Levitra enthält Vardenafil, das eine kürzere Wirkdauer als Tadalafil hat, dafür aber schnell einsetzt. Männer, die diskret bestellen möchten, suchen häufig nach levitra kaufen ohne rezept. Dabei spielt die rechtliche Lage in der Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle.

Consequences of acute stress and cortisol manipulation on the physiology, behavior, and reproductive outcome of female pacific salmon on spawning grounds

Contents lists available at

Hormones and Behavior

Consequences of acute stress and cortisol manipulation on the physiology, behavior,and reproductive outcome of female Pacific salmon on spawning grounds

Sarah H. McConnachie ,, Katrina V. Cook , David A. Patterson , Kathleen M. Gilmour , Scott G. Hinch Anthony P. Farrell , Steven J. Cooke

a Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1S 5B6b Fraser Environmental Watch Program, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Pacific Region, Science Branch, Cooperative Resource Management Institute,School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6c Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, 30 Marie Curie, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 6N5d Department of Forest Sciences and Institute of Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4e Department of Zoology and Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4f Institute of Environmental Science, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1S 5B6

Life-history theory predicts that stress responses should be muted to maximize reproductive fitness. Yet, the

Received 20 December 2011

relationship between stress and reproduction for semelparous salmon is unusual because successfully

Revised 30 April 2012

spawning individuals have elevated plasma cortisol levels. To tease apart the effects of high baseline cortisol

Accepted 2 May 2012

levels and stress-induced elevation of cortisol titers, we determined how varying degrees of cortisol elevation

Available online 8 May 2012

(i.e., acute and chronic) affected behavior, reproductive physiology, and reproductive success of adult femalepink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) relative to different states of ovulation (i.e., ripe and unripe). Exhaus-

tive exercise and air exposure were applied as acute stressors to manipulate plasma cortisol in salmon either

confined to a behavioral arena or free-swimming in a spawning channel. Cortisol (eliciting a cortisol eleva-

tion to levels similar to those in post-spawn female salmon) and metyrapone (a corticosteroid synthesis in-

Oncorhynchus gorbuscha

hibitor) implants were also used to chemically manipulate plasma cortisol. Cortisol implants elevated plasma

Hormone injections

cortisol, and impaired reproductive success; cortisol-treated fish released fewer eggs and died sooner than

fish in other treatment groups. In contrast, acute stressors elevated plasma cortisol and the metyrapone im-

plant suppressed plasma cortisol, but neither treatment significantly altered reproductive success, behavior,

or physiology. Our results suggest that acute stressors do not influence behavior or reproductive outcome

when experienced upon arrival at spawning grounds. Thus, certain critical aspects of salmonid reproductioncan become refractory to various stressful conditions on spawning grounds. However, there is a limit to theability of these fish to tolerate elevated cortisol levels as revealed by experimental elevation of cortisol.

2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

an emergency response and animals attempt to regain

Considerable evidence supports the notion that stress can impair

allostasis (). Yet, much of the existing

the reproductive outcome of a wide range of vertebrates, including

work on chronic stress/glucocorticoid elevation is focused on the

birds ), reptiles

long-term consequences for animals during non-reproductive pe-

riods rather than immediately before or during reproduction. For ex-

), and fish ). The

ample, many toxicological studies demonstrate direct long-term

acute stress response and associated elevation of glucocorticoids is

reproductive impairments (e.g., suppression of reproductive hor-

believed to be adaptive, while chronic elevation of glucocorticoids

mones) associated with emergency resource reallocation to mainte-

can have various negative tertiary effects, including impaired im-

nance and survival (e.g., reviewed in see

mune function and fitness whenever resources are directed towards

also ).

Furthermore, most of these studies consider iteroparous species (i.e.

repeat breeders), which have the life-history option of delaying a

⁎ Corresponding author.

reproductive event when challenged.

E-mail addresses: (S.H. McConnachie),

In contrast, semelparous species usually cannot delay the repro-

(K.V. Cook), (D.A. Patterson),

ductive event because they invest in reproduction only once in a life-

(K.M. Gilmour), (S.G. Hinch),(A.P. Farrell), (S.J. Cooke).

time. For semelparous fishes such as Pacific salmonids (Oncorhynchus

0018-506X/$ – see front matter 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

spp.), some argue that the spawning date is genetically fixed, which

successfully blocks cortisol synthesis in fish in the short-term

implies that it cannot be altered by external stressors

Curiously, virtually nothing is known about whether exposing

but has rarely been used with a cocoa butter carrier (but see

semelparous Pacific salmonids to stress on spawning grounds influ-

). Rainbow trout (O. mykiss), a congeneric of pink

ences their behavior and reproductive success. Yet, these fish routine-

salmon, weighing approximately 150 g were anesthetized with ben-

ly encounter many stressors that trigger a cortisol response as they

zocaine (0.05 mg ml−1 water; p-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester;

approach their spawning date, suggesting that the acute stress re-

Sigma E1501, Sigma-Aldrich) and given an IP injection of metyrapone

sponse remains active during the reproductive period. For example,

mixed in heated liquid cocoa butter (200 mg kg−1 fish in l ml cocoa

plasma cortisol rises when fish encounter hydraulic challenges and

butter kg−1 fish); upon injection into the fish, the cocoa butter rapid-

elevated water temperature during the spawning migration (

ly cools to a thick paste, providing a slow-release metyrapone im-

). Furthermore, a progressive increase

plant. After 1 and 5 days, fish were subjected to 1 min of air

in baseline plasma cortisol levels of unknown etiology occurs as salm-

exposure as an acute stressor, and a blood sample was withdrawn

on swim to the spawning grounds

by caudal puncture 30 min later for assessment of plasma cortisol

levels. The expectation was that this 30-min delay would be sufficient

cortisol concentrations rise from 25 ng ml−1 in pink salmon (O.

for the maximum or near maximum rise in plasma cortisol level to be

gorbuscha) at river entry (), to 350 ng ml−1 on

arrival at the spawning ground (female sockeye salmon [O. nerka];), and 1287 ng ml−1 when the fish become mor-

Weaver Creek spawning channel

ibund (female sockeye salmon; ). Thus, an acutestressor can elevate plasma cortisol against a background of progres-

All field experiments were conducted at the Weaver Creek

sively increasing plasma cortisol levels during the spawning

spawning channel located in British Columbia, Canada (see

for detailed information). Each experiment involved

A stressed state should generally be incompatible with reproduc-

groups of naive fish (i.e., fish were not reused among experiments).

tion and, based on life-history theory, one could postulate that the

The artificial channel, 2.93 km long and 6.1 m wide, is composed of

cortisol stress response of semelparous salmon should be muted, or

a cobble (1.2–7.6 cm) substrate and has a consistent water depth of

physiologically irrelevant, during this period (

25–30 cm. Fish densities and flow conditions were monitored

) to mitigate any potential negative effects of cortisol

throughout the spawning period and manually operated gates were

elevation above the (high) baseline levels on spawning grounds.

used to regulate fish movements into the spawning channel

Thus, we postulate that reproductive drive in a semelparous salmon

(). Experiments were timed to coincide with peak

species will outweigh any cortisol-mediated mating inhibition.

pink salmon spawning activity in early October 2009.

Acute, stress-related increases in plasma cortisol suppress the normalincreases in plasma sex hormone concentrations for Pacific salmon

Reproductive physiology on arrival

during early phases of upriver migration (However,increases in plasma cortisol during migration are regarded as adap-

On arrival at the spawning channel in early October, female pink

tive and necessary for salmon to be able to return to their natal

salmon were individually removed from the raceway via dip net

streams and spawn (Complicating matters is

and immediately placed in a trough supplied with flow-through

the fact that spawning Pacific salmon also undergo senescence,

water from the raceway. Fish were categorized as either "unripe"

which alters many physiological processes, including hormone regu-

(N = 52, unovulated, where eggs are still confined to intact ovaries)

lation To address

or "ripe" (N = 60, ovulated, where eggs have been released into the

these issues, we experimentally determined how short-term changes

body cavity and gentle abdominal pressure near the vent easily ex-

in and experimental manipulation of plasma cortisol influenced the

pels eggs) and a blood sample was collected via caudal puncture

reproductive physiology, behavior, and spawning outcome of wild fe-

(2 ml blood sample; collected using 3 ml vacutainer and 1.5 in.,

male pink salmon (O. gorbuscha). We administered cortisol implants

18 ga needle, lithium heparin; Becton Dickson, NJ) within 30 s

and predicted that plasma cortisol elevation, lasting between 2 and

(Within 3 min the fish were released back into

5 days, would negatively affect reproductive behavior (e.g., less time

the spawning channel. Blood samples were stored in an ice-water

spent guarding eggs or fighting for a mate), physiology (i.e., suppres-

slurry and centrifuged (5 min at 10,000 g) within 45 min, after

sion of reproductive hormones), and outcome (i.e., number of eggs

which the plasma was frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately. Samples

released). We also predicted that the response to acute stressors

were subsequently stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

(i.e., exhaustive exercise or air exposure) would be muted in semel-

In addition, subsets of ripe (N= 6) and unripe (N= 12) salmon

parous salmon and would not alter these same responses. Conversely,

were given an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of either cortisol (hydrocor-

an intraperitoneal (IP) implant of metyrapone, which blocks the last

tisone 21-hemisuccinate; Sigma H4881, Sigma-Aldrich; 110 mg kg−1

step of glucocorticoid synthesis, was expected to lower plasma corti-

fish in 50 ml melted cocoa butter kg−1 fish; ) to el-

sol levels () and retard reproduction and senes-

evate cortisol levels for a short period (i.e., 2 to 5 days), or metyrapone

cence. To our knowledge, hormone manipulations of this type had

(200 mg kg−1 fish; 1 ml cocoa butter kg−1 fish) to block glucocorticoid

not before been performed on senescing Pacific salmon.

synthesis (), before being placed in individual,opaque, experimental chambers ( 50 l) situated on the bank of the

Materials and methods

channel and equipped with flow-through water. Fish were leftundisturbed for approximately 24 h, after which they were individually

Metyrapone validation

removed and blood was sampled immediately via caudal puncture.

