Levitra enthält Vardenafil, das eine kürzere Wirkdauer als Tadalafil hat, dafür aber schnell einsetzt. Männer, die diskret bestellen möchten, suchen häufig nach levitra kaufen ohne rezept. Dabei spielt die rechtliche Lage in der Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle.

Microsoft powerpoint - vajer.peter-smoking.cessation.ppt

Section 1: Burden of Disease

Tobacco Dependence, Attitudes

� Smoking is highly prevalent worldwide

and Treatment Strategies

� Smoking increases morbidity and mortality� The benefits of quitting have been

Department of Family Medicine

Semmelweis University

Gender-Specific Smoking

Smoking Prevalence of Adults vs

Prevalence Across the World

Youths: Young People Are Also at Risk

1.25 billion smokers worldwide1-2

*Young men/women = 15-year-old students who smoke cigarettes.

1. Shafey O, et al (eds). Tobacco Control Country Profiles 2003, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia, 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/globaldata/countryprofiles/en/. 2. Mackay J, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Second

1. Mackay J, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Second Ed. American Cancer Society Myriad Editions Limited, Atlanta,

Edition. American Cancer Society Myriad Editions Limited. Atlanta, Georgia, 2006. Also available online at:

Georgia, 2006. Also available online at: http://www.myriadeditions.com/statmap/.

Smoking: Leading Preventable

US Mortality From Smoking-Related

Cause of Disease and Death1

Top 3 Smoking-Attributable Causes of Death in US

#2 Ischemic heart disease

Lung (#1)* Leukemia

(AML, ALL, CLL)2-4

Pregnancy complications

Lung, Trachea, Bronchus Cancer †

Oral cavity/pharynx Laryngeal

Reduced fertility

Esophageal Stomach

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Ischemic Heart Disease †

Pancreatic Kidney

Respiratory Diseases

Cerebrovascular Disease

Ischemic heart disease (#2)*

Adverse surgical outcomes/wound healing

Stroke – Vascular dementia5

Peripheral vascular disease6

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Peptic ulcer disease†

COPD (#3)*Pneumonia

Poor asthma control

Approximately 438,000 annual US deaths attributable to cigarette smoking

*Top 3 smoking-attributable causes of death. †In patients who are Helicobacter pylori positive.

AML = Acute myeloid leukemia; ALL = acute lymphocytic leukemia; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia; COPD =

between 1997 and 2001

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SIDS = sudden infant death syndrome.

1. Surgeon General's Report. The Health Consequences of Smoking; 2004. 2. Sandler DP, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(24):1994-2003. 3. Crane MM, et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5(8):639-

*Percentage of deaths attributable to specific smoking-related diseases, 1997–2001.

644. 4. Miligi L, et al. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36(1):60-69. 5. Roman GC. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20(Suppl 2):91-100. 6.

†Includes secondhand smoke deaths.

Willigendael EM, et al. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1158-1165.

1. CDC. MMWR. 2005;54:625–628.

Annual Deaths Attributable to

Four Stages of the Tobacco Epidemic:

Tobacco: Worldwide Estimates

Mortality Is Increasing in Many Countries1

% of Total Deaths Attributable to Tobacco*

Russian Federation

• Eastern Europe

• Western Europe,

• Southern Europe

• Southeast Asia

• Latin America

If current smoking patterns continue, deaths from smoking in Asia—home to a third of

the world's population—are expected to increase by 2020 to 4.9 million annually.2

1. Lopez AD, et al. Tobacco Control. 1994;3:242-247. 2. Shafey O, et al (eds). Tobacco Control Country Profiles 2003,

*Regional estimates in 2000 in men aged >35 years.

American Cancer Society; 2003; Atlanta, Georgia. Available at:

1. Mackay J, Eriksen M. The Tobacco Atlas. Second Ed. World Health Organization; 2006.

Smoking Reduces Survival an

What's in a Cigarette?

