivity, 100–101

Walking bleach, 96–98, 97f

peroxides for, 94–96

Tooth stains, 92–94

residual oxygen produced during, 99

Tooth stiffness, 35

sodium perborate for, 94

Tooth structure loss, 116

Yttrium-stabilized tetragonal polycrystalline

Tooth whitening, 93. See also Tooth

Tooth discoloration

aging-related, 92

calcific metamorphosis, 92

Transplantation. See Autotransplantation;

Zinc oxide–eugenol-based sealer, 77–78

diseases that cause, 93

Intra-alveolar transplantation;

Zinc phosphate cement

extrinsic causes of, 92

cast post and core cementation using,

intrapulpal hemorrhage, 92, 93f

Transportation of the canal, 22

80–82, 80f–82f

intrinsic causes of, 92–94

Trauma-related root resorption, 27

description of, 76, 76b

pulpal necrosis, 92, 93f

Treatment planning

provisional restoration cementation using,

structural tooth defects that cause, 93–94

combined endodontic-periodontal

tetracycline-related, 92–93, 93f

problems, 26–27

ultrasonic post removal affected by, 191

cracked teeth, 22–26

Zirconia posts, 46f, 46–47

forced. See Orthodontic forced eruption.

enamel craze lines, 22–23, 23f

normal process of, 121

infractions, 23–25

Source: http://www.dentalbooks.bg/PDF-2015/contemporary-restorations-Baba.pdf

The Gender Politics of Criminal Insanity: "Order-in-Council" Women in British Columbia, 1888–1950 DOROTHY E. CHUNN* Between 1888 and 1950, 38 women were confined for indeterminate periods toBritish Columbia's psychiatric system under executive "Orders-in-Council".Enlisting clinical, organizational, and government records, the authors explore thepsychiatric practices of control through which a male medico-legal establishmentstrove to comprehend and discipline these "criminally insane" women. Theauthoritative discourses and activities that shaped these women's forensic careersreflected a gendered conception of social order that was hegemonic during thisperiod. Such discourses helped to fashion the images of women, crime, and madnessthat continue to permeate public and official culture.

Le coût du hadj sera annoncé la semaine prochaine Lire en page 3 N° 5152 - MERCREDI 22 AVRIL 2015 QUALIFIÉE DE MASCARADEPAR LES PROCHES DU CHEIKH La statue de Benbadis«évacuée» du centre Lire en page 7 Enlèvement de la marchandise prohibée du port sec Anisfer de Rouiba NEUF DOUANIERS SOUS MANDAT DE DÉPÔT Le juge d'instruction de la deuxième chambre près le tribunal de Sidi-M'hamed (Alger), a ordonné hier, la mise en détention préventive de