All fish were handled in accordance with the guidelines of the Ca-

Longevity and reproductive status study

nadian Council on Animal Care (Carleton University, B09-12; Univer-sity of Ottawa, BL-228). A pilot laboratory experiment was carried out

On October 6th and 7th 2009, 120 unripe pink salmon that had

to determine the effectiveness of metyrapone (2-methyl-1, 2-di-3-

voluntarily entered the raceway were marked with unique individual

pyridyl-1-propanone; Sigma 85625, Sigma-Aldrich) at blocking corti-

Peterson disk tags placed in the dorsal musculature. The tags could be

sol synthesis when delivered in a cocoa butter implant. Metyrapone

read on free-swimming fish with binoculars, which allowed the fish

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

to be observed without any disturbances. Fish were randomly

fish was on the receiving end of an aggressive act (both were

assigned to one of six treatment groups (N = 20 per treatment

summed and divided by total observation minutes, and aggression re-

group): a) control fish (only tagged); b) sham injection-controls

ceived was subtracted from aggression given to yield an overall ag-

(tagged and given an IP injection of 50 ml kg−1 melted cocoa butter);

gression score). The daily duration of behavioral observations on

c) cortisol-treated (as described above); d) metyrapone-treated (as

each fish (i.e., 10 min) was consistent with other studies

described above); e) chased (acutely stressed by 3-min of being

and is believed to be representative of longer time periods

"chased" by hand around a circular tank supplied with flow-through

given the reasonable predictability and stability of behavioral reper-

channel water); and f) air-exposed (as in (e), followed by 1 min of

toires for this species. After 4 days, the fish were collectively culled

air exposure to increase the severity of the acute stressor). After-

in a process lasting b 10 min; fish were killed by cerebral percussion.

wards, fish were immediately released into the spawning channel

After immediate blood sampling, the percentage of eggs released

and closely monitored during daylight hours so that moribund or

was estimated (as described above).

dead fish could be collected daily.

Longevity in the spawning channel following release (i.e. time until

death after arrival) was calculated using the methods outlined inFork length, total mass, gonad mass, epidermal

Plasma glucose and cortisol concentrations were measured as in-

coverage by fungus, and general condition also were documented. Re-

dicators of stress Briefly, plasma glucose

productive status was reported as the percentage (%) of eggs released

values were determined using a YSI 2300 STAT Plus glucose analyzer

by each individual. The relationship between percentage of eggs

(YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, Ohio). Plasma cortisol levels were measured

remaining relative to percentage of eggs initially expected was deter-

using a commercial ELISA kit (Neogen Corporation # 402710, Lexing-

mined following the methods of . Briefly, the antic-

ton KY). For cortisol, the assay has 47% cross-reactivity with the drug

ipated initial gonad mass was determined from a known relationship

prednisolone, which would not be present in the samples.

between body mass and gonad mass established for a separate group

The assay also has 15% cross-reactivity with cortisone and 11-

of mature, unripe pink salmon sampled from the spawning channel

deoxycortisol. The analytical sensitivity (B/B

(N= 21; gonad mass= 10.1·body mass −297.9, R2=0.80, P=0.005).

0, 80%) for the cortisol

assay was at 0.04 ng ml−1. Testosterone and 17β-estradiol are both

Eggs were weighed and counted in whole ovaries and a linear body

major reproductive hormones and plasma concentrations of these hor-

mass to fork length relationship, together with a linear fork length to

mones also were measured by ELISA kits (Neogen Corporation,

gonad mass relationship, was used to interpolate the expected egg

, catalog numbers: 402110, 402510). Testosterone and

mass before ovulation for the experimental fish. Many fish had

17β-estradiol were extracted from plasma samples using ethyl ether

spawned all of their eggs (100% success), but any eggs remaining

according to the kit manufacturer's protocols. The assay manufacturer

were weighed first as five groups of 10 eggs, with any eggs remaining

states that the estradiol assay does not cross-react with any other estro-

thereafter being weighed collectively. Individual egg mass is known to

gens. Analytical sensitivity (B/B

be uniform within an individual (D. Patterson, personal communica-

0, 80%) was at 0.03 ng ml− 1. According

to the manufacturer, the testosterone assay is 100% cross-reactive

tion), and so this method provided an accurate estimate of the number

with dihydrotestosterone and the analytical sensitivity (B/B

of eggs retained by each fish without having to count every egg.

was at 0.006 ng ml−1. Cortisol, glucose, testosterone, and 17β-estradiol were assayed in duplicate at appropriate dilutions. Inter- and

Spawning behavior in enclosures

intra-assay variability was b10% for all assays. More detailed descrip-tions of the analytical techniques can be found in

Behaviors were studied in unripe and ripe salmon held in enclo-

sures that had been constructed within the spawning channel. Ablood sample (as described above) was withdrawn from 30 salmon(6 treatment groups as above; N = 5 for each treatment group) in

Statistical analysis

the raceway before placing them in a holding tank for transfer to asection of the spawning channel that housed a net-pen (2 m wide

Results from the metyrapone pilot study were analyzed using a

by 15 m long; constructed out of Vexar rigid mesh fencing; Master-

two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether cortisol

net, Mississauga, Ontario). Fish were treated according to their exper-

values varied by treatment and time. Results from the cortisol and

imental group before being placed into the enclosure. Twenty "ripe"

metyrapone validation study before and after 24 h were compared

male pink salmon (i.e. males that released sperm when squeezed

using two-way repeated measures ANOVA models with time and

gently near the vent) had been placed into the net-pen 12 h earlier.

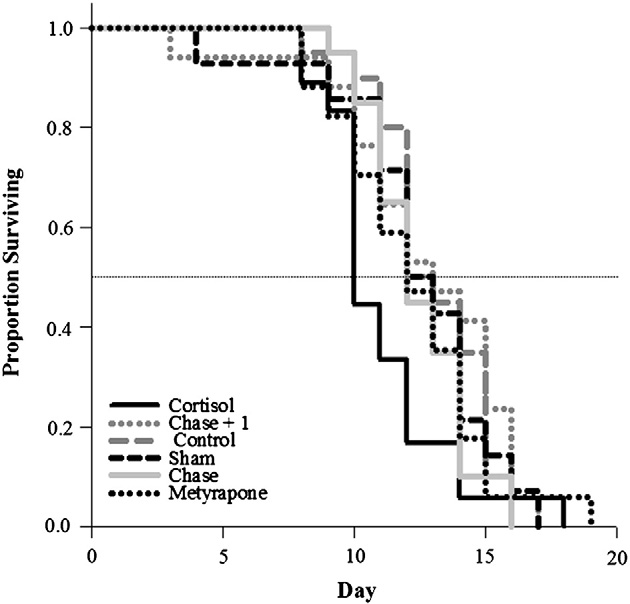

treatment as effects. For the channel experiment, longevity among

Fewer males were placed in the pen than females to facilitate compe-

treatment groups was compared using a log-rank survival analysis

tition among females. Two trials were completed for unripe salmon in

to 50% mortality. The percentage of eggs released by each fish was

early October 2009, and two trials were completed for ripe fish in late

averaged within groups and compared using a one-way ANOVA. For

October 2009.

the enclosure experiments, all hormone and blood physiology values

Behavioral observations were carried out for 10 min daily on four

and behavioral metrics were compared before and after 4 days using

consecutive days. The order of observing each fish was randomized

two-way repeated measures ANOVA models with time and treatment

daily. Reproductive behaviors of pink salmon are well known, and

being the independent variables. Time until territory establishment

are similar to behaviors displayed by other semelparous Pacific salm-

was determined using log-rank survival analyses. The percentage of

on Females prepare their

eggs released by each fish was averaged for each treatment group and

nesting area, fend off intruders from their territory through aggres-

compared using a one-way ANOVA. Tukey's post-hoc tests were

sive action, and spend time with males to ensure fertilization occurs.

employed following significant one-way ANOVAs to determine differ-

We recorded on what day fish established a territory, how much time

ences among groups (where p b 0.05). The assumptions of equality of

the fish spent holding that territory (represented as a percent, aver-

variances and normal distribution were tested for all analyses and

aged over days on territory), what percentage of their time females

relevant transformations applied where assumptions could not be met.

spent with males (averaged across days on an established territory),

Percentage data were arcsine transformed prior to analysis. Where trans-

the number of nest construction digging behaviors that occurred (av-

formation of the data was not possible or effective, non-parametric anal-

eraged across days spent on a territory), how many times a fish made

yses were performed. All analyses were conducted using JMP, version

an aggressive display towards a conspecific, and how many times that

8.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The level of significance (α) for all

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

tests was assessed at 0.05. All data are presented as mean ±standard

error unless otherwise noted.

Initial blood hormone and glucose values of ripe and unripe pink salmon(Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) removed from the Weaver Creek raceway in October,2009, presented as mean (± SE). N = 52 for unripe fish and N = 60 for ripe fish. All

data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test, except for cortisol (*), whichwas analyzed using log-transformed data in a one-way ANOVA.