Average of 10 Years

Results From a Study of Male Physician Smokers in the United Kingdom

� Tobacco smoke: ≥4000 chemicals, ≥250 toxic or

Chemical in Tobacco Smoke2

Physician Nonsmokers

Physician Smokers

Car exhaust fumes

Industrial solvent

� Nicotine is addictive, but not carcinogenic3

� Smoking cigarettes with lower tar and nicotine

provides no health benefit4

1. National Toxicology Program. 11th Report on Carcinogens; 2005. Available at: http://ntp-server.niehs.nih.gov. 2. Mackay J, Eriksen M. The Tobacco Atlas. World Health Organization; 2006. 3. Harvard Health Letter. May 2005. 4.

1. Doll R, et al. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527.

Surgeon General's Report. The Health Consequences of Smoking; 2004.

Mechanisms of Action:

What Does Secondhand Smoke Do?

How Smoking Causes Disease

� Estimated lung cancer risk increased by

– Direct respiratory cell exposure to potent mutagens

and carcinogens in tobacco smoke

� Believed to cause and worsen diseases such as

� Ischemic heart disease

asthma, COPD, and emphysema2

– Toxic products in the bloodstream create a

� Increases risk for developing heart disease by

pro-atherogenic environment

– Leads to endothelial injury and dysfunction,

� Increases risk of nonfatal acute myocardial

thrombosis, inflammation, and adverse lipid profiles

infarction in a graded manner3

� Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

– Accelerated decline in respiratory function

1. News release, June 27, 2006; US Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2006pres/20060627.html. 2. Mackay J, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. World Health

1. Surgeon General's Report. The Health Consequences of Smoking; 2004.

Organization; 2002. 3. Teo KK, et al. Lancet. 2006;368:647-658.

What Does Secondhand Smoke Do

Smoking During Pregnancy

to Infants and Children?

� Almost 60% of US children are exposed to secondhand smoke1

� Exposure during pregnancy associated with1–3

� In some countries, ≥80% of youth live in homes where others smoke

– Increased risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, sudden infant

in their presence2

death syndrome (SIDS); eg

� Secondhand smoke increases disease burden and hospitalisation in

infants and children. For example:

– Low-birth weight

– UK - 17,000 children under the age of 5 years hospitalised annually3

• 4-fold risk1: eg, 9700–18,600 cases related to secondhand

– Australia - 56% higher risk for hospitalisation if mother smoked in same

smoke annually in US*3

room as infant, 73% if smoked while holding infant, and 95% if smoked

– Impaired infant lung function2

while feeding infant (N = 4486)4

– Hong Kong - higher likelihood for hospitalisation for infants living with

– Possible association with cognitive and

any smoker at home with poor smoking hygiene (<3 metres away)5

1. Secondhand smoke; Fact sheet, June 2006. Available at:

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/factsheets/secondhand_smoke_factsheet.htm. 2. Mackay J, Eriksen M. The Tobacco

1. Fagerström K. Drugs. 2002;62(Suppl 2):1–9. 2. Le Souef PN. Thorax. 2000;55:1063–1067.

Atlas. World Health Organization; 2006. 3. Fagerstrom K. Drugs. 2002;62(suppl 2):1-9. 4. Blizzard L, et al. Arch

3. Mackay J, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. World Health Organization; 2002. 4. Hellstrom-Lindahl E,

Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:687-693. 5. Leung GM, et al. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:687-693.

et al. Respiration. 2002;69:289-293.

Importance of NOT Smoking

Why Quit? Potential Lifetime Health

Benefits of Quitting Smoking

Cardiovascular heart disease (CHD) risk is similar to never smokers

Rate of Infants with Low-Birth Weight

Lung cancer risk is 30-50% that of continuing smokers

in Taiwanese Infants by Smoking Status of the Mother (N=9499)

Stroke risk returns to the level of people who have never

smoked at 5-15 years post-cessation

CHD: excess risk is reduced by 50%

Lung function may start to improve

with decreased cough, sinus

congestion, fatigue, and shortness of

Rate of Infants With

Low Birth Weight

Never Smoked Quit Smoking‡

1. CDC. Surgeon General Report 2004: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/sgr_2004/sgranimation/flash/index.html. American Cancer Society. Guide to Quitting Smoking. Available at: http://www.cancer.org. Accessed June 2006. 2. American Cancer Society. Guide to Quitting Smoking. Available at: http://www.cancer.org. Accessed June 2006. 3.US Department of Health & Human Services. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon

†P<0.05 vs never smoked. ‡Before or during first trimester.

