Levitra enthält Vardenafil, das eine kürzere Wirkdauer als Tadalafil hat, dafür aber schnell einsetzt. Männer, die diskret bestellen möchten, suchen häufig nach levitra kaufen ohne rezept. Dabei spielt die rechtliche Lage in der Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle.

Social mishap exposures for social anxiety disorder: an important treatment ingredient

Social Mishap Exposures for Social Anxiety Disorder: An Important

Treatment Ingredient

Angela Fang, Alice T. Sawyer, Anu Asnaani, and Stefan G. Hofmann, Boston University

Conventional cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder, which is closely based on the treatment for depression, has been shownto be effective in numerous randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this intervention is more effective than waitlist control group andplacebo conditions, a considerable number of clients do not respond to this approach. Newer approaches include techniques specificallytailored to this particular population. One of these techniques, social mishap exposure practice, is associated with significant improvement intreatment gains. We will describe here the theoretical framework for social mishap exposures that addresses the client's exaggerated estimationof social cost. We will then present clinical observations and outcome data of a client who underwent treatment that included such socialmishap exposures. Findings are discussed in the context of treatment implications and directions for future research.

S OCIAL anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most

common anxiety disorders in the U.S., with a lifetime

). The cognitive-behavioral model proposes that

and 12-month prevalence of 12.1% and 7.1%, respectively

SAD develops and is maintained by maladaptive cognitive

and behavioral processes, which negatively reinforce

defined by a persistent fear of negative evaluation by others

avoidance strategies and contribute to a cycle of anxiety

in social or performance situations

) and is associated with significant impair-

). The following discussion is based on the mainte-

ment in occupational, academic, and interpersonal func-

nance model developed by which

emphasizes the importance of social cost and social mishap

heterogeneous condition, as individuals with SAD may vary

exposures. A more detailed explanation of this model is

in the kinds of people, places, and situations that cause fear.

described elsewhere ). According to this

However, common fears include formal public speaking,

model, an individual with SAD experiences apprehension

speaking up in a meeting or class, and meeting new people

upon entering a social situation because they perceive the

(Ruscio et al.). It also appears that while these situations may

social standards to be excessively high and experience

differentially provoke anxiety for each individual, most

doubt about being able to meet those standards. Once

clients with SAD share similar underlying core fears, such

confronted with social threat, individuals with SAD

as being rejected, looking stupid or unintelligent, expressing

experience heightened self-focused attention, in which

disagreement or disapproval, and being the center of

attention is turned inwardly toward one's internal physical

sensations and anxious thoughts . Self-

Theoretical Models of SAD

focused attention simultaneously triggers a variety of other

There is strong empirical evidence supporting a

cognitive processes, including a negative self-perception

cognitive-behavioral model of SAD

(e.g., "I am such an inhibited idiot"), high estimated socialcost (e.g., "It will be a catastrophe if I mess up this

Video patients/clients are portrayed by actors.

"), low perceived emotional control (e.g., "I have

no way of controlling my anxiety"), and perceived poor

Keywords: exposure therapy; social mishap exposure; social anxiety

social skills ("My social skills are inadequate to deal with this

situation"). These processes, in turn, lead the client toanticipate a social mishap in which one actually does

something to embarrass oneself, cause negative evaluation,

2012 Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

or otherwise violate social norms. This expectation

contributes to the use of avoidance strategies and safety

intentionally create the feared negative consequences of a

behaviors to cope with the anxiety and to avoid the feared

feared social situation. As a result, patients are forced to

outcome, which leads to post-event rumination about one's

reevaluate the perceived threat of a social situation after

performance in a social situation (

experiencing that social mishaps do not lead to the feared

The rumination and avoidance behaviors ultimately feed

long-lasting, irreversible, and negative consequences. A

back into continued apprehension in social situations.