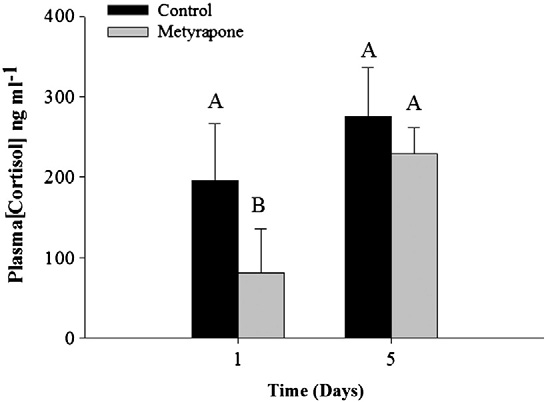

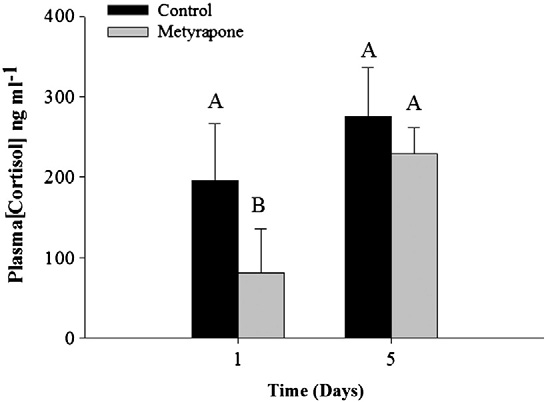

Effectiveness of metyrapone

Metyrapone-treated rainbow trout subjected to an acute stressor

exhibited significantly lower plasma cortisol concentrations than

Glucose (mmol l−1)

sham-treated fish 1 day following treatment (two-way ANOVA Time

Cortisol (ng ml−1)*

Estradiol (ng ml−1)

effect: F = 7.8, df = 1, p = 0.02; but not after 5 days (Treat-

Testosterone (ng ml− 1)

ment effect: F = 3.1, df = 1, p = 0.1; Interaction: F = 4.7, df = 3,p = 0.03; ). Therefore, we assumed that pink salmon would ex-perience a short-term depression of plasma cortisol during acute

measures ANOVA: Treatment effect: F= 1.0, df =1, p b 0.001; Time:

stress (i.e., for at least 24 h but not as long as 5 days) and used

F = 34, df =1, pb 0.001; Interaction: F=5.4, df=3, pb 0.001;

cocoa butter as a vehicle for metyrapone delivery.

Plasma glucose values increased 24 h after either treatment (Treatmenteffect: F =5.1, df =1, p= 0.3; Time: F =6.8, df =1, p= 0.02; Interaction:

Raceway blood physiology and hormone validations

F= 2.2, df =3, p=0.03; Estradiol was unaffected by either treat-ment (Treatment effect: F=0.69, df= 1, p=0.4; Time: F= 0.90, df =1,

Reproductive hormone titers were indicative of whether pink

salmon in the spawning channel were ripe or unripe (). Plasma estradiol and testosterone were both signifi-cantly lower in ripe fish (estradiol: F = 70, df = 1, p b 0.001; testoster-one: F = 25, df = 1, p b 0.001; However, plasma cortisolconcentrations were similar (one-way ANOVA, F = 0.31, df = 1,p = 0.6; and plasma glucose concentrations were higher inripe fish (one-way ANOVA, F = 13, df = 1, p b 0.001; ) for arriv-ing pink salmon.