General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Office on Smoking and Health. 1990. Available at:

1. Wen CP, et al. Tob Control. 2005;14(Suppl 1):i56–i61.

http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/C/T/. Accessed July 2006.

Quitting at Any Age May Increase

Quitting at Any Age May Increase

Results From a Study of Male Physician Smokers in the United Kingdom

Results From a Study of Male Physician Smokers in the United Kingdom

Stopped Age 55-64

Stopped Age 45-54

Cigarette Smokers

Cigarette Smokers

1. Doll R, et al. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527.

1. Doll R, et al. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527.

Quitting at Any Age May Increase

Risk of Cardiovascular Disease

(CVD) Reduced By Quitting Smoking

Results From a Study of Male Physician Smokers in the United Kingdom

Stopped Age 35-44

Cigarette Smokers

� Quitting associated with

– 36% reduction in odds of all-cause mortality among patients with

coronary heart disease (CHD)1

– Decreases in CVD events in cardiac patients, even in those who

� Quitting sooner appears most beneficial

*Defined as self-reported smokers who were cotinine negative.

1. Doll R, et al. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527.

1. Critchley JA, Capewell S. JAMA. 2003;290:86-97. 2. Twardella D et al. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2101–2108.

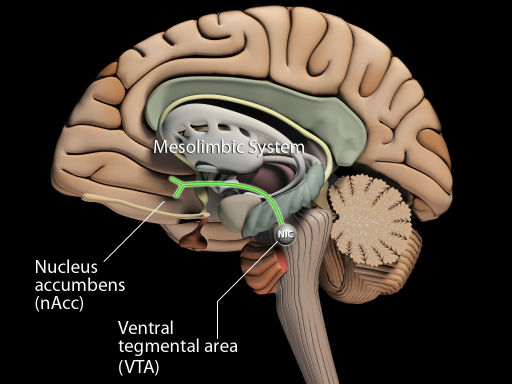

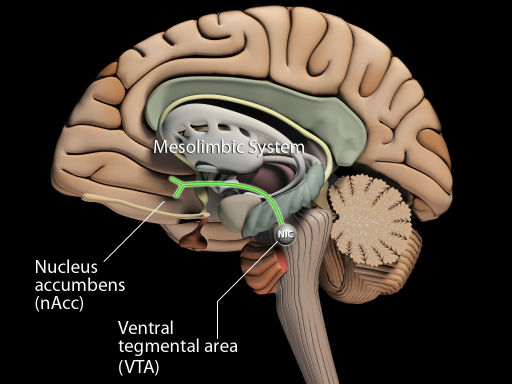

Mechanism of Action of Nicotine in

the Central Nervous System

Tobacco Dependence

and Treatment Strategies

Nicotinic Receptor

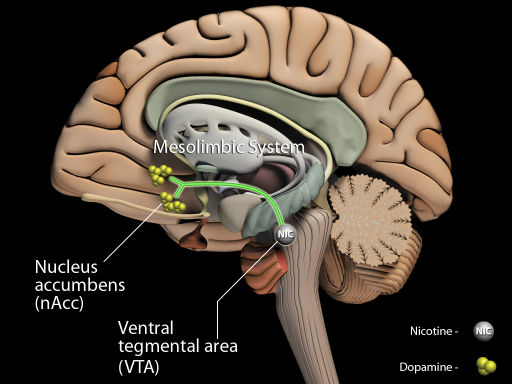

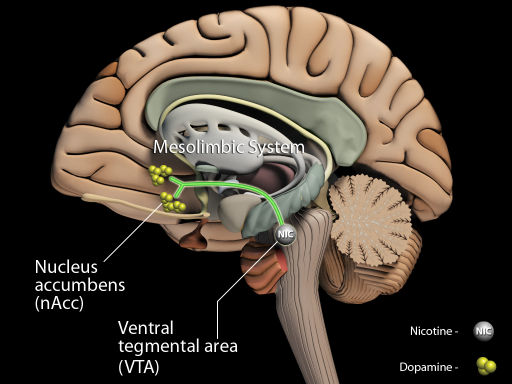

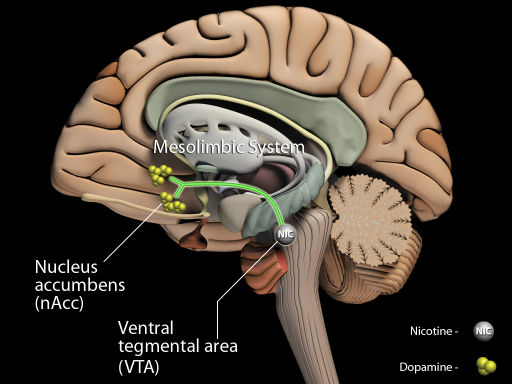

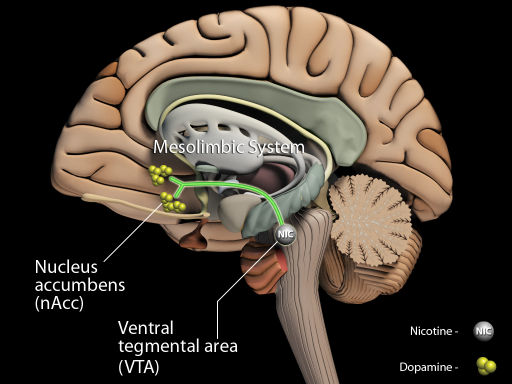

Nicotine binds preferentially to nicotinic acetylcholinergic (nACh) receptors in the central nervous system; the primary is the α4β2 nicotinic receptor in the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)

After nicotine binds to the α4β2 nicotinic receptor in the VTA, it results in a release of dopamine in the Nucleus Accumbens (nAcc) which is believed to be linked to reward

Nicotine Stimulates Dopamine

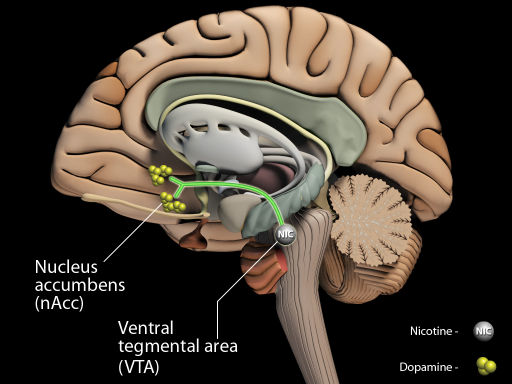

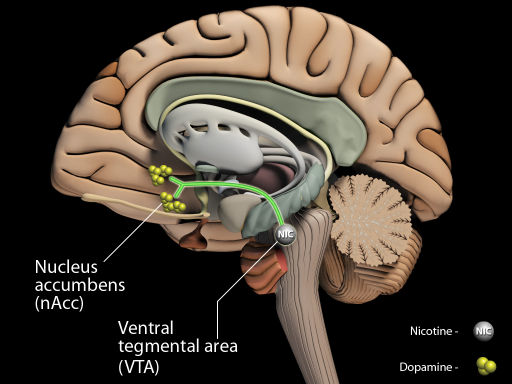

Nicotine May Cause Up-Regulation and

Desensitization of Receptors Resulting in

� Nicotine activates α4β2 nicotinic receptors in the ventral

� Tolerance typically develops after long-term nicotine use1

tegmental area resulting in dopamine release at the

� Tolerance is related to both the up-regulation (increased number)

nucleus accumbens. This may result in the short-term

and the desensitization of nicotine receptors in the VTA1

reward/satisfaction associated with cigarette smoking.