more detailed description of this model is presented in

An important reason why SAD is maintained in the

presence of repeated exposure to social cues is because

Early data suggest that treatment protocols that incor-

individuals with SAD engage in a variety of avoidance and

porate social mishap exposures show considerably greater

safety behaviors to reduce the risk of rejection (e.g.,

efficacy than traditional CBT protocols, which are typically

). These avoidance tendencies, in turn, prevent

associated with only moderate effect sizes (e.g.,

patients from critically evaluating their feared outcomes

Other, more recent studies that include social

and other catastrophic beliefs, leading to the maintenance

mishap exposures (among other techniques) report

and further exacerbation of the problem. Social mishap

considerably larger efficacy rates. For example,

exposures directly target the patients' exaggerated social

reported effect sizes ranging between

cost by helping patients confront and experience the actual

1.41 (pretest to posttest) and 1.43 (pretest to 12-month

consequences of such mishaps without using any avoidance

follow-up; Clark et al.). Similar efficacy data (pre-post effect

size of 1.54) have been found in an early pilot trial).

Obviously, social mishap exposures are not the only

Social Mishap Exposures

aspect that distinguishes traditional CBT protocols from

Consistent with the notion that clients with SAD over-

more modern approaches Depending on

estimate the social costs associated with social mishaps, high

the specific treatment protocol, other aspects include

estimated social costs have been proposed to be an

strategies for attention retraining, changes in self-perception,

important mediator of treatment change (

and post-event rumination. However, in-vivo social mishap

. This hypothesis has been subjected to empirical

exposures are the most obvious differences to traditional

testing, and substantiated in a treatment outcome study that

CBT approaches, which have primarily employed in-session

compared cognitive-behavioral group therapy, exposure

role-play situations with the goal to identify and replace

therapy (without explicit cognitive intervention), and a

maladaptive general automatic thoughts. The purpose of the

wait-list control group . It was found that

current paper is to present a case example from a group

changes in estimated social costs mediated treatment

cognitive-behavioral therapy protocol that emphasizes social

change between pre- to posttreatment in the two active

mishap exposures, and to discuss the benefits and challenges

treatment conditions ). These empirical

associated with its successful implementation. The case that

findings therefore support the utility of social mishap

follows discusses a treatment-seeking individual who pre-

exposures in addressing this overestimation of costs

sented to an outpatient clinic specializing in the treatment of

associated with a social mishap. This is accomplished by

mood and anxiety disorders.

having the client behave in a way that causes a social mishapby purposefully violating the client's perceived social norms

(e.g., singing in a subway).

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV;

The difference between social mishap exposures and

) was administered at the

exposure practices that have been typically used in

intake evaluation. The ADIS-IV is a semistructured clinical

cognitive-behavioral therapy protocols for SAD is that social

interview that assesses mood and anxiety disorders

mishap exposures cause clients to experience the feared

according to DSM-IV

outcomes that they try so hard to avoid by clearly appearing

) criteria. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS;

incompetent, crazy, obnoxious, and so on. Standard

) is a 24-item clinician-administered mea-

exposure practices of patients with SAD are typically

sure that assesses fear and avoidance of social situations

designed to make patients realize that social catastrophes

(each rated on a 0- to 3-point scale with a range of total

are unlikely to happen, and that patients are able to handle

scores from 0 to 144) in the past week. The LSAS has been

socially challenging situations despite their social anxiety

validated in clinical samples, and has high internal

(e.g., ). In contrast, the goal of

consistency ). The LSAS was

the social mishap exposures is to purposely violate the

administered at every session throughout the course of

patient's perceived social norms and standards in order to

treatment, and also at six major time points: baseline, Week

break the self-reinforcing cycle of fearful anticipation and

8, posttreatment, 1-month follow-up, 3-month follow-up,

subsequent use of avoidance strategies. Patients are asked to

and 6-month follow-up.

