Levitra enthält Vardenafil, das eine kürzere Wirkdauer als Tadalafil hat, dafür aber schnell einsetzt. Männer, die diskret bestellen möchten, suchen häufig nach levitra kaufen ohne rezept. Dabei spielt die rechtliche Lage in der Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle.

Maternal risk factors for gastroschisis in canada

Maternal Risk Factors for Gastroschisis in Canada

Erik D. Skarsgard*1, Christopher Meaney2, Kate Bassil3, Mary Brindle4, Laura Arbour5,Rahim Moineddin2, and the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet)

Background: Gastroschisis is a congenital abdominal wall defect that occurs

confidence interval, 0.83–0.87; p < 0.0001), smoking (odds ratio, 2.86; 95%

in one per 2200 pregnancies. Birth defect surveillance in Canada has shown

confidence interval, 2.22–3.66; p < 0.0001), a history of pregestational or

that the prevalence of gastroschisis has increased threefold over the past 10

gestational diabetes (odds ratio, 2.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.42–5.5;

years. The purpose of this study was to compare maternal exposures data

p 5 0.0031), and use of medication to treat depression (odds ratio, 4.4; 95%

from a national gastroschisis registry with pregnancy exposures from vital

confidence interval, 1.38–11.8; p 5 0.011) emerged as significant

statistics to understand maternal risk factor associations with the occurrence

associations with gastroschisis pregnancies. Conclusion: Gastroschisis in

of gastroschisis. Methods: Using common definitions, pregnancy cohorts were

Canada is associated with maternal risk factors, some of which are

developed from two databases. The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

modifiable. Further studies into sociodemographic birth defect risk are

database, a population-based dataset was used to record maternal exposures

necessary to allow targeted improvements in perinatal health service delivery

for women who experienced a gastroschisis pregnancy, while a

and health policy.

contemporaneous, geographically cross-sectional "control" cohort of pregnant

women and their exposures was developed from Canadian Community Health

Birth Defects Research (Part A) 103:111–118, 2015.

Survey data. Groups comparison of maternal risk factors was performed using

C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

univariate and multivariate logistic generalized estimating equation techniques.

Results: A total of 692 gastroschisis pregnancies (from Canadian Pediatric

Key words: gastroschisis; population-based registry; maternal risk factors;

Surgery Network) and 4708 pregnancies from Canadian Community Health

maternal age; teratogenesis

Survey were compared. Younger maternal age (odds ratio, 0.85; 95%

The Public Health Agency of Canada has documented a

Gastroschisis (GS) is a congenital abdominal wall defect

threefold rise in prevalence of GS over the last 10 years,

which results in the extrusion of the developing fetal intes-

to approximately 1 per 2200 births (Moore et al., 2013). A

tines into the amniotic space. It is usually detected prena-

similarly observed increase in GS prevalence has been

tally by maternal serum screening and ultrasound, and

made in many other countries, including the United States

tends to occur as an isolated congenital anomaly. When a

and several European nations (Laughon et al., 2003; Inter-national Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and

prenatal diagnosis of GS is made, arrangements are made

Research, 2009; Langlois et al., 2011), prompting referen-

for delivery at an obstetrical center that is functionally

ces to a "Gastroschisis Epidemic" (Kilby, 2006; Mastroia-

linked to a specialty pediatric hospital with the capability

covo et al., 2006; Keys et al., 2008). Epidemiologic studies

of providing surgical treatment after birth as well as essen-

of causation of GS have emerged from single state/region/

tial neonatal intensive care. Survival following birth of an

country birth defect registries, to pooled data from a net-

infant with GS exceeds 90%, however, survivors may

work of population-based congenital anomaly reporting

require prolonged hospitalization in high intensity nurs-

registries, all with an intent to better understand modifi-

eries, which makes them among the most expensive of con-

able risk factors for GS.

genital anomalies to treat (Sydorak et al., 2002; Skarsgard

Since 2006, the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

et al., 2008). The specific cause of GS remains unknown,

(CAPSNet) has collected standardized pre and postnatal

although the available evidence suggests interactions of

data on all cases of GS admitted to each of the 17 hospi-

multiple maternal risk factors lead to occurrence.

tals in Canada that provide specialty pediatric care forbirth defects. The collected data include maternal demo-graphic (age, home postal code) and exposures (e.g., smok-

1Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

ing, alcohol, recreational drug use) data for all GS

2Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto,

pregnancies. The purpose of this study was to explore the

association between maternal factors and GS in Canada by

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

4Department of Surgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

comparing maternal exposures data for GS cases identified

5Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver,

in CAPSNet with household exposures data for a geograph-

ically "cross-sectional" group of pregnant women from aCanadian Vital Statistics database.