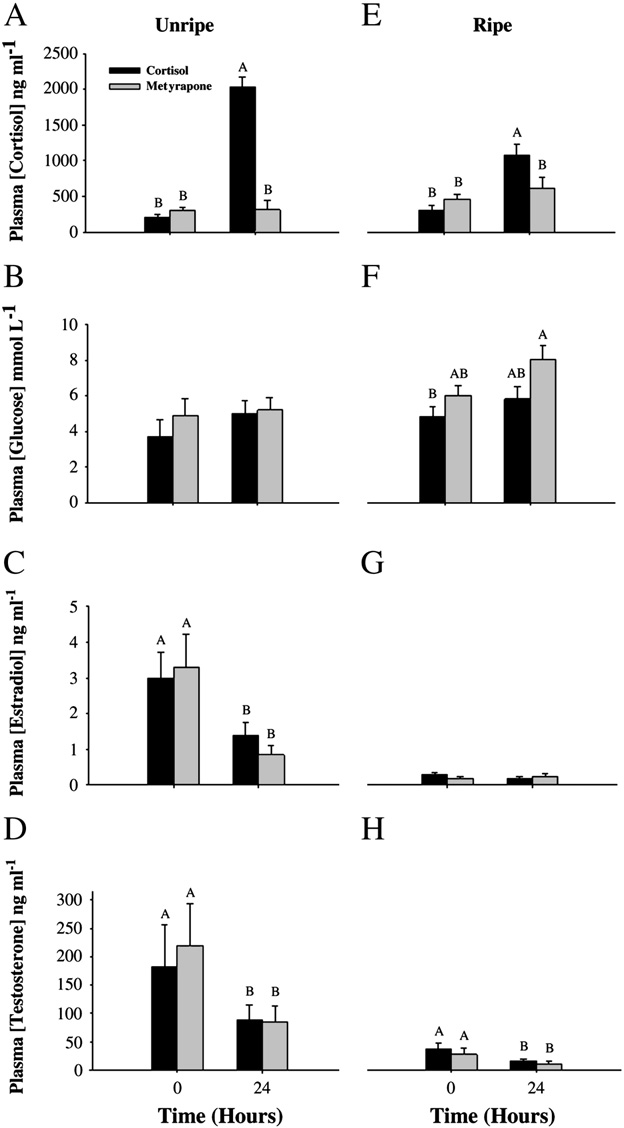

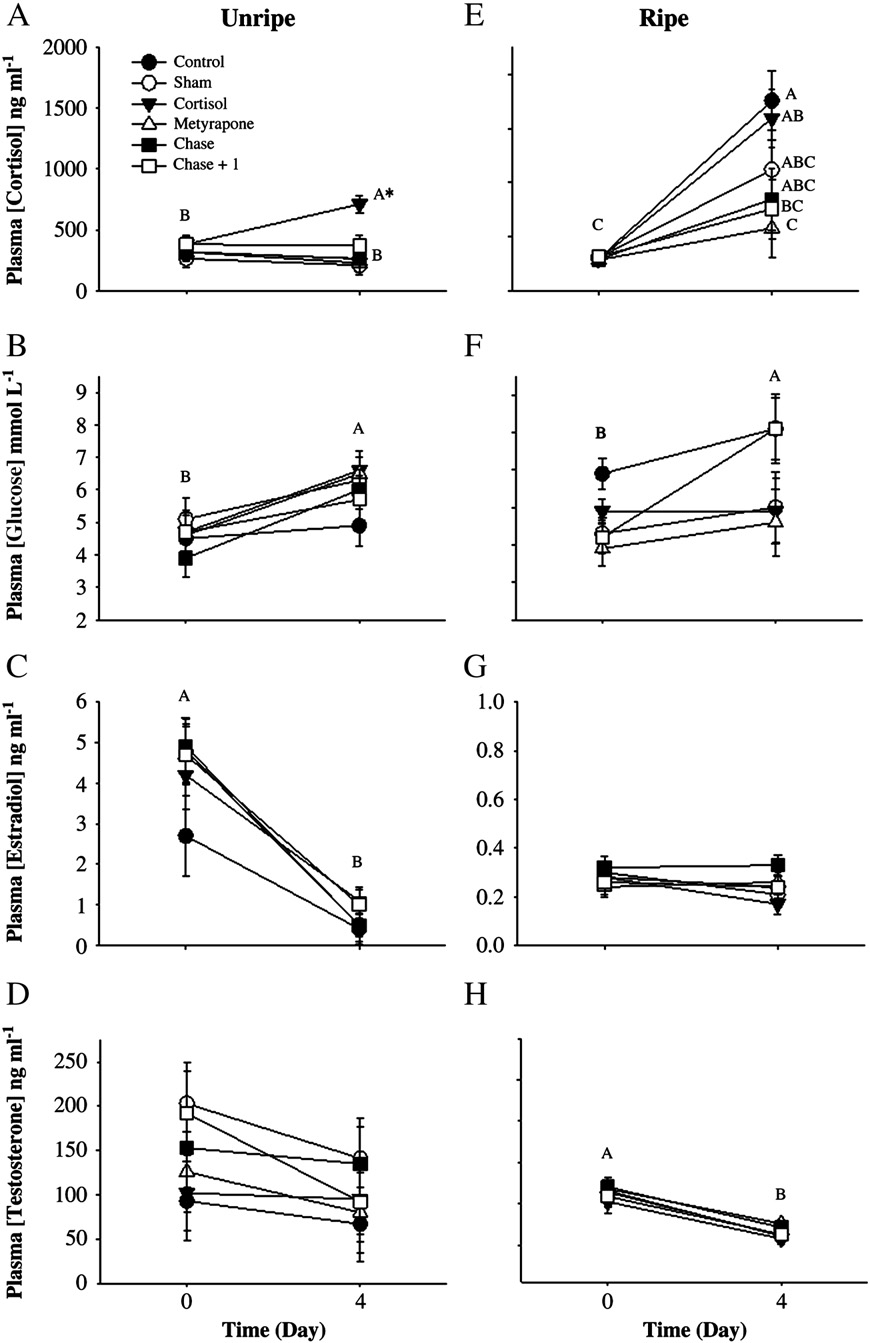

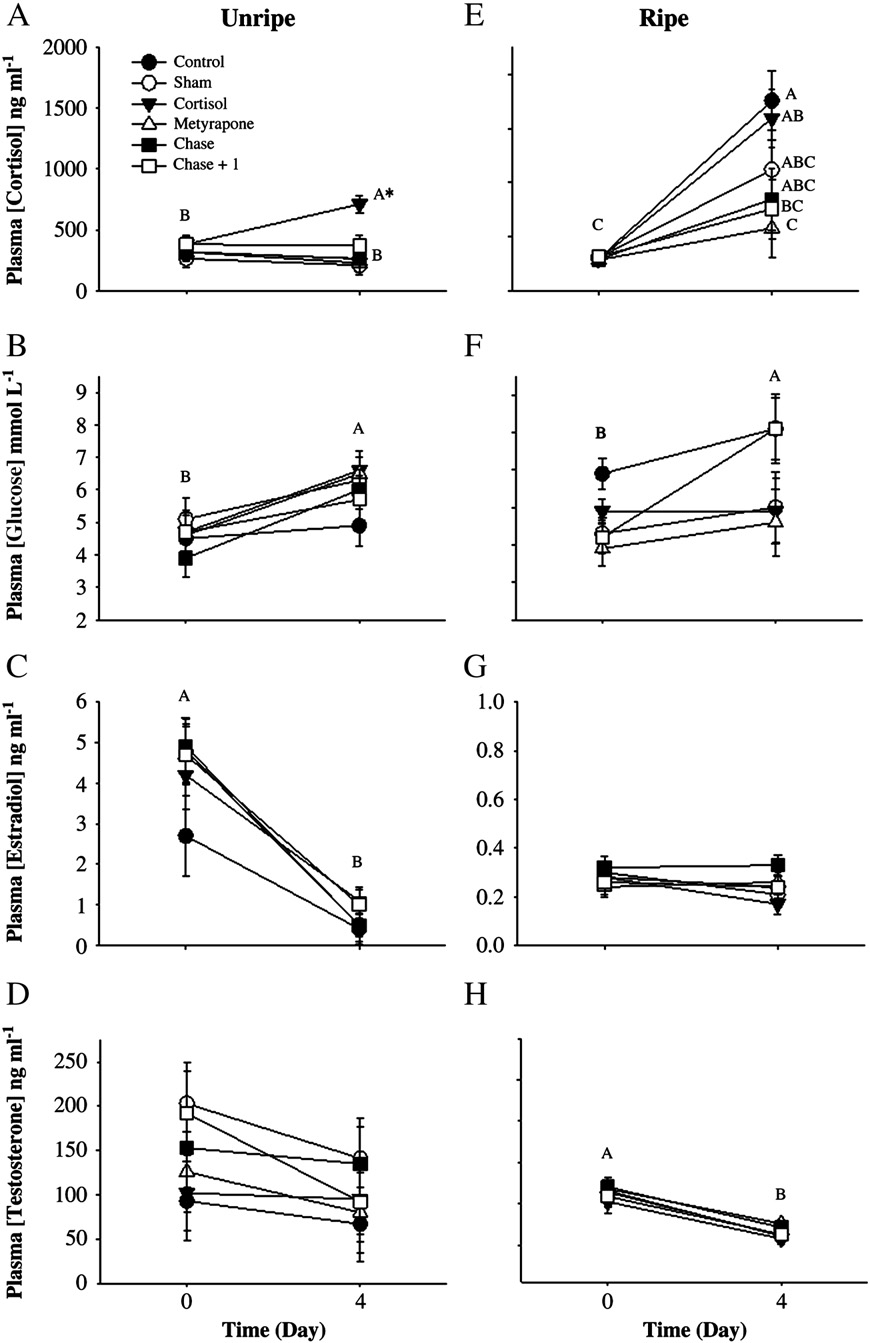

For unripe fish held in isolation chambers, cortisol implants signifi-

cantly elevated plasma cortisol by 10-fold, but metyrapone implantshad no effect on circulating cortisol levels after 24 h (two-wayrepeated-measures ANOVA: Treatment effect: F=55, df= 1, p b 0.001;Time: F=70, df= 1, p b 0.001; Interaction: F=15, df=3, pb 0.001;Plasma glucose was unchanged 24 h after either treatment(Treatment effect: F=0.69, df =1, p =0.4; Time: F= 0.90, df =1,p= 0.4; Interaction: F= 0.39, df =3, p =0.9; ). Plasma concentra-tions of both estradiol (Treatment effect: F =0.8, df= 1, p =0.8; Time:F= 8.5, df =1, p =0.02; Interaction: F=1.5, df= 3, p= 0.3; C)and testosterone (Treatment effect: F=0.13, df= 1, p =0.7; Time:F= 5.7, df =1, p=0.04; Interaction: F=1.7, df= 3, p =0.2; D) de-creased 24 h after either treatment.

For ripe fish held in isolation chambers, the cortisol implant again

increased plasma cortisol values, but the response was attenuated com-pared with that of unripe fish E). Plasma cortisol concentrationwas not affected by the metyrapone implant (two-way repeated-

Fig. 2. A–H. Summary of pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) plasma hormone and

Fig. 1. Mean (± SE) cortisol values for control and metyrapone-treated rainbow trout

glucose values for unripe (A–D) and ripe (E–H) fish both before and 24 h after treat-

(Oncorhynchus mykiss) subjected to an air-exposure stressor either 1 or 5 days after

ment with cortisol or metyrapone. Values are stated as mean (± SE). Dissimilar letters

treatment with metyrapone. Data were log-transformed and analyzed using a two-

denote significant differences among treatment groups and time periods (Tukey–

way ANOVA. Dissimilar letters denote a significant difference between treatment

Kramer HSD test, p b 0.05). N = 6 for each treatment for unripe fish; N = 12 for ripe

groups and/or time periods (Tukey–Kramer HSD test, p b 0.05). Sample sizes are as fol-

fish. All Ranked Sum data were analyzed using a two-way repeated-measures

lows: 1 day: control = 2, metyrapone = 5. 5 days: control = 4, metyrapone = 4.

ANOVA, with time and treatment as independent variables.

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

p= 0.4; Interaction: F=1.2, df= 3, p =0.3; Plasma testosteronewas decreased 24 h after both treatments (Treatment effect: F=0.83,df= 1, p= 0.4; Time: F =21, df =1, pb 0.001; Interaction: F=0.27,df= 3, p= 0.6;

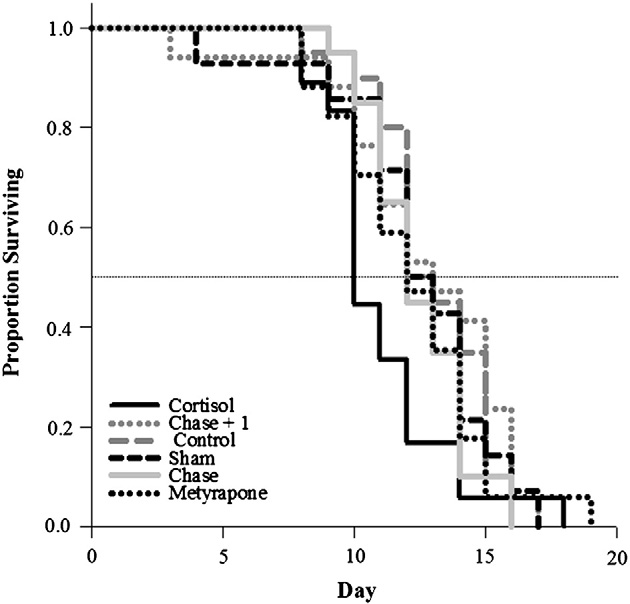

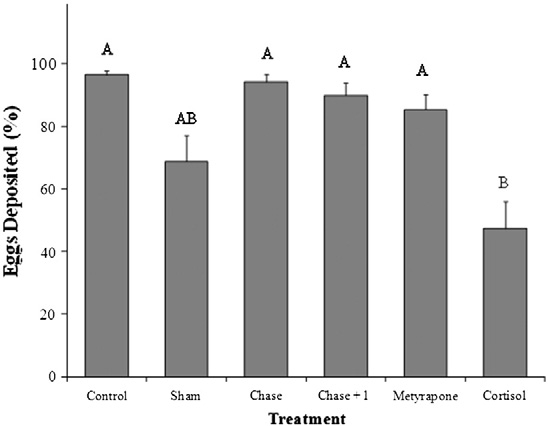

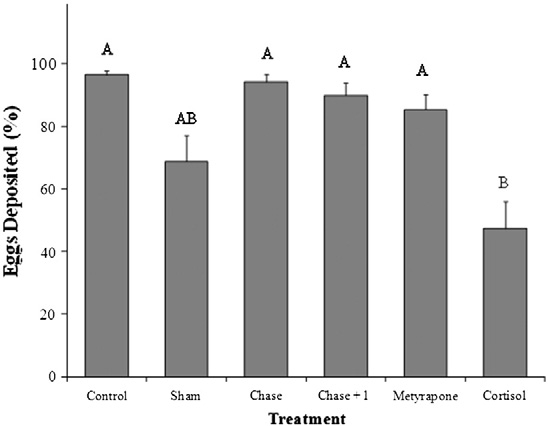

Longevity and reproductive study

Pink salmon treated with cortisol exhibited reduced longevity rel-

ative to all other treatment groups (log-rank survival time to 50%mortality; λ2 = 13.1, df = 5, p = 0.02; ). Cortisol-treated fishalso released fewer eggs during their time in the channel comparedwith all other treatment groups except the sham group [47% forcortisol-injected; 69% for sham-treated; >85% for all other groups(one-way ANOVA, F = 13, df = 5, p b 0.001; )].