Social Mishap Exposures for SAD

In addition, Mary described residual symptoms of

was a 41-year-old married, Caucasian, insurance

depression that never resolved after having lost her job

company analyst, who lived with her husband and two

2 years ago. She had been working as a research analyst at

children. She came to the clinic seeking outpatient

a local bank, and had been fired due to the bad economy

psychotherapy for her social anxiety. She presented with

as well as poor reviews from clients. She reported feeling

primary concerns about having suffered from anxiety

like she had lost interest in many activities that she used to

throughout her life. She reported "always feeling awkward

enjoy, such as shopping and seeing friends, and has been

and self-conscious in groups," and not knowing what it was

feeling excessively guilty and doubtful of her ability to

until she read more about social anxiety in online help

hold her current job. Mary reported not having ever

forums. Mary described her social anxiety as being at its

received cognitive-behavioral therapy for either her

worst when meeting new people in unstructured social

depression or social anxiety concerns, but that she had

gatherings, such as parties and work events, and she

tried supportive therapy with a variety of health-care

described the anticipatory anxiety to be so crippling that

professionals, including counselors and licensed social

she would often turn down invitations. She reported

workers. Last year, Mary visited a psychiatrist to receive

feeling nervous about what to say, asking too many

psychopharmacological interventions for her depression,

questions, and not feeling like herself. Mary's anxiety had

which she reported being effective.

affected her life in many ways. For example, in college she

Based on information obtained from her baseline

had majored in mathematics to avoid courses that

assessment, Mary received a primary diagnosis of SAD,

involved formal presentations; she had lost jobs; and,

generalized subtype, and a diagnosis of major depressive

ultimately, she had chosen a career that involved limited

disorder (MDD), in partial remission. She had no other

social interactions. When Mary was asked what she was

comorbid psychiatric disorders, but reported a family

concerned would happen in these situations, she could

history of MDD. She had also been taking Wellbutrin

not initially give an answer, but later responded that she

(200 mg) for a year for her depression, which she

was worried that others would judge her negatively, reject

discontinued through a psychiatrist-guided taper prior

her or hurt her feelings. She further explained that her

to starting group treatment. Her baseline LSAS score of

worst fear was that she would alienate everyone, even

90 reflected a severe level of SAD.

those who were close to her.

Mary described recent concerns about not performing

Treatment Procedure

well at work due to extreme distress when preparing for

The treatment consisted of 12 weekly, 2.5-hour sessions

group meetings and presentations and extreme anxiety

of group cognitive-behavioral therapy with four to six

making work-related phone calls. During her assessment,

members in total. The protocol was implemented by two

it was gleaned that Mary was worried that she was going to

therapists, master's-level doctoral candidates, who fol-

get fired from her job because she had put off making

lowed the treatment manual.

some important phone calls, and clients had called her

Week-to-week LSAS scores were determined by meeting

supervisor to complain. She described being concerned

separately with a trained independent evaluator before

that she would be perceived as incompetent or un-

the start of each group.

intelligent by clients and coworkers. Mary also hadconcerns about wanting to be more involved in her

Sessions 1–2: Psychoeducation and Cognitive Restructuring

children's lives at school because her husband worked

The first session consisted of an introduction of

much longer hours, but she was very apprehensive about

cotherapists and group members and their reasons for

attending parent-teacher conferences, parent-teacher

seeking treatment. Psychoeducation about the nature of

association meetings, and making small talk with other

SAD as a learned habit and the adaptive aspects of anxiety

mothers at her sons' sporting events and school concerts.

were presented and discussed. An overview of treatment

She described being particularly afraid of unstructured

was presented, with an introduction to the primary

small talk with same-age parents or teachers because they

treatment techniques, which included cognitive restruc-

would think she was awkward. Mary explained that she

turing and in-vivo exposures. The session concluded with

feared other mothers perceiving her as an uninvolved and

identification of automatic negative thoughts related to

bad parent. She also reported severe avoidance of her

attending group treatment specific to each client, and

children's extracurricular events, with the exception of

assignment of thought records (e.g., monitoring of such

dropping them off and picking them up.

automatic thoughts) for homework.