This work was Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research(CIHR) Funding Reference # Sec 117139.

*Correspondence to: Erik D. Skarsgard, K0–110 ACB, 4480 Oak Street, Van-

Materials and Methods

couver, BC, V6H 3V4 Canada. E-mail:

[email protected]

The two primary data sources for this study consisted ofthe CAPSNet registry, and the Canadian Community Health

Published online 12 February 2015 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.

com). Doi: 10.1002/bdra.23349

Survey (CCHS, which is administered by Statistics Canada),

C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

a cross-sectional survey which collects information related

survey was conducted in alternate years). The CCHS sur-

to health status and health determinants of Canadians at

vey of 65,000 Canadians per year, targets persons aged 12

the household level, across all geographic regions (dissem-

years or older who are living in private dwellings in the

ination areas) in Canada (Canadian Community Health Sur-

ten provinces and the three territories. Persons living on

vey [CCHS], 2014). Through integration of data from these

Indian Reserves or Crown lands, clientele of institutions,

two sources, we were able to develop health and maternal

full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and res-

exposure risk profiles of mothers who gave birth to infants

idents of certain remote regions are excluded from this

with GS (from CAPSNet), to pregnant women sampled

survey. The sampling method ensures that all provinces'

from the CCHS. The variables that were consistently col-

health regions (provincially designated health service

lected across the two data sources include: history of alco-

areas) are sampled in proportion to the size of their

hol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and

heroin use during pregnancy, history of diabetes (type 1,

The CCHS covers approximately 98% of the Canadian

type 2, or gestational), use of depression medication dur-

population aged 12 or older, and collects information

ing pregnancy, and use of folic acid during pregnancy.

related to health status, health care usage, and healthdeterminants. These data can then be used to estimate, on

a health regional basis, potential relationships between

The CAPSNet consists of the 17 perinatal/surgical centers

health outcomes and economic, demographic, occupational,

that provide population-based pre- and postnatal care for

and environmental factors. Ultimately, the data are meant

GS in Canada (The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

to provide a better understanding of the health of Cana-

[CAPSNet], 2014). The CAPSNet registry was designed spe-

dians and inform public policy, through health surveillance

cifically for outcomes research and contains rigorously

and the facilitation of population health research.

defined fields that allow discrimination of risk variablesand treatment, as well as relevant clinical outcomes fromthe birth hospitalization to death or discharge. Data are

collected from maternal and infant charts by trained

This study used a cross-sectional design. In this design,

abstractors using a customized data entry program with

the GS (case) sample consisted of all mothers identified

built-in error checking and a standard manual of opera-

from the CAPSNet database between 2006 and 2012, who

tions and definitions. Abstracted prenatal information

had a GS pregnancy resulting in a live birth, stillbirth or

details maternal risk variables including demographics

termination of pregnancy, while the non-GS (control) sam-

(postal code of residence), prenatal exposures including

ple consisted of all pregnant mothers responding to the

smoking, alcohol, and a variety of nonprescription drugs;

CCHS surveys (Cycle 1.1 [2001], Cycle 2.1 [2003], Cycle

medical comorbidities, quantitative ultrasound and other

3.1 [2005], CCHS 2007, and CCHS 2010). Although CCHS

prenatal diagnostic data, and information on all pregnancy

data do not differentiate women whose pregnancy was or

All data collection

was not complicated by GS (or any other birth defect), it

"observational" and is not used to influence the care of

is assumed that the CCHS cohort represents a reasonable

any individual patient.

control group because the sample is large and the overall

Data from each CAPSNet center are de-identified and

birth defect rate is known to be rare, and because controls

transmitted electronically to a centralized repository for

misclassification causes bias toward the null for the risk

cleaning, quality assurance and storage. Thereafter, the

aggregate dataset is overseen by a research coordinator

The comparison variables of interest between cases

and controls are summarized in Table 1. Definitions of

steering committee comprised of pediatric surgeons, neo-

"exposure" in both databases included any use, on at least

natologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, and an epi-

one occasion of the listed substances, during a time when

demiologist. Aggregate data use for research purposes is

the woman was pregnant, whether known or unknown

enabled by inter-institutional data sharing agreements,

(Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network, 2013). A coincident

and requires that each CAPSNet center maintain institu-

history of diabetes, could mean that the woman had pre-

tional review board approval for data collection. Aggregate

existing diabetes (type 1 or 2) diagnosed by a health pro-

data release requires project-specific institutional review

fessional or had gestational diabetes requiring medication

board approval from the principal investigator's institu-

or dietary modification. A history of depression requiring

tion, and complies with Health Information Portability and

medication meant that the woman had a mood disorder

Accountability Act (HIPPA) requirements.