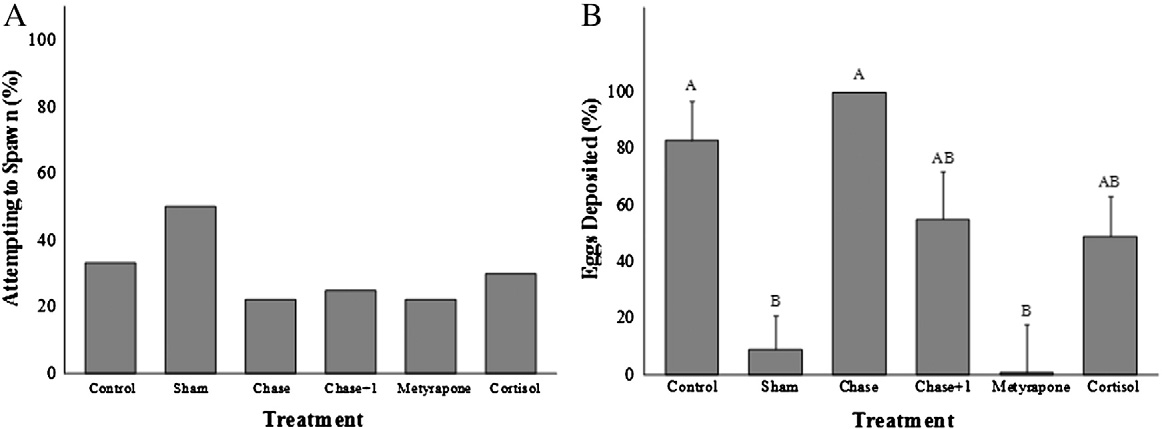

Enclosure experiment: reproductive status

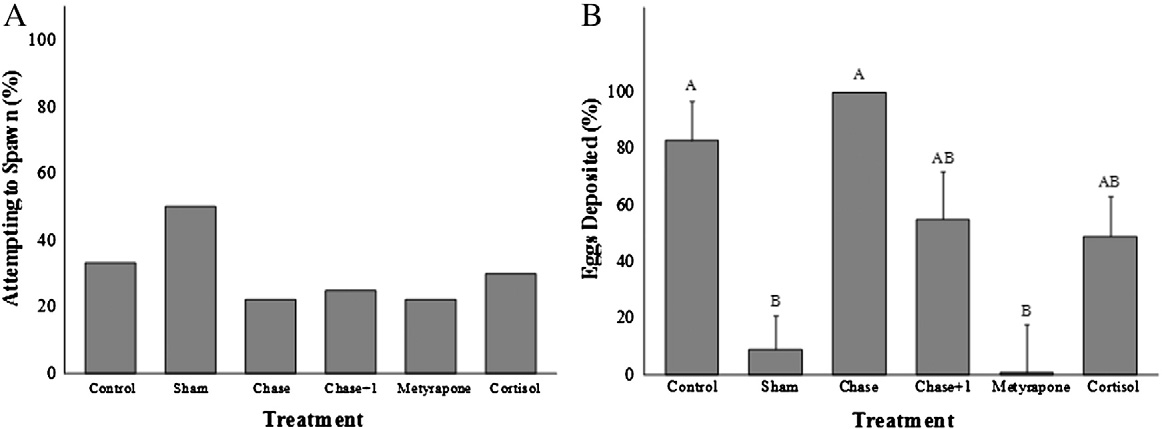

Fig. 4. A comparison across treatment groups (see text for details of treatment groups)of the percentage (%) of total possible eggs deposited by pink salmon (Oncorhynchus

Treatment with cortisol, metyrapone or acute stress did not influ-

gorbuscha) in the Weaver Creek spawning channel during early October, 2009. All

ence the extent to which fish ripened during the experiment

data were transformed into ArcSine (square root) values before analysis. Samplesizes were as follows; chase and control = 20, cortisol = 18, chase + 1 min air exposure

. For those fish that did ripen during the enclosure experiment,

and metyrapone = 17 and sham = 14. Dissimilar letters denote significant differences

differences in egg release (%) were observed (Wilcoxon Rank Sum;

among treatment groups (Tukey–Kramer HSD test, p b 0.05).

λ2=11.2, df=5, p=0.04; . Control and chased fish releasedmore than 80% of their eggs, chase + 1 min air exposure and cortisol-treated fish released approximately 50% of their eggs, and metyrapone

Time: F = 72, df = 1, p b 0.001; Interaction: F=0.6, df=5, p=0.7;

and sham-treated fish released the fewest eggs (b10%). For ripe fish,

C), whereas plasma testosterone concentrations remained

there were no statistically significant differences in egg release

unchanged over the 4 day experimentation period (Treatment effect:

among treatment groups (data not shown). However, cortisol-treated

F = 1.1, df = 1, p = 0.4; Time: F = 3.3, df = 1, p = 0.08; Interaction:

fish released 50% of their eggs, whereas all other treatment groups

F = 0.3, df = 5, p = 0.9; D).

released >70% of their eggs.

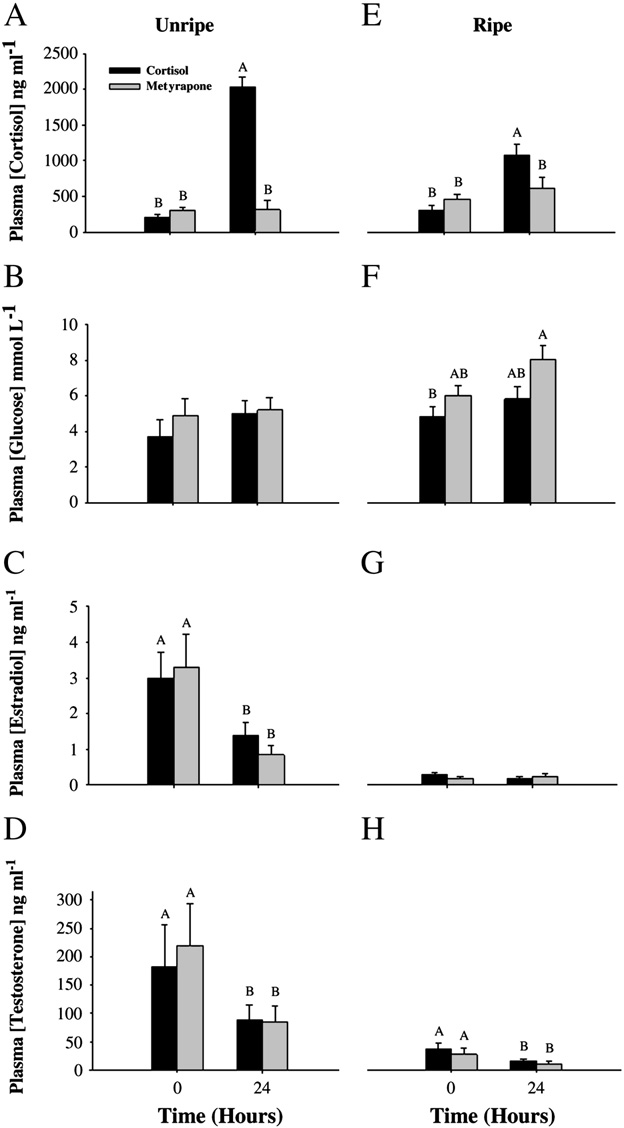

For ripe fish, plasma cortisol levels varied across treatment groups

after 4 days Control fish exhibited the highest levels (1756±

Enclosure experiment: hormone profiles

274 ng ml−1), and cortisol-treated fish displayed similar concentrations

(averaging 1592 ±207 ng ml−1). Values were similar among sham-

Among unripe fish, cortisol-treated fish exhibited elevated cortisol

treated (1118 ±211 ng ml−1), chased fish (846±289 ng ml−1), and

concentrations 4 days following treatment (two-way repeated-

chased+ 1 (757 ±186 ng ml−1) fish, whereas the lowest value (577±

measures ANOVA: Treatment effect: F = 4.6, df = 1, p = 0.002; Time:

193 ng ml−1) was observed in metyrapone-treated fish (two-way

F = 0.4, df = 1, p = 0.9; Interaction: F = 2.5, df = 5, p = 0.04; .

repeated-measures ANOVA: Treatment effect: F=2.7, df =1, p =0.03;

Plasma glucose concentration increased in all fish during the 4 day ex-

Time: F= 55, df =1, pb 0.001; Interaction: F=3.2, df=5, p=0.01;

periment (Treatment effect: F = 0.7, df = 1, p = 0.6; Time: F = 15.6,

E). Plasma glucose concentrations increased during the 4 day peri-

df= 1, p b 0.001; Interaction: F=0.6, df=5, p=0.7; B). Plasma

od, across treatments (Treatment effect: F=1.7, df= 1, p=0.1; Time:

estradiol levels decreased (Treatment effect: F = 0.5, df= 1, p = 0.8;

F= 5.4, df =1, p= 0.02; Interaction: F =0.93, df =5, p= 0.5; Plasma estradiol levels were low and did not change (Treatment effect:F= 1.2, df=1, p=0.3; Time: F=2.5, df =1, p =0.1; Interaction:F= 0.7, df =5, p =0.6; , whereas plasma testosterone concentra-tions decreased after 4 days (Treatment effect: F= 0.4, df= 1, p= 0.8;Time: F= 91, df= 1, p b 0.001; Interaction: F=0.2, df=5, p=0.9;H).

Enclosure experiment: behavior observations

Among unripe fish, treatment did not influence the rate of territory

establishment (log-rank survival analysis; λ2=2.4, df=5, p=0.8).

Based on behavioral observations for fish on territories, cortisol-treated fish spent 10% less time holding their territory comparedwith controls (one-way ANOVA: F = 12, df = 5, p = 0.03; Addi-tionally, cortisol-treated fish were less aggressive and experiencedmore aggressive acts by conspecifics (F=13, df=5, p=0.04;Among ripe fish, no differences were noted for territory estab-lishment (log-rank survival analysis; λ2=4.0, df=5, p=0.5). In addi-tion, no behavioral differences were observed among the treatmentsgroups ().