Session 2 began with a review of the homework and an

invitation from group members to share their thought

records. The majority of the session focused on presenting

Client name and other identifying information have been

changed to protect client confidentiality.

the exposure rationale to the group by discussing the role of

avoidance in perpetuating the cycle of anxiety. Examples of

in-session public speaking exposures were structured

safety behaviors and other avoidance behaviors were

similarly to the more traditional SAD group treatment

discussed by using specific recent examples. The short-term

exposures, the concept of purposefully experiencing social

and long-term consequences of these avoidance behaviors

mishaps was introduced very early on (typically by the

for the maintenance of the disorders were discussed. The

second or third in-session exposure) to target these

session concluded with a discussion of concerns and

avoidance behaviors. In collaboration with the other

questions about the start of public speaking exposures at

group members and Mary, the therapist generated specific

the next week's session. For homework, clients were asked

exposure tasks to provide Mary with an opportunity to

to generate a hierarchy of feared social situations for use

examine the actual consequences of what she considered to

be social mishaps. For example, during Session 5, Mary was

Mary attended the group along with four other clients.

asked to give a 3-minute speech about cloning (of which she

The other members varied in age, gender, occupation, and

had little knowledge), and her specific goals were (a) to

SAD symptom severity. At the first two sessions, Mary

make eye contact with every member of the audience at least

engaged in the discussion and appeared to relate to other

once; (b) to stop speaking suddenly in the middle of her

group members' experience of SAD. Similar to other

speech for a long pause and to count 5 "Mississippi" before

members, Mary described strong physiological reactions

resuming; and (c) to pace back and forth across the room

(e.g., racing heartbeat and sweaty palms) to anticipating an

during the entire speech. In accordance with the research

important class presentation or work meeting; she identi-

on high perceived social standards and high estimated social

fied jumping to conclusions as a major cognitive distortion

costs associated with the speech, Mary collaboratively

that emerged for her.

designed an experiment with the therapists to test howhigh the social standards and social costs were for the speech

Sessions 3–7: In-Session Exposures

and to see what would happen if she did run out of things to

Sessions 3 to 7 consisted primarily of conducting

say. Mary reported an anticipatory anxiety of 80 (on a

in-session public speaking exposures, in which each group

100-point scale of subjective units of distress, or SUDS), a

member gave a 3-minute speech on an impromptu topic

peak anxiety of 80, and a final anxiety of 45 at the end of the

that he or she had rated highly on a speech topics

exposure. She described experiencing significant anxiety

hierarchy. Specific behavioral goals were collaboratively

when she stopped speaking at first, but that it gradually came

agreed upon with the therapist at the start of the exposure

down over time. She stated at the end of the exposure that

to address elimination of safety behaviors during the

pausing during the speech was not as bad as it sounded at

exposure, as well as the individual client's core fears.

first. Upon reviewing the videotape feedback, Mary noted

Incorporating social mishap during the speech exposure

that the person in the video did not actually look that

was introduced as a way to disconfirm negative beliefs about

anxious during the long pause. This was an important

feared consequences. Furthermore, automatic thoughts

component of treatment for her, as she mentioned later that

about the speech were identified and challenged before

she was shocked by the discrepancy between how she looked

and after the exposure. Speeches, conducted in front of the

and how anxious she felt on the inside.

group, were videotaped to provide feedback to clients.

Speech exposures can be used to target other fears by

For homework, group members were requested to repeat

reevaluating the patient's estimated social costs. For

their in-session speech exposures in front of the mirror each

example, clients who fear looking silly during the speech

day three times in a row. The mirror exposures were used to

can be asked to put on a costume or prop, such as an

address clients' self-focused attention by allowing them to

attention-grabbing wig or witch's hat. Those who fear

receive live feedback on their appearance (akin to videotape

appearing unintelligent may say something factually incor-

feedback during the session), and to give them a chance to

rect or mispronounce a word during the speech. Those who

engage in the repeated exposure model for anxiety

fear that they will stutter can intentionally stutter during the

speech. Speech exposures have also been used in tandem

Mary described experiencing significant anticipatory

with interoceptive exercises for individuals who fear the

anxiety leading up to these sessions, and even admitted to

physiological sensations that emerge in anticipation of or

almost skipping a session to avoid giving an impromptu

during the speech. Those individuals would conduct

speech. Her speech exposures were particularly useful and

interoceptive exercises (e.g., induced hyperventilation for

relevant for the group presentations that she had to give as

shortness of breath, running in place for racing heartbeat

part of her job. Mary's primary fear in this domain was

and sweating) for 1 minute before the start of the speech.

running out of things to say, which would cause her toengage in safety behaviors such as limiting eye contact with