diagnosed by a health professional and received anti-depressive medication at any time in CAPSNet, (or within

past month for CCHS), for any duration during her preg-

CCHS is a cross-sectional household survey administered

nancy. Folic acid use meant that the woman used a multi-

by Statistics Canada on an annual basis (before 2007 the

vitamin containing folic acid before or upon realization of

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111–118 (2015)

TABLE 1. CCHS and CAPSNet Variables Definitions

CAPSNet data definitionsa

Did you drink any alcohol during your last

Record if any alcohol use during pregnancy

Cigarette smoking

Did you smoke during your last pregnancy?b

Record if cigarettes were smoked during this preg-

nancy. If unknown or if no cigarettes were

During your last pregnancy, did you smoke daily,

smoked during pregnancy, leave the box

occasionally or not at all?c

1 Daily 2 Occasionally 3 Not at all

Have you used marijuana in the past 12 months?

Record whether or not the mother used any of the

following during this pregnancy.

Have you used cocaine or crack in the past 12

Methamphetamine or crystal meth

Have you used speed (amphetamines) in the past 12

Heroin: includes methadone

Have you used heroin in the past 12 months?

Do you have diabetes?

Record the mother's status as a diabetic during this

Pre-existing DM diagnosed prior to conception

Gestational diabetes

In the past month, did you take anti-depressants

Record use of antidepressants during this preg-

such as Prozac, Paxil or Effexor?:

nancy: includes selective-serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRI) (i.e. Zoloft, Paxil or Prozac)

Did you take a vitamin supplement containing folic

Record whether the mother has been taking regular

acid before your pregnancy, that is, before you found

prenatal vitamins during this pregnancy.

out that you were pregnant?

None: no folic acid nor prenatal vitamins taken

before the start of the second trimester.

Folic acid: initiated prior to pregnancy or within the

first trimester.

Vitamins: initiated prior to pregnancy or within the

aFrom CAPSNet Abstractors' Manual vol 5.1.0, April 2013.

bQuestion from CCHS 1.1.

cQuestion from CCHS 2.1, 3.1, 2007, 2010.