� A drop in nicotine level, in combination with the up-regulation and

decreased sensitivity of the nicotinic receptor, can result in withdrawal symptoms and cravings1

� Smokers have the ability to self regulate nicotine intake by the

frequency of cigarette consumption and the intensity of inhalation1

� In order to maintain a steady nicotine level, smokers generally titrate

their smoking to achieve maximal stimulation and avoid symptoms

of withdrawal and craving2

− α4β2 Nicotinic Receptor

Adapted from Picciotto MR, et al. Nicotine and Tob Res. 1999: Suppl 2:S121-S125.

1. Schroeder SA. JAMA. 2005;294:482-487. 2. Jarvis MJ. BMJ. 2004; 328:277-279.

The Cycle of Nicotine Addiction

So Why Do People Smoke?

� Nicotine binding causes an increase in

Addiction – Habitual psychological and physiological dependence

release of Dopamine1,2

on substance or practice which is beyond voluntary control

� Dopamine gives feelings of pleasure

– Stedman's Medical Dictionary

� The Dopamine decrease between

� Since at least the 1988 Surgeon General's Report1

cigarettes leads to withdrawal symptoms of irritability and stress1

– Addiction defined as compulsive use despite damage to the

� The smoker craves Nicotine to release

individual or society and drug-seeking behavior can take

more Dopamine to restore pleasure

precedence over important priorities

– Addiction persists despite a desire to quit or even repeated

� Competitive binding of Nicotine to

nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors causes prolonged activation,

� Most people smoke primarily because they are addicted

desensitization, and upregulation2

� As Nicotine levels decrease, receptors

revert to an open state causing

� There is a clear link between smoking, nicotinic

hyperexcitability leading to cravings1,2

receptors, and addiction2

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction; A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1988.

1. Jarvis MJ. BMJ. 2004; 328:277-279. 2. Picciotto MR, et al. Nicotine and Tob Res. 1999: Suppl 2:S121-S125.

2. Jarvis MJ. BMJ. 2004;328:277-279.

Nicotine Addiction: A Chronic

Tobacco Dependence and Environmental

Relapsing Medical Condition

Behavior Reinforcement

� True drug addiction1� Requires long-term clinical intervention, as do other addictive

� Pharmacologic effects

– Nicotine is a primary reinforcer

– Failure to appreciate the chronic nature of nicotine addiction

� Non-pharmacologic effects

• Impair clinicians' motivation to treat tobacco dependence long-term

– Environmental/social stimuli associated with smoking

• Impede acceptance that condition is comparable to diabetes,

play a role in reinforcing nicotine dependence

hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, and requires counseling, support, and appropriate pharmacotherapy

– Environmental/social stimuli enhance the reinforcing

effects of nicotine

– The nature of addiction, not the failure of the individual3

Direct pharmacologic effects of nicotine are necessary but not

• Long-term smoking abstinence in those who try to quit unaided† = 3%–5%

sufficient to explain tobacco dependence; these effects

• Most relapse within the first 8 days

must take into account the environmental/social context

in which the behavior occurs

1. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; June 2000. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/default.htm. 2. Jarvis MJ. Why people smoke. BMJ. 2004;328:277-279.

1. Caggiula AR et al. Psychol Behavior. 2002;77:683–687.

Withdrawal Syndrome: a Combination of

Why Some Smokers May Need More

Physical and Psychological Conditions, Making

Smoking Hard to Treat1,2

Withdrawal Syndrome

� Studies show some groups may be less

frustration, or anger

– Higher level of dependence1

Increased appetite

• Cigarettes per day

(may increase or

• Time to first cigarette upon awakening

with quitting)1,2

– Living with a current smoker1

– Fewer educational qualifications2

– Lower socioeconomic class2

Difficulty concentrating

– Co-morbid psychiatric disorders3

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV-TR. Washington, DC: APA; 2006: Available at http://psychiatryonline.com. Accessed November 7, 2006. 2. West RW, et al. Fast Facts: Smoking Cessation. 1st ed.

1. Hyland A et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S363-S369. 2. Chandola T et al. Addiction. 2004;99:770-777.

Oxford, United Kingdom. Health Press Limited. 2004.