Sessions 8–11: In-Vivo Mishap Exposures

the audience and freezing up in front of the group to

Sessions 8 to 11 involved targeted in-vivo mishap

minimize attention on her. As a result, while these first few

exposures that were further tailored to the individual

Social Mishap Exposures for SAD

client's core fears. The goals for the exposures were

introduction of herself to at least one individual. Mary

collaboratively discussed and agreed upon with the

reported that these between-session exercises were essential

therapists at the outset. Social costs were incorporated

to her progress, as they translated her therapeutic work to

into each exposure to target specific core fears of the

her real-life social situations and contexts.

individual client. In addition, automatic thoughts about

As stated previously, these exposure exercises should

the exposures were identified and challenged before and

specifically challenge the patient's social cost estimates

after the exposure. When group members returned from

(e.g., walking around with toilet paper hanging out of the

the exposures, the therapists led a discussion of whether

shirt, buying and minutes later returning the same book,

each exposure was successful by reviewing the clients'

walking on a busy street with the zipper of the pants wide

open, spilling water in a restaurant, asking a random woman

Mary's in-vivo mishap exposures were designed to target

on a street out on a date) to be most effective. When

her fears of inconveniencing others, being the center of

conducting these social mishap exposures, it is important to

attention, and being thought of as unintelligent. To address

clearly define the goal of the exposure situation and not to

her fear of inconveniencing others, the therapists worked

link the success or goal of the exposure to the patient's

with Mary to design an exposure in which she negotiated a

anxiety (i.e., "I want to do it nonanxiously" is not an

romantic vacation package at a nearby five-star hotel. Her

acceptable goal). Instead, the goal should be linked to

goals were to ask for tickets to a ballgame, for rose petals to

specific behaviors that allow the patients to test the

be strewn on the bed, and for a horse-drawn carriage tour of

anticipated consequences of the social mishaps. It is essential

the city. At the end of stating those three requests, her goal

that patients refrain from avoidance or safety behaviors,

was to obtain an itemized list with the final price, negotiate

such as apologizing, or any other behavior that might lessen

the price, and then reject the offer because she "changed

the patients' anxiety in the situation. For this reason, it is

her mind" without apologizing or giving any excuses. She

advisable to provide detailed instructions to the patients to

described having automatic thoughts that she would get

give them no room to engage in any such avoidance

kicked out of the hotel, and that the concierge staff would

behaviors. provides further examples of social

roll their eyes at her. Mary's anticipatory anxiety was a 90,

mishap exposures that clinicians may utilize in treatment.

her peak anxiety was a 90, and her final anxiety rating was a

Our research group has filmed a series of treatment

40. Upon completing her exposure, she stated that she was

sessions to exemplify various aspects of the intervention.

surprised by the concierge's accommodating nature,

These can be found online at the Boston University

despite her outrageous requests, and that she did not

Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory

receive the kind of negative response she had anticipated by

the concierge staff. She met all of her goals and left the

particular, the following video clips depict three treatment

exposure with a sense of accomplishment for minimizing

phases germane to the current paper: Video 1 demon-

any use of safety behaviors (e.g., apologizing excessively for

strates how to set up for an in-vivo exposure

turning down the offer).

Other exposures that Mary conducted in subsequent

Video 2 demonstrates how to conduct a social mishap

sessions addressed similar fears: interrupting a group of

people in a restaurant to practice a toast for a maid-of-

; and Video 3 demonstrates the

honor speech (targeting inconveniencing others and being

postprocessing of a social mishap exposure

the center of attention); asking strangers in a bookstore to

read the back cover of a book because she did not know howto read (targeting being thought of as unintelligent); and,

Session 12: Relapse Prevention

while wearing bandages on her face, asking people on the

The treatment concluded with a discussion of relapse

street if they were "Carl Smith" because his car was being

prevention strategies. Clients reviewed their progress,

towed (targeting inconveniencing others, being the center

discussed areas of improvement, assisted each other in

of attention, and being thought of as weird).