her pregnancy. Age was estimated from maternal date of

residence was assigned using dissemination area (DA), a

birth, as reported through both datasets, and was analyzed

small, relatively stable geographic unit composed of one or

as a continuous variable. Geographic location of home

more adjacent dissemination blocks. It is the smallest

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

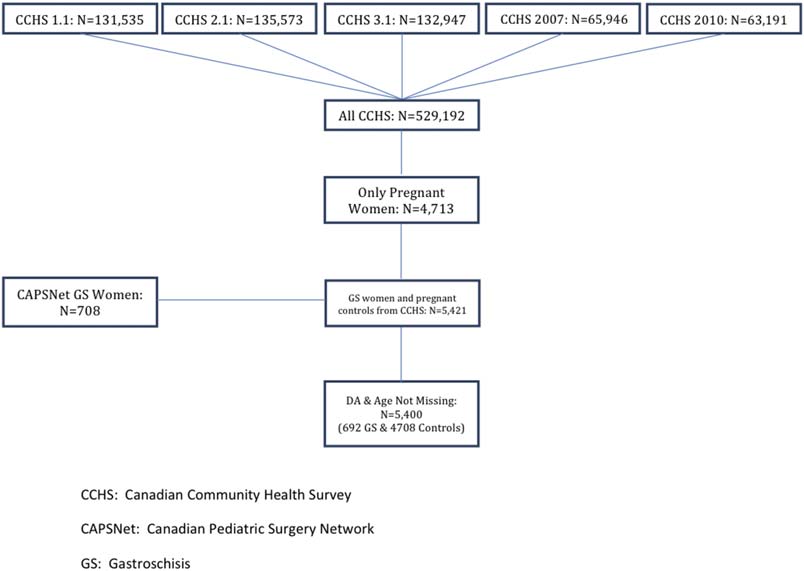

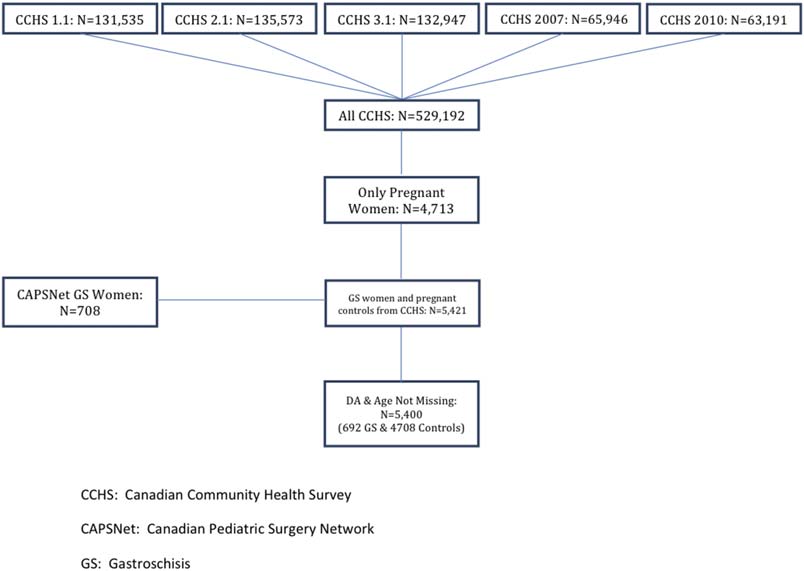

FIGURE 1. Inclusion/exclusion flow diagram of patients

analyzed in this study.Patients were collected from

five cycles of the CCHS (1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 2007 and

2010). Patients who were pregnant during the time of

the survey were included. The CAPSNet registry was

used to identify women who had gastroschisis preg-

nancies between 2006 and 2012, and those with

complete data were included.

standard geographic area for which all census data are

cies (from CAPSNet) and 4708 "control" pregnancies from

disseminated within Canada, and can be assigned using

the Postal Code Conversion File software (Wilkins and

The 692 GS mothers came from a total of 465 DAs and

Khan, 2010).

the 4708 control mothers came from a total of 1285 DAs.

Initially, we intended to perform a 1:1 matched case

The mean age of the GS mothers was significantly lower

control study where mothers were matched on age (a

than that of the controls (23.64 years; SD 5 4.79 years vs.

known GS risk factor) and DA, which would have allowed

28.84 years; SD 5 6.11 years; p < 0.0001). When maternal

us to control for some predisposing environmental factors.

age was interrogated as a predictive variable using bivari-

When analysis was completed under the proposed design

ate and multivariate generalized estimating equation mod-

many associations between categorical risk factors and

independently predictive

outcome of a GS pregnancy had low counts in some cells

occurrence of a GS pregnancy (odds ratio [OR], 0.85; 95%

of the contingency tables. As a result, these data could not

confidence interval [CI], 0.83–0.87; p < 0.0001).

be released from Statistics Canada due to anonymity con-

The relationships between maternal risk factors during

cerns and an alternative design was necessary.

pregnancy and the occurrence of GS are summarized inTables 2 and 3. Table 2 displays 2x2 tables, estimated

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values associ-

To avoid issues related to low cell counts, we chose not to

ated with a variety of maternal substance exposures dur-

match based on any demographic variables a priori. Rather

ing pregnancy, folic acid use, depression medication use or

we treated GS mothers and CCHS controls as being

a history of diabetes. Due to low cell counts, exposures

"clustered" within DAs and used logistic generalized esti-

data for cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine were sup-

mating equation methods to account for this design fea-

pressed, and so an aggregate variable (any illicit drug use

ture. Moreover, we treated maternal age, (a known risk

inclusive of marijuana) was created. Table 2 suggests that

factor for GS occurrence) as a covariate in each model and

exposure to alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, illicit drugs or

estimated the adjusted odds of a GS birth, as a function of

medication for depression during pregnancy, as well as a

other hypothesized maternal risk factors after controlling

history of diabetes increases the likelihood of a GS preg-

for age. Where sample size allows we have summarized

nancy. Conversely, the use of folic acid appears to be pro-

the association between maternal factors (all categorical

tective against a GS pregnancy.

variables) and GS occurrence using contingency tables.