3. Kalman D et al. Am J Addict. 2005;14:106–123.

Multiple Quit Attempts

Most Smokers Are Willing to

� More than 70% of US smokers have attempted to quit1

� Of smokers who relapsed following a quit

– Approximately 46% try to quit each year

– Less than 5% who try to quit are abstinent 1 year later

– 98% were willing to try again

– Similar percentages in countries with established tobacco control

programs (eg, Australia, Canada, UK)2

– 50% immediately

• 30% to 50% try to quit; <5% achieve long-term abstinence

– 28% within 1 month

� Some smokers succeed after making several attempts3

� Of those willing to try again immediately

– Past failure does not prevent future success

– Percentage did not differ based on time since

– Length of prior abstinence is related to quitting success

� Some smokers may prefer a waiting period

before attempting to quit again

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000. 2. Foulds J, et al. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2004;9:39–53. 3. Grandes G, et al. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:101–107.

1. Joseph A, et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:1075–1077.

Length of Prior Abstinence Is

Related to Quitting Success

Advice and Support

� Previous quit attempts of ≥ 3 months

� All smokers should be1

positively predicted sustained,

– Advised to quit (the "5As")

– Offered assistance irrespective of motivation

biochemically confirmed abstinence1

� Three types of non-pharmacologic therapies are

– N = 1768; OR* = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.1–2.7

– Practical counseling (problem solving/skills training)

� Duration of previous quit attempts

– Social support as part of treatment

influenced continuous abstinence at 6

– Securing social support outside of treatment

� Effectiveness increases with treatment intensity1,2

– N = 509; OR* = 1.73; 95% CI = 1.09–2.75

1. Fiore MC, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; June 2000. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/default.htm.

*OR = odds ratio.

2. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation in

1. Grandes G et al. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:101–107. 2. Aubin HJ et al. Addiction. 2004;99:1206-1218.

primary care. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=299611. Accessed September 2006.

Tobacco Dependence Support:

The "5As": Ask About Tobacco Use

� Identify and document tobacco use status for

� Ask about tobacco use

every patient at every visit

� Implement an office-wide system that ensures

� Assess willingness to make a quit attempt

tobacco-use status is queried and documented

� Assist in quit attempt

– Expand vital sign documentation to include tobacco

� Arrange follow-up

– Tobacco-use stickers on charts

– Computer reminder systems for electronic medical

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

The "5As": Assess Willingness to

The "5As": Advise to Quit

Make a Quit Attempt

� In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every

tobacco user to quit at least once per year

� Is the tobacco user willing to make a quit attempt

• "I think it is important for you to quit smoking now, and I can help

– If patient is willing to attempt quitting, offer assistance

– If patient is unwilling to quit now, provide motivational

• "As your clinician, I need you to know that quitting smoking is very

important to protecting your health now and in the future."

• Tie tobacco use to health/illness (reason for office visit),

social/economic costs, motivation level, and impact on others (children)

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

The "5As": Assist in Quit Attempt

The "5As": Arrange Follow-up

� For the patient willing to make a quit attempt, use

� Schedule follow-up contact, preferably within the first

counseling and pharmacotherapy

week after the quit date

– Provide practical counseling (problem solving and skills training)

� Follow-up can occur either in person or via telephone

– Provide social support

� Follow-up actions

– Offer pharmacotherapy as appropriate

– Congratulate success

– Provide supplementary materials

– Review circumstances of lapse – elicit recommitment to

• World Health Organization: www.who.int

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: www.cdc.gov/tobacco

– Identify and anticipate challenges

• Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco: www.srnt.org

– Assess pharmacotherapy use

– Consider need for referral to formal program

– Consider referral for more intensive treatment

• Telephone or internet-based

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

1. Fiore MC, et al. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. June 2000.

Patient Satisfaction Linked With

Effectiveness Increases with

"5A" Interventions

Treatment Intensity

� Regardless of readiness to quit, smokers receiving 5A

interventions were more satisfied with their health care

Minimal Counseling

13.4 (10.9, 16.1)

(less than 3 minutes)

Low Intensity Counseling

16.0 (12.8, 19.2)

(3 to 10 minutes)

Higher Intensity Counseling

22.1 (19.4, 24.7)

(more than 10 minutes)

Very Satisfied (%)

N=1160. *P<0.0001; †P= 0.0014.