detecting warning signs, and generated ways to maintain

Mary was assigned between-session in-vivo exposures to

their progress. Similar to the recommendations for contin-

practice the effects of repeated exposure. She was encour-

ued use of other treatment components (e.g., cognitive

aged to be creative, be concrete in specifying the behavioral

restructuring techniques, approach to feared situations),

goals of the exposures, and to try out other group members'

ongoing use of social mishap techniques posttreatment were

exposures. During the course of treatment, opportunities

suggested in those cases where overestimated social cost and

arose for Mary to make important phone calls at work and

fear of social norm violation remained a primary issue. For

attend parent meetings at her children's school. She had

instance, Mary was encouraged to continue targeting her

assigned goals for herself that minimized the use of safety

fear of being the center of attention by engaging in behaviors

behaviors, such as not procrastinating and initiating

for which she thought she would be negatively judged. She

Table 1Examples of Social Mishap Exposures

1. Ask three people in the subway if they can spare $20.

2. Walk backwards slowly in a crowded street for three minutes.

3. Wear your shirt backward and inside out and buttoned incorrectly

in a crowded store. Goal: Look three people in the eye.

4. Pay for an embarrassing item with change, and then state that

you don't have enough and leave the store.

5. Approach people on the street asking if they can help you tie

your shoelaces when you're wearing shoes without laces.

6. Recite "Twas the Night Before Christmas" in the subway

7. Go to a fast food restaurant and only order water, then spill the

water, clean it up, and stay in the restaurant.

8. Ask multiple people in a specific and obvious location (e.g., right

Video 1. Demonstrating how to set up an in-vivo social mishap

outside XXX Park, or a T stop) where to find that location

exposure with patient.

("Excuse me, I am looking for XXX Park").

9. Ask a staff member in Barnes and Noble for their opinion

about whether to buy the Kama Sutra or the Joy of Sex, have along conversation about this, buy the books and then returnthem immediately.

10. Initiate conversations with/tell jokes to strangers in Barnes and

Noble while wearing hair in a side ponytail with bandages onface.

11. Dance or sing in the street or subway wearing attention-grabbing

12. Call Barnes and Noble, ask to place on hold The Gas We Pass

and Everybody Poops as well as a chocolate chip cookie fromthe in-house café.

13. Go to a hotel. Have the patient conduct a long conversation

with the concierge about romantic vacation packages (askingabout in-room massages, arranging horse-drawn carriageride, etc.), book a package, and then cancel for no reason

Video 2. Patient conducting in-vivo social mishap exposure in the

except changing their mind.

presence of the clinician.

14. Go to every table in a crowded restaurant asking for Joe Smith.

15. Tell someone at B & N that you don't know how to read and

ask them if they can read the back cover to you.

16. Approach group of people at bar or restaurant and ask if you

can practice a best man's toast.

17. Enter a food establishment and interrupt people asking if

they own a silver Camry because their car is being towed.

was encouraged to try out social mishap exposures that othergroup members had engaged in during the course oftreatment to target this fear (e.g., wearing bright coloredarticles of clothing, talking loudly into her cell phone in acrowded area, and opening her umbrella indoors).

Video 3. Demonstrating how to conduct postprocessing of in-vivoexposure.

Summary of Treatment

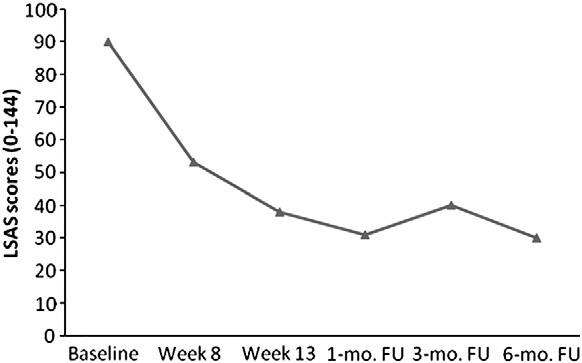

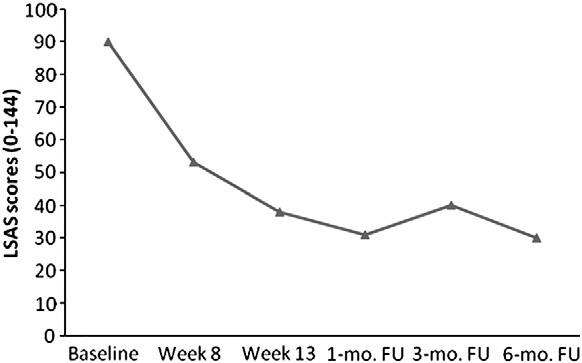

At the end of treatment, Mary's LSAS score decreased

to 38, which represented a 57.8% reduction of SADsymptoms from baseline. Mary continued to improve and