Fig. 3. Log-rank survival analysis to 50% mortality in each treatment group (see text for

By experimentally elevating plasma cortisol in unripe fish for be-

details of treatment groups), comparing longevity among pink salmon (Oncorhynchus

tween 2 and 5 days with a cortisol in cocoa butter implant, we negative-

gorbuscha) in the Weaver Creek spawning channel. Sample sizes were as follows:chase and control = 20, cortisol = 18, chase + 1 and metyrapone = 17 and sham = 14.

ly impacted the longevity, reproductive behavior, and reproductive

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

Fig. 5. (A and B). Figure A presents the percentage of pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) that became ripe during the behavior trials and thus were able to spawn during theenclosure experiment. Figure B presents the percentage of total eggs available (%) that were deposited during the 4 day trials by ripened fish across treatment groups. Sample sizeswere as follows: chase = 1/9, chase + 1 = 2/8, control = 3/9, cortisol = 3/10, metyrapone = 2/9, sham = 4/8. All data were transformed into ArcSine (square root) values beforebeing analyzed. Dissimilar letters denote significant differences among treatment groups (Tukey–Kramer HSD test, p b 0.05).

outcome of pink salmon on their spawning grounds. Conversely, acute

Nonetheless, collectively these data are consistent with the notion

stressors that also presumably elevated plasma cortisol, namely exercise

that semelparous salmon may be resilient to the effects of stress hor-

and air exposure, did not affect reproductive outcomes in either ripe or

mones during the final phases of reproduction

unripe fish. These results demonstrate that a sustained elevation of plas-

). However, in the case of Pacific salmon, it is unclear

ma cortisol carries significant reproductive costs for semelparous salmon

when such a transition takes place during the migration. In main-

on their spawning grounds (despite their high baseline cortisol levels),

stream riverine habitats, fish mount a cortisol response to a stressor

but that temporary elevations may not. In an ecologically relevant

and cortisol does, indeed, result in suppression of reproductive

context, events that could elicit a prolonged stress response that might

hormone titers ). Yet, our data indi-

last 2–5 days include periods of high water temperature (

cate that, upon arrival at spawning grounds, reproductive hormones are

), seasonally high (or low) river discharge ),

not altered by either certain acute stressors that are expected to elevate

river obstructions or regions that are hydraulically complex (

plasma cortisol levels (see below) or experimental cortisol manipulation.

), or disease ). In contrast, very short-

Because we did not observe any differences between ripe and unripe fish

term stressors, which might include fisheries interactions, failed preda-

with respect to the influence of cortisol elevation on hormone titers, the

tion events, and antagonistic interactions with conspecifics just prior to

onset of resistance to elevated cortisol appears to occur prior to ovulation,

or during spawning may result in fewer effects on reproduction.

a point that warrants investigation in a further study. The transition maybe associated with the decline from stable levels of reproductive hor-

Cortisol manipulation and reproductive hormones

mones as the fish move into an ovulated state. During ovulation, thereis a critical need to increase 17α-hydroxy-20 β-dihydroprogesterone

In a variety of fish species, elevation of glucocorticoids results in de-

(17α, 20β-P) to complete reproduction because this

creased reproductive hormone concentrations (see review by

hormone induces sexual maturation necessary for the ovulation process,

), which in iteroparous fish can lead to a postponed

whereas estradiol and testosterone mediate maturation and ovulation

reproductive event. Additionally, a stressful reproductive environment

(e.g., fish exposed to bleached kraft pulp mill effluent) negativelyimpacts reproductive fitness in various ways

Channel longevity and reproductive success

). In semelparous Pacific salmonexposed to a natural hydraulic challenge during their reproductive

Cortisol-treated fish exhibited decreased longevity and high egg

migration up the Fraser River system in BC (at the Hell's Gate fishway,

retention during the channel experiment, despite our finding that

in the Thompson Canyon, BC, ),

cortisol treatment did not change reproductive hormone titers.

reproductive hormone titers (i.e., 11-ketotestosterone, estradiol and

Therefore, chronic cortisol elevation on spawning grounds negatively

testosterone) fall dramatically while cortisol levels increase. Further

influences reproductive function and success. Even though egg re-

upstream, where the river is less challenging and perhaps less than

lease by metyrapone- and sham-treated fish during the unripe enclo-

1 day later in the migration, baseline values of cortisol are restored

sure experiment was reduced when compared to other treatment

( 100 ng ml−1) and reproductive hormones return to their elevated

groups, overall these fish still released the majority of their eggs and

levels Yet prior to the present study, the potential

longevity was comparable to control groups. As such, even if the

interactions between cortisol and reproductive hormone oscillations

cocoa butter implant did prevent some egg release in the sham, corti-

had not been investigated in terms of impacts on behavior at spawning

sol, and metyrapone treatments (see discussion below), the existence

grounds and reproduction for a semelparous species. The raceway

of differences among these treatments lends support to the notion

blood profiles and hormone validation data collected in the present

that the driver of the differences was of a physiological nature rather

study indicated that, even though cortisol titers in cortisol-treated

than an artifact of the use of cocoa butter.

fish were increased to levels observed in senescing salmon (

This suite of findings is particularly important because fisheries

managers are concerned with the largely unexplained phenomenon

cortisol treatment did not alter reproductive hormone titers in either

of "pre-spawn mortality"—fish that die on spawning grounds either

unripe or ripe fish.

without spawning or with significant egg retention

It is important to recognize that the experimental elevation of cor-

The eggs of such fishes are often still viable (

tisol titers with IP implants is not itself a stress response, but instead

so it appears that other factors are inhibiting reproductive be-

results in elevated cortisol that is consistent with a stress response.

havior and/or are advancing senescence. In a study of sockeye salmon

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

Fig. 6. (A–H). Blood hormone and glucose values of unripe (A–D) and ripe (E–H) pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) before experimentation and 4 days after treatment (seetext for treatment details), stated as mean values (± SE). All Ranked Sum data were analyzed using two-way, repeated-measures ANOVAs with time and treatment as the indepen-dent variables. Dissimilar letters denote significant differences among treatment groups and time periods (Tukey–Kramer HSD test, p b 0.05). Sample sizes were as follows for un-ripe fish: before; cortisol = 10, control, chase and metyrapone = 9, chase + 1 and sham = 8. After; cortisol = 10, chase and control = 9, chase + 1, sham and metyrapone = 8. Samplesizes were as follows for ripe fish: N = 10 for all groups except for the "after" chase group where N = 9.

Table 2Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) behavior profiles for unripe fish during 4 day trials; values are stated as mean (±SE). All data were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank-Sumtests, and Tukey's HSD test was used to determine where differences lay when a significant effect was obtained (noted by letter scores). All data that are expressed as percentageswere transformed into ArcSine (square root) values before being analyzed. Data for all variables except the aggression score were averaged over days that fish were on establishedterritories. Aggression scores were added for all days spent on territories and divided by number of observational min. Each fish had a similar score for aggressive attacks against,and this score, divided by number of observational min, was subtracted from the previous value to obtain the overall aggression score. Sample sizes were as follows: chase = 9,control and sham = 7, chase + 1 and cortisol = 6, metyrapone = 5.

% Time on territory

Average # of digs

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

Table 3Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) behavior profiles for ripe fish during 4 day trials; values are stated as mean (±SE). All data were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum testsand Tukey's HSD test was used to determine where differences lay when a significant effect was obtained (noted by letter scores). All data that are expressed as percentages weretransformed into ArcSine (square root) values before being analyzed. Data for all variables except the aggression score were averaged over days that fish were on established ter-ritories. Aggression scores were added for all days spent on territories and divided by number of observational min. Each fish had a similar score for aggressive attacks against, andthis score, divided by number of observational min was subtracted from the previous value to obtain the overall aggression score. Sample sizes were as follows: metyrapone = 10,sham, cortisol, control and chase + 1 = 9 and chase = 7.

% Time on territory

Average # of digs

at the Weaver Creek spawning channel, related

between the effects of baseline cortisol and stress-induced cortisol on

mortality to changes in physiological condition and activity levels,

providing a baseline of variables that change as Pacific salmon (spe-

There was evidence that metyrapone treatment caused some egg

cifically sockeye salmon) senesce. To complement that work, the pre-

retention and delayed senescence, as observed in the enclosure

sent study attempted to identify whether stressful conditions can

study (i.e., significantly lower cortisol values compared with other

cause pre-spawn mortality on spawning grounds. It seems plausible

treatment groups in ripe fish). If cortisol spikes immediately prior to

that since cortisol treatment in the present study increased cortisol

ovulation ), this process could have been inhibited

values to those found in senescing fish and at the same time reduced

through the action of metyrapone in blocking cortisol synthesis. Addi-

longevity, then the premature mortality we observed was a function

tionally, cortisol rises again during senescence (),

of this senescence-like physiological state, a state that was not

and this process also could have been inhibited by the action of

reached via the imposition of acute stressors, even though exposure

metyrapone. To examine these possibilities, more detailed time

to acute stressors was expected to acutely elevate circulating cortisol

course of plasma hormone levels is needed. Ideally, metyrapone-

treated fish should be monitored just prior to ovulation, immediatelyfollowing egg release and before morbidity.