1. Fiore MC, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. US Department of Health and

1. Conroy MB, et al. Nicotine Tob Research 2005;7(Suppl 1):S29–S34.

Human Services. Public Health Service; June 2000. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/default.htm.

Pharmacotherapy for Tobacco

for Smoking Cessation

� Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)1

– Long acting1-3

Physician advice1

Brief vs no advice (usual care)

1.74 (1.48–2.05)

Intensive vs minimal advice

1.44 (1.24–1.67)

– Short acting1-3

Individual counseling2

Vs minimal behavior intervention

1.56 (1.32–1.84)

Group counseling3

2.04 (1.60–2.60)

Vs no intervention

2.17 (1.37–3.45)

• Sublingual tablets/lozenges

Proactive Telephone counseling4

� Antidepressants4

Vs less intensive interventions

1.56 (1.38–1.77)

– Bupropion SR4

Vs no intervention

1.24 (1.07–1.45)

– Nortriptyline3 (not approved for smoking cessation)

*Abstinence assessed at least 6-months following intervention.

1. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD000165. 2. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001292. 3. Stead LF, Lancaster T. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):

1. Silagy C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000146. 2. Stead L, et al. Int J Epidemiol.

CD001007. 4. Stead LF et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002850. 5. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Cochrane

2005;34:1001–1003. 3. Henningfield JE, et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:281-299.

Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD001118.

4. Hughes JR et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD000031.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT): Nicotine

Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

Delivery by Cigarettes and NRT Products

Cigarette (nicotine delivery, 1-2 mg)

Gum (nicotine delivery, 4 mg)

– NRT has been shown to be safe and effective in

Nasal spray (nicotine delivery, 1 mg)

helping people stop using cigarettes when used as

Transdermal patch

part of a comprehensive smoking cessation program1

� Delivers nicotine that binds to the nAChR

� Does not generally counter the additional

satisfaction from smoking1

� NRTs may not deliver nicotine to the circulation

as fast as smoking2

80 90 100 110 120

Time post-administration (minutes)

1. American Heart Association website: http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4615, accessed November 5, 2006. 2. Sweeney CT, et al. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:453-467.

1. Sweeney CT, et al. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:453-467.

Efficacy of Nicotine Replacement

Bupropion SR (Zyban®)

� ZYBAN (bupropion SR hydrochloride) is a non-

nicotine sustained-release tablet for smoking

1.66 (1.52–1.81)

� Initially developed as an antidepressant, later

1.81 (1.63–2.02)

found to have efficacy in smoking cessation1

2.35 (1.63–3.38)

� There are 2 potential MOAs:

2.14 (1.44–3.18)

– Blocks reuptake of dopamine2,3– Non-competitive inhibition of α3β2 and α4β2 nicotine

2.05 (1.62–2.59)

Combination vs single type

1.42 (1.14–1.76)

Any NRT vs control

1.77 (1.66–1.88)

1. Package Insert. bupropion SR hydrocloride [Zyban®]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2. Henningfield JE, et al. CA Cancer J Clin.

1. Silagy C et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000146. 2. Stead L, Lancaster T. Int J Epidemiol.

2005;55:281–299. 3. Foulds J, et al. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2004;9:39–53. 4. Slemmer JE, et al. J Pharmacol

Exp Ther. 2000;295:321–327. 5. Roddy E. Br Med J. 2004;328:509–511.

Comparison of Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

Champix (varenicline): A Highly

and Bupropion SR Therapy for Quitting Smoking1

Selective α4β2 Receptor Partial Agonist

� Only study comparing NRT and antidepressant

therapy for quitting smoking2

Placebo (n = 160)

Nicotine Patch (n = 244)

Bupropion SR (n = 244)

Bupropion SR + Patch (n = 245)

Binding of nicotine at the α4β2 nicotinic receptor

Champix is an α4β2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist,

in the VTA is believed to cause release of

a compound with dual agonist and antagonist

dopamine at the nAcc

activities. This is believed to result in both a lesser amount of dopamine release from the VTA at the

nAcc as well as the prevention of nicotine binding at

1 Year Continuous Abstinence

the α4β2 receptors.