Given the awareness of young maternal age as a risk

factor for GS, age adjustment was performed in the logisticgeneralized estimating equation risk modeling, as summar-

ized in Table 3. After adjustment for maternal age, the

The process of deriving the case (GS pregnancies from

association between maternal exposures to cocaine and

CAPSNet) and control (non-GS pregnancies from CCHS)

marijuana individually, (and illicit drugs collectively) and

maternal cohorts is illustrated in Figure 1. After exclusions

the occurrence of GS persists. In the multivariate model,

for incomplete data there were a total of 692 GS pregnan-

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111–118 (2015)

(OR, 3.54; 95% CI, 2.22–5.63; p < 0.0001), and use of med-

TABLE 2. 2 x 2 Contingency Tables with Odds Ratios, 95% Confidence Inter-

ication to treat depression (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.38–11.8;

vals, and p-Values Describing the Relationship between the Association

between Maternal Risk Factors and the Occurrence of a Gastroschisis

DiscussionGastroschisis is among the most common structural birth

defects, and its cause remains unknown. The phenomenon

of increased prevalence has been observed in several juris-

583 (92.98) 4454 (95.64)

dictions, and continues to be a stimulus for epidemiologic

evaluation of risk factors, both maternal (physiological,teratogens, socioeconomic) and environmental (Torfs et al.,

231 (33.38) 610 (13.06) 3.34 2.79, 3.99 <0.0001

1994; Reefhuis and Honein, 2004; Rittler et al., 2007; Cas-

461 (66.62) 4061 (86.94)

tilla et al., 2008; Salemi et al., 2009; Waller et al., 2010;

Agopian et al., 2013).

8.03 5.63, 11.46 <0.0001

The most widely observed association in GS pregnancy

614 (88.73) 3477 (98.44)

occurrence is its inverse relationship with maternal age.

The risk seems to be highest in the teenage cohort. Aggre-

gate data from EUROCAT (a consortium of birth defect

registries which combines registry data from 23 countries)

report a relative risk of 7.0 in the under 20 age cohort,

and a RR of 2.4 in the 20 to 24 age cohort, compared withthe age 25 to 29 reference group (Reefhuis and Honein,

2004). While a strong association with maternal age is

certain, what is less clear is whether the increased preva-

lence of GS is due exclusively to an increased prevalence

within the teenage mother population, or to a GS preva-

lence increase across all maternal age strata (Kazauraet al., 2004; Loane et al., 2007). Regardless of the exact

nature of this association, the relationship between mater-

9.35 6.64, 13.15 <0.0001

nal age and GS should be factored in to all studies of GS

600 (86.71) 3475 (98.39)

epidemiology, with analyses of all putative risk factors

being subject to age-adjustment.

Several epidemiologic studies of causation suggest a

moderate risk of GS associated with smoking during preg-

672 (97.25) 4651 (98.81)

nancy (Haddow et al., 1993; Draper et al., 2008; Feldkamp

et al., 2008), and data from Canada identify a higher rate

4.65 2.61, 8.30 <0.0001

of smoking during pregnancy in mothers with GS (Wein-

670 (96.82) 3544 (99.30)

sheimer et al., 2008). Not only is there a maternal smokingassociation with GS prevalence, there is also an association

with clinical outcome, with GS infants of smoking mothers

134 (19.36) 1289 (27.83) 0.62 0.51, 0.76 <0.0001

having more severe bowel injury at birth (Weinsheimer

558 (80.64) 3342 (72.17)

et al., 2008; Brindle et al., 2012). In addition to smoking,

Empty cells, suppressed due to low counts.

illicit drug use is another purported risk factor for GS,with cocaine, marijuana, and methamphetamine observed

significant predictor of GS occurrence. Similarly, although

to have a significant age-adjusted association with GS

alcohol exposure remained predictive after age adjustment,

occurrence (Draper et al., 2008; Weinsheimer et al., 2008;

its predictive association with GS occurrence disappeared

Brindle et al., 2012).

with multivariate analysis. The other significant variable

The current study provides further insight into GS epi-

change associated with age-adjustment was the loss of the

demiology through integration of a contemporary, Cana-

apparent protection associated with folic acid use.

dian population-based GS dataset with Vital Statistics data

Younger maternal age, smoking (OR, 2.86; 95% CI,

from a cross-sectional, representative cohort of pregnant

2.22–3.66; p < 0.0001), a history of diabetes (OR, 2.81;

mothers from the Canadian Community Health Survey.