Elevated cortisol levels on spawning grounds

Unripe cortisol-treated fish spent less time on their territory than

all other groups. In addition, cortisol-treated fish were significantly

One of the most notable findings of this study was that exposure of

less aggressive than fish in the other treatment groups, and were fre-

pink salmon to acute stressors on spawning grounds did not alter

quently subjected to aggressive attacks from conspecifics. A decrease

spawning ground longevity, reproductive success, or behavior, in ac-

in aggressiveness is detrimental to reproductive success because a fe-

cordance with theory that semelparous animals in general should resist

male benefits from guarding its territory from other females looking

stress (i.e. attenuate stress responses and/or exhibit resistance to the

for suitable habitat, and aggressive behavior is often associated with

effects of elevated stress hormone levels) in favor of allocating energy

reproductive success (). These re-

to their current, and only, reproductive opportunity

sults are supported by previous studies that found that cortisol treat-

). Behavioral and physiological profiles of spawning

ment increased the probability of individual fish (rainbow trout in

Pacific salmon are well documented, but the function of (baseline) cor-

these cases) experiencing increased fin damage indicative of both ag-

tisol elevation in semelparous fish in their natural spawning habitat is

gressive attacks (and becoming socially

not well understood. From a mechanistic standpoint, it has yet to be

subordinate (No behav-

determined how semelparous salmon successfully breed despite circu-

ioral differences were detected among treatments for ripe fish. This

lating cortisol being elevated to a level that would inhibit reproduction

finding suggests that even in the face of chronically elevated cortisol

in other species. However, our data indicate that there is a limit to this

levels, reproductively mature fish maintain key reproductive behav-

capacity because cortisol treatment did impair reproduction.

iors, further supporting the idea that fish with limited reproductive

The scope of the present study does not enable us to speculate

opportunity will still engage in spawning in what would be regarded

about the mechanism of cortisol elevation on spawning grounds. More-

as extreme situations during other life-history phases.

over, we did not measure cortisol receptor occupancy or sensitivity,factors that will affect the ability of (high) cortisol levels to mediate

Metyrapone treatment

target tissue responses, and an issue that ideally would be addressedin future studies. We can conclude, however, that acute elevation of

Metyrapone inhibits the enzyme 11-β hydroxylase, thereby

cortisol levels does not hinder reproductive behaviors and outcome.

preventing synthesis of cortisol from 11-deoxycortisol

In addition, it seems that the second spike in cortisol is an indicator

No significant changes in cortisol titers, reproductive behavior, re-

of impending senescence, as noted in previous studies (e.g.,

productive success, or hormone levels occurred as a result of metyrapone

). If high cortisol levels are evident before spawning is com-

treatment. determined that metyrapone inhibits the

plete, key reproductive behaviors and outcome can be negatively af-

cortisol response to a stressor but does not reduce baseline (non-stressed)

fected, as evidenced in this study by the use of semi-chronic cortisol

cortisol levels. There is also a suggestion that plasma cortisol does not turn

implants. It would have been useful to collect blood immediately fol-

over rapidly for semelparous salmon on spawning grounds

lowing exposure of fish to the acute stressors to assess the extent of

Therefore, it is possible that baseline (i.e. non-

the stress response elicited. In a similar study on stress responsiveness,

stressed) levels of cortisol were maintained, but increases in cortisol levels

observed an increase in cortisol levels from 333 ± 17

with stress were prevented (although this was not tested in the current

to 497 ± 22 ng ml−1 following 2 min of air exposure using Weaver

study). For future studies, responsiveness could be observed following in-

Creek sockeye salmon. Other Pacific salmonids (including sockeye,

jection to determine whether metyrapone-treated fish respond to acute

chum [O. keta], coho [O. kisutch] and Chinook [O. tshawtscha]), as well

stressors. This approach would provide a useful means of distinguishing

as pink salmon, all have been found to experience an acute stress

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

response when exposed to short-term stressors, with cortisol levels re-

covering within 2–4 h (Mike Donaldson, UBC, personal communica-tion). Therefore, the pink salmon in this study likely experienced an

Barry, T.P., Marwah, A., Nunez, S., 2010. Inhibition of cortisol metabolism by 17α,

20β-P: mechanism mediating semelparity in salmon? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.

acute stress response with chasing and air exposure, but were not neg-

165, 53–59.

atively impacted by these acute stressors in terms of reproductive

Barton, B.A., 2002. Stress in fish: a diversity of responses with particular references to

physiology, behavior, or outcome.

changes in circulating corticosteroids. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 517–525.

Barton, B.A., Iwama, G.K., 1991. Physiological changes in fish from stress in aquaculture

with emphasis on the response end effects of corticosteroids. Annu. Rev. Fish Dis. 1,2–26.

Study limitations

Boonstra, R., Hik, D., Singleton, G.R., Tinnikov, A., 1998. The impact of predator-induced

stress on the snowshoe hare cycle. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 371–394.

Bowron, L.K., Munkittrick, K.R., McMaster, M.E., Tetrault, G., Hewitt, L.M., 2009.

Sham-treated fish were negatively affected by the administration

Responses of white sucker (Catostomus commersoni) to 20 years of process and

of a cocoa-butter implant alone. Although longevity was not altered,

water treatment changes at a bleached kraft pulp mill, and to mill shutdown.

sham-treated fish released only 70% of their eggs on average in the

Aquat. Toxicol. 95, 117–132.

Carruth, L.L., Jones, R.E., Norris, D.O., 2002. Cortisol and pacific salmon: a new look at

channel experiment, somewhat less (but not significantly so) than

the role of stress hormones in olfaction home-stream migration. Integr. Comp.

control fish, and released only 15% in the unripe enclosure trials, a

Biol. 42, 574–581.

value significantly lower than that of control fish. When fish were dis-

Cook, K.V., McConnachie, S.H., Gilmour, K.M., Hinch, S.G., Cooke, S.J., 2011. Fitness and

behavioral correlates of pre-stress and stress-induced plasma cortisol titers in pink

sected afterwards, some eggs were observed within the body cavity

salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) upon arrival at spawning grounds. Horm. Behav.

intermingled with the cocoa butter, creating a mass that might not

60, 489–497.

be easily expelled through the vent during spawning. This unexpect-

Cooke, S.J., Hinch, S.G., Crossin, G.T., Patterson, D.A., English, K.K., Shrimpton, J.M., Van

Der Kraak, G., Farrell, A.P., 2006. Physiology of individual late-run Fraser River

ed outcome might be prevented in future studies by using a vehicle

sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) sampled in the ocean correlates with fate

with a lower melting point or by using less volume than used in the

during spawning migration. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 63, 1469–1480.

present study. Indeed, a recent study on brown trout (Salmo trutta)

DeNardo, D.F., Sinervo, B., 1994a. Effects of corticosterone and activity and home range

size of free-ranging male lizards. Horm. Behav. 28, 53–65.

revealed that cocoa butter implants reduced egg and hatchling

DeNardo, D.F., Sinervo, B., 1994b. Effects of steroid hormone interaction on activity and

size () relative to controls, further empha-

home range size of male lizards. Horm. Behav. 28, 273–287.

sizing the need for additional research on improving the mecha-

Dibattista, J.D., Anisman, H., Whitehead, M., Gilmour, K.M., 2005. The effects of cortisol

nisms for experimental delivery of lipophilic hormones, a

administration on social status and brain monoaminergic activity in rainbow trout(Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Exp. Biol. 208, 2707–2718.

technique that is becoming increasingly common in fish physiolo-

Donaldson, E.M., Fagerlund, U.H.M., 1972. Corticosteroid dynamics in Pacific salmon.

gy research (reviewed in ). In our study, be-

Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 3, 254–265.

cause cortisol-treated fish exhibited high cortisol levels with

Doyon, C., Leclair, J., Trudeau, V.L., Moon, T.W., 2006. Corticotropin-releasing factor and

neuropeptide Y mRNA levels are modified by glucocorticoids in rainbow trout,

reduced longevity together with a decrease in the number of eggs

Oncorhynchus mykiss. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 146, 126–135.

released, we believe that our results support a real and significant

Dye, H.M., Sumpter, J.P., Fagerlund, U.H.M., Donaldson, E.M., 1986. Changes in repro-

effect of cortisol itself.

ductive parameters during the spawning migration of pink salmon, Oncorhynchusgorbuscha (Walbaum). J. Fish Biol. 29, 167–176.

Farrell, A.P., Gallaugher, P.E., Routledge, R., 2001a. Rapid recovery of exhausted adult

coho salmon after commercial capture by troll fishing. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 58,

Farrell, A.P., Gallaugher, P.E., Fraser, J., Pike, D., Bowering, P., Hadwin, A.K.M.,

Parkhouse, W., Routledge, R., 2001b. Successful recovery of the physiological status

Because the migratory and spawning processes of Pacific salmon

of coho salmon on board a commercial gillnet vessel by means of a newly designed

are regarded as remarkable challenges, we strive to understand the

revival box. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 58, 1931–1946.

Gamperl, A.K., Vijayan, M.M., Boutilier, R.G., 1994. Experimental control of stress hor-

links among physiology, behavior and fitness in these animals. Salm-

mone levels in fishes: techniques and application. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 4, 215–255.

on migrations historically have shown a large degree of consistency,

Gilmour, K.M., DiBattista, J.D., Thomas, J.B., 2005. Physiological causes and conse-

but any environmental changes or anthropogenic perturbations are

quences of social status in salmonid fish. Integr. Comp. Biol. 45, 263–273.

considered a potential threat to reproduction, and thus survival, of a

Goetz, F.W., 1983. Hormonal control of oocyte final maturation and ovulation in fishes.

In: Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J. (Eds.), Fish Physiology: Reproduction, Behavior and

given population. Our results suggest that acute stressors do not in-

Fertility Control. Academic Press, New York, NY, pp. 117–170. Volume 9 Part 2.

fluence behavior or reproductive outcome when experienced upon

Gregory, T.R., Wood, C.M., 1999. The effects of chronic plasma cortisol elevation on the

arrival at spawning grounds. However, there is a limit to the ability

feeding behavior, growth, competitive ability, and swimming performance ofjuvenile rainbow trout. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 72, 286–295.

of these fish to tolerate elevated cortisol levels because experimental

Heard, W.R., 1991. Life history of pink salmon (Oncohynchus gorbuscha). In: Groot, C.,

cortisol elevation for several days negatively affected reproductive

Margolis, L. (Eds.), Pacific Salmon Life Histories. UBC Press, Vancouver, pp.

success and longevity. Collectively, our results address a void in cur-

Hinch, S.G., Bratty, J.M., 2000. Effects of swim speed and activity pattern on success of

rent research, explaining how varying degrees of cortisol elevation

adult sockeye salmon migration through an area of difficult passage. Trans. Am.

can influence reproductive behavior and spawning success of Pacific

Fish. Soc. 129, 604–612.

salmon. Finally, our study is among the first field studies conducted

Hinch, S.G., Cooke, S.J., Healey, M.C., Farrell, A.P., 2006. Behavioral physiology of fish mi-

grations: salmon as a model approach. In: Farrell, A.P., Brauner, C.J. (Eds.), Behavior

to investigate the ecological consequences of stress during reproduc-

and Physiology of Fish: Fish physiology, 24.

tion for a semelparous species.