(Week 2 to Week 52)

1. Coe JW et al. Presented at the 11th Annual Meeting and 7th European Conference of the Society for Research on

*P ≤ 0.001 vs placebo and patch alone.

Nicotine and Tobacco. 2005. Prague, Czech Republic. 2. Picciotto MR et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999; Suppl 2:S121-

1. Jorenby DE, et al. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:685–691. 2. Talwar A et al. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:1517–1534.

Varenicline Mechanism of Action:

1: Findings from the STOP survey

Efficacy for Tobacco Dependence

� Efficacy of varenicline in tobacco dependence

Other things have higher priority

– Believed to result from partial agonist activity at the α4β2

nicotinic receptor

Helping patient stop is part of job

� By preventing binding of nicotine, varenicline

– Reduces craving and withdrawal symptoms (agonist activity)

Stopping is primarily down to willpower

– Produces a reduction of the rewarding and reinforcing effects of

smoking (antagonist activity)

Smoking is addictive

� The most frequently reported adverse events (>10%)

Smoking is a medical condition

with varenicline were nausea, headache, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

Smoking is a lifestyle choice

Pfizer-sponsored survey: Interviews with 2836 smoking and non-smoking general practitioners in 16 countries

1. Champix Summary of Product Characteristics. Pfizer Ltd, Sandwich, UK. 2006.

1: Apparent paradoxes

1: What does this mean?

Smoking is an addiction

stopping is a matter of

Need a message that recognises the

duality of beliefs about smoking

Smoking should be

is primarily a lifestyle

"Smokers must take responsibility for

regarded as a medical

stopping smoking, and they will need

determination to succeed; but when

determination is not enough, the

Helping patients to stop

other things have a

physician has effective tools to help the

is part of the job

2: A simple model of nicotine

2: The process of stopping

Chronic intake of

Motivational tension

When smokers think about their smoking

most, they are unhappy about it, but many

1. Think it meets certain needs

2. Is a source of enjoyment

3. Think stopping will be difficult

controlling motivation

Something needs to prompt them to make a quit attempt using a method that maximises

their chances of success

A biologically driven

Cues associated with

Experience of relief

of nicotine withdrawal

The treatment needs to be of a type and

when nicotine levels

symptoms leads to

intensity that meets the individual smoker's

in the brain are low

expectations of more

needs, and available whenever and for as

long as the smoker needs it

3: The physician's role

3: A simple consultation model

Yes, I know I should

Every month you put off

• To give professional, expert

stopping, you may lose another

advice on health matters

week off your life

• To provide treatment to those

You have to question whether it is

worth the pain and suffering

who want and need it

you will endure later

Now is not a good time

Now is always a good time for

stopping, smoking doesn't really

• Now is a good time to stop

• It is always worth having

I am worried that

Most smokers make many

attempts before they succeed

to a clear, firm

• There are things available that

Addictions can be conquered,

will make it easier

especially when you get help

It's never too late…

Source: http://csot.semmelweis.hu/download/gradualis/angol/vajer.peter-smoking.cessation.pdf

HEALTH CARE BENEFITS IN CANADA March 2006 We Take a Closer Look Wendy Murkar Vice-President, Claims Administration Green Shield Canada State of health care in Canada Issues affecting benefit utilization Impact on benefit plan design STATE OF HEALTH CARE IN CANADA Benchmarking of

20th International Congress for Analytical Psychology; Kyoto, August 28 to September 2, 2016 Pre-Congress Workshop on Authentic Movement: Danced and Moving Active Imagination ANIMA MUNDI IN TRANSITION: Cultural, Clinical, And Professional Challenges (English) Psyche is as much a living body as body is living psyche.