95% CI, 1.42–5.5; p 5 0.0031), history of illicit drug use

Critical to the accuracy and reliability of this dataset

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

TABLE 3. Bivariate, Age-Adjusted, and Multivariate Logistic Regression Models Evaluating Risk Factor Prediction of a Gastroschisis Pregnancy

Bivariate logistic gee model

Age-adjusted logistic GEE model

Multivariate logistic GEE model

—, not used in multivariate model, rather combined in composite "illicit drug" variable.

GEE, general estimating equation.

integration, is the accuracy of case and control ascertain-

for maternal age and race (Polen et al., 2013). Conversely,

ment, and equivalence of risk factor definitions. One of the

two other studies looking at associations between selective

limitations of birth defect registry ascertainment (for

serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy did not demon-

example EUROCAT) is the accuracy of discharge diagnosis

strate a significantly increased rate of common structural

abstraction from hospital charts. The diagnostic code for

birth defects among exposed infants (Alwan et al., 2007;

GS (International Classification of Disease, ICD-9 756.7) is

Louik et al., 2007). It is likely that an association between

shared with another congenital defect of the abdominal

depression and/or its treatment and the occurrence of GS

wall (omphalocele), which differs dramatically from GS

has many confounders, and, therefore, caution should be

and is frequently associated with genetic patterns of inher-

exercised in inferring a direct relationship in the absence

itance. The British Pediatric Association modification of

of other supportive studies.

ICD-9 is used by some registries, and allows differentiation

Our data identify a maternal history of pregestational

of gastrochisis from omphalocele, however it is not used

type 1 or type 2 or gestational diabetes mellitus as being

uniformly. The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAP-

independently predictive of a GS pregnancy. While a rela-

SNet) database, on the other hand, is a research database,

tionship between pregestational/gestational diabetes and

for which cases are ascertained by clinicians who are

increased rates of several birth defects (specifically, cardio-

directly involved in either prenatal diagnosis or postnatal

vascular defects), is well established, no specific associa-

treatment of GS, which improves diagnostic accuracy

tion with human GS has been reported previously.

Although the concept of abdominal wall malformations

Our study reinforces the inverse relationship between

associated with a hyperglycemic state is plausible and sup-

maternal age and GS occurrence, as well as associations

ported by observations of GS in pregnant rats who were

with maternal smoking and illicit drug use, which were

made diabetic by intraperitoneal streptozotocin (Padma-

both independently predictive of occurrence on multivari-

nabhan and al-Zuhair, 1987–1988), this relationship is

ate logistic regression modeling. Although it was observed

intuitively at odds with the observed protective effect of

to be protective on univariate analysis, use of folic acid

overweight or obese prepregnancy BMI on the risk of hav-

lost its predictive effect following adustment for maternal

ing a GS pregnancy (Lam et al., 1999; Waller et al., 2007;

age. We also observed that treatment of depression with

Stothard et al., 2009). A potential explanation for our find-

any anti-depressive medication was associated with an

ings is an underreporting of gestational diabetes in the

increased risk of GS (OR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.38 5 11.8). A

CCHS cohort. A population-based study of rates of bio-

recent report from the National Birth Defects Prevention

chemically validated gestational diabetes in the province

Study using a case control methodology, looked at the

of Ontario, showed a doubling of age-adjusted rate from

effect of periconceptual use of the anti-depressant venla-

2.7 to 5.6% between 1996 and 2010 (Feig et al., 2014),

faxine on the occurrence of birth defects, and observed a

which is substantially higher than the rate of 1.2%

statistically significant association with GS, after adjusting

observed in our CCHS cohort, and suggests the possibility

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111–118 (2015)

that a diagnosis of gestational diabetes was unknown to

many pregnant women at the time they were surveyed.

The authors thank Alison Butler, CAPSNet coordinator, for

We are reluctant to ascribe much significance to this

her administrative efforts in support of this work

observation, other than to note its statistical significance,and suggest that future studies of GS epidemiology should

evaluate this potential association further.