symptom severity and maintenance of such progress even

maintain her progress following acute treatment, as her

6 months later. Please see for a visual represen-

LSAS scores indicated further improvements in SAD

tation of Mary's outcome data at each time point.

Social Mishap Exposures for SAD

group format may provide additional motivation for singlepatients. At the same time, a group format provides lessflexibility to treat comorbid conditions in the context of thisprotocol. Consistent with research indicating that SADrarely occurs in isolation (amajority of the clients in the group had other comorbidclinical disorders. Although Mary's depression remained inpartial remission during the course of treatment, and inlight of research showing the negative impact thatcomorbidities such as depression have on SAD treatmentoutcomes (), the group treatment for SAD may not

Figure 1. Outcome data for case of Mary.

have been appropriate had she experienced anotherdepressive episode. It is also worth noting that the cases

presented in the current study represented a highly

Although Mary improved in a clinically meaningful way

motivated subset of individuals who participated in our

by the end of the treatment, she presented certain

group treatments, which may not be generalizable to the

challenges to the therapists who led her group. One primary

larger population of clients with SAD. This worked to our

difference in Mary's case compared to the other group

advantage because they were not only engaged in the

members was that Mary had a longer duration of illness (she

treatment, but they also served as cotherapists in the group

was the oldest member of the group) and she had a higher

by encouraging other group members to engage in

baseline severity of symptoms than the other members. She

treatment. We recommend that future treatment studies

had therefore developed highly evolved and idiosyncratic

incorporate social mishap exposures and further investi-

avoidance strategies. For example, it was not until the

gate their relative efficacy by directly comparing them to

therapists conducted a functional analysis during treatment

more traditional exposures. Additionally, although in our

that they discovered that Mary's overdelegation of work

experience all patients benefit to some extent from

(related to making phone calls) to the administrative

engaging in social mishap exposures, it is important to

assistants in the office was an avoidance strategy couched

systematically examine whether particular subsets of

in her mind as a justification for enhancing her efficiency at

patients benefit more than others (e.g., patients of certain

work. In other cases, clients have entered treatment with

age groups, clinical presentations, motivation levels).

significant stigma about seeking treatment, and have felt

Appendix A. Supplementary data

initially resistant to in-vivo exposures because of a fear of"being discovered" as having social anxiety by people in the

Supplementary data to this article can be found online

area where they were engaging in exposure exercises. These

thoughts had to be addressed directly through cognitive

restructuring to motivate members to attempt the exerciseassigned, and were even tested as predictions in the

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

exposures. It was therefore challenging for the therapists

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual

to allot relatively equal amounts of time reviewing home-

of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author.

work and exposures with each client when some clients

Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post-event

processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28,

needed inordinately more time. There were limitations of

the current study that deserve mention. Some of the

Clark, D. M., Ehlers, A., McManus, F., Hackmann, A., Fennell, M.,

limitations apply for any treatment that is administered in

Campbell, H., . . Louis, B. (2003). Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetinein generalized social phobia: A randomized placebo-controlled trial.

a group rather than individual format. Although there tends

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 1058–1067.

to be less emphasis on an individual client in a group

Clark, D. M., & McManus, F. (2002). Information processing in social

treatment, the current protocol allowed for meaningful

phobia. Biological Psychiatry, 51, 92–100.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G.

tailoring of the treatment to an individual's needs and core

Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.),

Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). New

Our clinical experience is that treatments that involve

York, NY: Guilford Press.