Hoogenboom, M.O., Armstrong, J.D., Miles, S., Burton, T., Groothuis, T.G.G., Metcalfe,

N.B., 2011. Implantation of coca butter reduces egg and hatchling size in Salmotrutta. J. Fish Biol. 79, 587–596.

Hopkins, T.E., Wood, C.M., Walsh, P.J., 1995. Interactions of cortisol and nitrogen

metabolism in the ureogenic toadfish Opsanus beta. J. Exp. Biol. 198, 2229–2235.

Hruska, K.A., Hinch, S.G., Healey, M.C., Farrell, A.P., 2007. Electromyogram telemetry,

This research was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering

non-destructive physiological biopsy, and genetic markers: linking recent tech-niques with behavioral observations for the study of reproductive successes in

Research Council of Canada Discovery and Strategic grants to S.J.C.,

sockeye salmon mating systems. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 54, 17–29.

S.G.H., A.P.F. and K.M.G. Research was also supported by the Depart-

Hruska, K.A., Hinch, S.G., Healey, M.C., Patterson, D.A., Larsson, S., Farrell, A.P., 2010. In-

ment of Fisheries and Oceans (Canada) Environmental Watch Program

fluences of sex and activity level on physiological changes in individual adultsockeye salmon during rapid senescence. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 83, 663–676.

led by D.A.P. Field support was provided by Connie O'Connor, Alison

Janz, D.M., McMaster, M.E., Munkittrick, K.R., Van Der Kraak, G., 1997. Elevated ovarian

Colotelo, Mike Donaldson, Graham Raby, Charlotte Whitney, Kim

follicular apoptosis and heat shock protein-70 expression in white sucker exposed

Hruska, Juliette Mudra and Tim Clark. Jayme Hills and Vanessa Ives

to bleached kraft pulp mill effluent. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 147, 391–398.

Jardine, J.J., Van Der Kraak, G.J., Munkittrick, K.R., 1996. Capture and confinement stress

conducted plasma analyses. Rick Stitt and the Weaver Creek Spawning

in white sucker exposed to kraft pulp mill effluent. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 33,

Channel staff provided logistical and technical support.

S.H. McConnachie et al. / Hormones and Behavior 62 (2012) 67–76

Mathes, M.T., Hinch, S.G., Cooke, S.J., Crossin, G.T., Patterson, D.A., Lotto, A.G., Farrell,

Rodela, T.M., McDonald, M.D., Walsh, P.J., Gilmour, K.M., 2009. The regulatory role of

A.P., 2010. Effect of water temperature, timing, physiological condition, and lake

glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in pulsatile urea excretion of the

thermal refugia on migrating adult Weaver Creek sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus

gulf toadfish, Opsanus beta. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1849–1858.

nerka). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 67, 70–84.

Schreck, C.B., 2010. Stress and fish reproduction: the roles of allostasis and hormesis.

McBride, J.R., Fagerlund, U.H.M., Dye, H.M., Bagshaw, J., 1986. Changes in structure of

Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 165, 549–556.

tissues and in plasma cortisol during the spawning migration of pick salmon,

Schreck, C.B., Contreras-Sanchez, W., Fitzpatrick, M.S., 2001. Effects of stress on fish re-

Oncorhynchus gorbuscha (Walbaum). J. Fish Biol. 29, 153–166.

production, gamete quality, and progeny. Aquacult. 197, 3–24.

Mehranvar, L., Healey, M., Farrell, A., Hinch, S., 2004. Social versus genetic measures of

Silverin, B., 1997. The stress response and autumn dispersal behavior in willow tits.

reproductive success in sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka. Evol. Ecol. Res 6,

Anim. Behav. 10, 451–459.

Stein-Behrens, B.A., Sapolsky, R.M., 1992. Stress, glucocorticoids, and aging. Aging Clin.

Milla, S., Wang, N., Mandiki, S.N.M., Kestemont, P., 2009. Corticosteroids: friends or foes

Exp. Res. 4, 197–210.

of teleost fish reproduction? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 153,

Tierney, K.B., Patterson, D.A., Kennedy, C.J., 2009. The influence of maternal condition

on offspring performance in sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka. J. Fish Biol. 75,

Milligan, C.L., 2003. A regulatory role for cortisol in muscle glycogen metabolism in

rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 3167–3173.

Van Der Kraak, G., Munkittrick, K.R., McMaster, M.E., MacLatchy, D.L., 1998. A compar-

Mishra, A., Joy, K.P., 2006. Effects of gonadotropin in vivo and 2-hydroxyoestradiol-17

ison of bleached kraft mill effluent 17 beta-estradiol, and beta-sitisterol effects on

beta in vitro on follicular steroid hormone profile associated with oocyte maturation

reproductive function in fish. In: Kendall, R.J., Dickerson, D.L., Giesy, J.P., Suk, W.P.

in the catfish Heteropneustes fossilis. J. Endocrinol. 189, 341–353.

(Eds.), Principles and Processes for Evaluation Endocrine Disruption in Wildlife.

Mommsen, T.P., Vijayan, M.M., Moon, T.W., 1999. Cortisol in teleosts: dynamics, mech-

SETAC Press, Florida, pp. 249–265.

anisms of action, and metabolic regulation. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 9, 211–268.

Wagner, G.N., Hinch, S.G., Kuchel, L.J., Lotto, A., Jones, S.R.M., Patterson, D.A., Macdonald,

Morbey, Y.E., Brassil, C.E., Hendry, A.P., 2005. Rapid senescence in Pacific salmon. Am.

J.S., Van Der Kraak, G., Shrimpton, M., English, K.K., Larsson, S., Cooke, S.J., Healey,

Nat. 166, 556–568.

M.C., Farrell, A.P., 2005. Metabolic rates and swimming performance of adult Fraser

Negro-Vilar, A., 1993. Stress and other environmental factors affecting fertility in men

River sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) after a controlled infection with

and women: overview. Environ. Health Perspect. 101, 59–64.

Parvicapsula minibicornis. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 62, 2124–2133.

Pickering, A.D., Pottinger, T.G., Carragher, J., Sumpter, J.P., 1987. The effects of acute and

Wingfield, J.C., 1988. Changes in reproductive function of free-living birds in direct

chronic stress on the levels of reproductive hormones in the plasma of the mature

response to environmental perturbations. In: Stetson, M.H. (Ed.), Processing of Envi-

brown trout, Salmo trutta L. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 68, 249–259.

ronmental Information in Vertebrates. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 121–148.

Quinn, T.P., Foote, C.J., 1994. The effects of body size and sexual dimorphism on the repro-

Wingfield, J.C., 2003. Control of behavioral strategies for capricious environments.

ductive behavior of sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka. Anim. Behav. 48, 751–761.

Anim. Behav. 66, 807–816.

Quinn, T.P., Unwin, M.J., Kinnison, M.T., 2000. Evolution of temporal isolation in the

Wingfield, J.C., Sapolsky, R.M., 2003. Reproduction and resistance to stress: when and

wild: genetic divergence in timing of migration and breeding by introduced

how. J. Neuroendocrinol. 15, 711–724.

Chinook salmon populations. Evolution 54, 1372–1385.

Wingfield, J.C., Maney, D.L., Breuner, C.W., Jacobs, J.D., Lynn, S., Ramenofsky, M.,

Rand, P.S., Hinch, S.G., Morrison, J., Foreman, M.G.G., MacNutt, M.J., Macdonald, J.S.,

Richardson, R.D., 1998. Ecological bases of hormone–behavior interaction: the

Healey, M.C., Farrell, A.P., Higgs, D.A., 2006. Effects of river discharge, temperature,

emergency life history stage. Am. Zool. 38, 191–206.

and future climates on energetic and mortality of adult migrating Fraser River

Young, J.L., Hinch, S.G., Cooke, S.J., Crossin, G.T., Patterson, D.A., Farrell, A.P., Van Der

sockeye salmon. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 135, 655–667.

Krakk, G., Lotto, A.G., Lister, A., Healey, M.C., English, K.K., 2006. Physiological and

Robertson, O.H., Wexler, B.C., 1959. Hyperplasia of the adrenal cortical tissue in Pacific

energetic correlates of en route mortality for abnormally early migrating adult

salmon (genus Oncorhynchus) and rainbow trout (Salmo gairnerii) accompanying

socleye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) in the Thompson River, British Columba.

sexual maturation and spawning. Endocrinology 65, 225–238.

Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 63, 1067–1077.

Source: http://www.fecpl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/HB-McConnachie-et-al-2012.pdf

Personalised, Serendipitous and Diverse Linked Data Resource Recommendations Milan Dojchinovski and Tomas Vitvar Web Intelligence Research Group Faculty of Information Technology Czech Technical University in Prague Abstract. Due to the huge and diverse amount of information, the ac-tual access to a piece of information in the Linked Open Data (LOD)cloud still demands significant amount of effort. To overcome this prob-lem, number of Linked Data based recommender systems have been de-veloped. However, they have been primarily developed for a particulardomain, they require human intervention in the dataset pre-processingstep, and they can be hardly adopted to new datasets. In this paper, wepresent our method for personalised access to Linked Data, in particularfocusing on its applicability and its salient features.

Allergology International. 2007;56:37-43DOI: 10.2332! Awarded Article, Annual Meeting of JSA The Relationship between ExhaledNitric Oxide Measured with an Off-lineMethod and Airway ReversibleObstruction in Japanese Adults withAsthmaTakahiro Tsuburai1, Naomi Tsurikisawa1, Masami Taniguchi1, Sonoko Morita1, Emiko Ono1,Chiyako Oshikata1, Mamoru Ohtomo1, Yuji Maeda1, Kunihiko Ikehara2 and Kazuo Akiyama1