Agopian AJ, Langlois PH, Cai Y, et al. 2013. Maternal residential

While this study has some unique strengths, it also has

atrazine exposure and gastroschisis by maternal age. Matern

limitations. Combining unrelated sources of data (despite

Child Health J 17:1768–1775.

common definitions) for cases and controls raises concernover the comparability of maternal exposures between

Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. 2007. Use of selective

groups. Both data sources reflect self-reporting and are,

serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth

therefore, subject to recall bias, and potentially, a reluc-

defects. N Engl J Med 356:2684–2692.

tance to admit to risky behavior during pregnancy. Neither

Brindle ME, Flageole H, Wales PW, et al. 2012. Influence of

source specifically identifies pre or peri-conceptual expo-

maternal factors on health outcomes in gastroschisis: a Canadian

sure from exposure during pregnancy. The inquiry around

population-based study. Neonatology 102:45–52.

timing of exposure in the CCHS database is variable, rang-ing from "past month" (antidepressant use), "during preg-

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). 2014. Available at:

nancy" (alcohol, smoking), or "past 12 months" (illicit

5Accessed August 29, 2014.

drugs, which could capture exposures before pregnancy).

As previously acknowledged, the occurrence of birth

Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network. 2013. CAPSNet Data

defects, including GS within the "control" CCHS cohort can-

Abstractors Manual. V 5.1.0. Available at:

not be excluded, yet we contend that it represents a rea-

Accessed August 29, 2014.

sonable control sample based on its size and the low birthdefect rate.

Castilla EE, Mastroiacovo P, Orioli IM. 2008. Gastroschisis: inter-

Finally, the time periods reflected by the two databases

national epidemiology and public health perspectives. Am J MedGenet C Semin Med Genet 148C:162–179.

are different: the CCHS controls represent an aggregatecohort from surveys done in 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, and

Draper ES, Rankin J, Tonks AM, et al. 2008. Recreational drug

2010, while the CAPSNet cases were accrued between

use: a major risk factor for gastroschisis? Am J Epidemiol 167:

2006 and 2012). Another limitation is the inability to con-

trol for geographic factors (location of maternal resi-dence). Although our initial intent was to undertake case/

Feig DS, Hwee J, Shah BR, et al. 2014. Trends in incidence of dia-

control matching by maternal age and dissemination area,

betes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: a large,population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 1996–2010. Diabetes

the low counts in many of the DA cells meant that these

data could not be released. We have, therefore, had toassume, for the purpose of this study, that GS occurs with

Feldkamp ML, Alder SC, Carey JC. 2008. A case control

the same prevalence across Canada, which we know is not

population-based study investigating smoking as a risk factor for

the case, based on spatial mapping analysis of GS cases

gastroschisis in Utah, 1997–2005. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol

across Canada (K. Bassil, personal communication, 2014).

We are also unable to make any observations of potential

Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Holman MS. 1993. Young maternal age

associations between maternal race and GS. In another

and smoking during pregnancy as risk factors for gastroschisis.

CAPSNet study of GS epidemiology, we have observed a

higher than expected prevalence of GS pregnancies in Abo-riginal women, although maternal ethnicity does not

International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and

emerge as independently predictive of occurrence (Brindle

Research. 2009. Annual Report 2009 with data for 2007. Rome, Italy:

et al., 2012). The fact that the CCHS excludes Canadians

International Center on Birth Defects. Available at: Accessed

living on Indian reserves means that Aboriginals may be

Month day, year.

underrepresented in our control group.

Future studies on causation of GS and other high

Kazaura MR, Lie RT, Irgens LM, et al. 2004. Increasing risk of

impact structural birth defects will be enabled by our abil-

gastroschisis in Norway: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am J Epi-

ity to integrate data from different sources, and speak to

the necessity of having access to and linkages for a varietyof clinical and administrative datasets. Improvements in

Keys C, Drewett M, Burge DM. 2008. Gastroschisis: the cost of anepidemic. J Pediatr Surg 43:654–657.

perinatal health service delivery and health policy repre-sent some of our greatest opportunities for outcome

Kilby MD. 2006. The incidence of gastroschisis. BMJ 332:250–

improvement for birth defects like GS.

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

Lam PK, Torfs CP, Brand RJ. 1999. A low pregnancy body mass

Rittler M, Castilla EE, Chambers C, et al. 2007. Risk for gastroschi-

index is a risk factor for an offspring with gastroschisis. Epidemi-

sis in primigravidity, length of sexual cohabitation, and change in

ology 10:717–721.

paternity. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 79:483–487.

Langlois PH, Marengo LK, Canfield MA. 2011. Time trends in the

Salemi JL, Pierre M, Tanner JP, et al. 2009. Maternal nativity as a

prevalence of birth defects in Texas 1999–2007: real or artifac-

risk factor for gastroschisis: a population-based study. Birth

tual? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 91:902–917.

Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 85:890–896.