Davidson, J. R. T., Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Keefe, F. J., Franklin, M. E.,

social mishap exposures are not associated with greater

Compton, J. S., . . Gadde, K. (2004). Fluoxetine, comprehensive

dropout rates than traditional CBT. This is consistent with

cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social

other studies utilizing similar social mishap exposure

phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1005–1013.

DiNardo, P. A., Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety Disorders

techniques This is somewhat surprising

Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Client Interview Schedule. New York, NY:

given the highly unpleasant nature of the exposure tasks. A

Oxford University Press.

Heimberg, R. G., Dodge, C. S., Hope, D. A., & Kennedy, C. R. (1990).

disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of

Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Comparison

General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627.

with a credible placebo control. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14,

Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia: Modern problems in pharmacopsychiatry,

22, 141–173.

Heimberg, R. G., Horner, K. J., Juster, H. R., Safren, S. A., Brown, E. J.,

Marom, S., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Aderka, I. M., Weizman, A., &

Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1999). Psychometric properties of

Hermesh, H. (2009). Impact of depression on treatment effective-

the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychological Medicine, 29, 199–212.

ness and gains maintenance in social phobia: A naturalistic study of

Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hope, D. A., Schneier, F. R., Holt, C. S.,

cognitive behavior group therapy. Depression and Anxiety, 26,

Welkowitz, L. A., . . Klein, D. F. (1998). Cognitive behavioral group

therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model

Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 1133–1141.

of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35,

Hofmann, S. G. (2000a). Self-focused attention before and after treatment

of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 717–725.

Ruscio, A. M., Brown, T. A., Chiu, W. T., Sareen, J., Stein, M. B., &

Hofmann, S. G. (2000b). Treatment of social phobia: Potential mediators

Kessler, R. C. (2008). Social fears and social phobia in the USA:

and moderators. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 3–16.

Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.

Hofmann, S. G. (2004). Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social

Psychological Medicine, 38, 15–28.

phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 392–399.

Wells, A., Clark, D. M., Salkovskis, P., Ludgate, J., Hackmann, A., &

Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety

Gelder, M. (1995). Social phobia: The role of in-situation safety

disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications.

behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behavior

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36, 193–209.

Therapy, 26, 153–161.

Hofmann, S. G. (2012). An introduction to modern CBT: Psychological

Wittchen, H. U., & Fehm, L. (2001). Epidemiology, patterns of

solutions to mental health problems. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

comorbidity, and associated disabilities of social phobia. Psychiatric

Hofmann, S. G., & Otto, M. W. (2008). Cognitive-behavior therapy for social

Clinics of North America, 24, 617–641.

anxiety disorder: Evidence-based and disorder-specific treatment techniques.

New York: Routledge.

Hofmann, S. G., & Scepkowski, L. A. (2006). Social self-reappraisal

Address correspondence to Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D., Department of

therapy for social phobia: Preliminary findings. Journal of Cognitive

Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon St., 6th floor, Boston, MA

Psychotherapy, 20, 45–57.

02215; e-mail: .

Hofmann, S. G., & Smits, J. A. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for

adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 621–632.

Received: March 7, 2012

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E.

Accepted: May 9, 2012

(2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV

Available online 16 June 2012

Outline placeholder

Source: http://www.doe-psy.nl/therapiemateriaal/sociale_fobie/Social_Mishap_Exposures.pdf

Australasian Society for Immunology Incorporated PP 341403100035 ISSN 1442-8725 Infection Immunity and Immunogenetics Unit, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Western Australia Can a HIV patient who once progressed to AIDS ever regain a normal immune system on antiretroviral therapy (ART)? Why do some HIV patients beginning ART have an uneventful immune recovery, whilst others develop immune restoration disease? Are the effects of CMV similar in HIV patients, transplant recipients and healthy aging? Why is HCV disease more severe in HIV patients and what determines how HCV patients respond to therapy?

p911 Eggs-tra p914 Under fire: p916 Rebel with a evidence: Scientists NIH scientists say cause: Transgendered they feel punished researcher Ben Barres of proof for fertility for the misdeeds of fights for women in a few colleagues. Threat of pandemic brings flu drug back to life With an effective avian influenza vaccine production capacity to the limit. But Relenza,