Laughon M, Meyer R, Bose C, et al. 2003. Rising birth prevalence

Skarsgard ED, Claydon J, Bouchard S, et al. 2008. Canadian Pedi-

of gastroschisis. J Perinatol 23:291–293.

atric Surgical Network: a population-based pediatric surgery net-work and database for analyzing surgical birth defects. The first

Loane M, Dolk H, Bradbury I; EUROCAT Working Group. 2007.

100 cases of gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 43:30–34.

Increasing prevalence of gastroschisis in Europe 1980–2002: aphenomenon restricted to younger mothers? Paediatr Perinat

Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, et al. 2009. Maternal overweight

and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematicreview and meta-analysis. JAMA 301:636–650.

Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, et al. 2007. First-trimester use ofselective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth

Sydorak RM, Nijagal A, Sbragia L, et al. 2002. Gastroschisis: small

defects. N Engl J Med 356:2675–2683.

hole, big cost. J Pediatr Surg 37:669–672.

Mastroiacovo P, Lisi A, Castilla EE. 2006. The incidence of gastro-

The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet). 2014. Avail-

schisis: research urgently needs resources. BMJ 332:423–424.

able at: Accessed August 29, 2014.

Moore A, Rouleau J, Skarsgard ED. 2013. Chapter 7: Gastroschi-

Torfs CP, Velie EM, Oechsli FW, et al. 1994. A population-based

sis. In: Public Health Agency of Canada. Congenital anomalies in

study of gastroschisis: demographic, pregnancy, and lifestyle risk

Canada 2013: a perinatal health surveillance report. Ottawa, Can-

factors. Teratology 50:44–53.

ada: Public Health Agency of Canada. pp. 57–64. Available at:

Waller DK, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, et al. 2007. Prepregnancy

Accessed Month day, year.

obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med 161:745–750.

Padmanabhan R, al-Zuhair AG. 1987–1988. Congenital malfor-mations and intrauterine growth retardation in streptozotocin

Waller SA, Paul K, Peterson SE, et al. 2010. Agricultural-related

induced diabetes during gestation in the rat. Reprod Toxicol 1:

chemical exposures, season of conception, and risk of gastroschi-

sis in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202:241 e1–e6.

Polen KN, Rasmussen SA, Riehle-Colarusso T, et al. 2013. Associ-

Weinsheimer RL, Yanchar NL, Canadian Pediatric Surgical Net-

ation between reported venlafaxine use in early pregnancy and

work. 2008. Impact of maternal substance abuse and smoking

birth defects, national birth defects prevention study, 1997–

on children with gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 43:879–883.

2007. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 97:28–35.

Wilkins R, Khan S. Automated geographic coding based on the

statistics Canada postal code conversion files. Including postal

chromosomal birth defects, Atlanta — 1968–2000: teenager or

codes through October 2010. Available at:

thirty-something, who is at risk? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol

Accessed Month day, year.

Source: http://canadanews.ga/polopoly_fs/1.3010179!/httpFile/file.pdf

Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias -UNCPBA- Actualización sobre las bases terapéuticas para la Peritonitis Infecciosa Felina (PIF) y presentación de tres casos clínicos de PIF tratados con Talidomida. Alarcón, Gabriela Verónica; Paludi, Alejandro Esteban; Nejamkin, Pablo. Mayo, 2016

Carbamate and Pyrethroid Resistance in the Leafminer J. A. ROSENHEIM,' AND B. E. T ABASHNIK Department of Entomology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 J. Econ.Entomol.83(6): 2153-2158 (1990) ABSTRACT Populations of D1glyphus begini (Ashmead), a parasitoid of Lirlomyza leafminers, showed resistance to oxamyl, methomyl, fenvalerate, and permethrin in labo-ratory bioassays. Relative to a susceptible strain from California, maximum resistance ratiosfor these pesticides were 20, 21, 17, and 13, respectively. Three populations that had beentreated frequently with insecticides were significantly more resistant to all four insecticidescompared with an untreated Hawaii population and a California population with an unknownspray history. Parasitoids from a heavily sprayed tomato greenhouse on the island of Hawaiihad LC",'s for permethrin and fenvalerate that were 10 and 29 times higher than the fieldrate, respectively. Populations resistant to oxamyl and methomyl had LC",'s two- and sixfoldbelow the field rate, respectively. D. begini is one of the few parasitoids resistant to pyre-throids, with LC",'s exceeding field application rates. Resistant D. begini may be useful forcontrolling leafminers in management programs that integrate biological and chemical con-trols.