Mmcinfo.co.za

male circumcision for Hiv prevention

WHO TecHnical advisOry GrOup On

innOvaTiOns in Male circuMcisiOn:

evaluation of

two adult devices

male circumcision for Hiv prevention

WHO TecHnical advisOry GrOup On

innOvaTiOns in Male circuMcisiOn:

evaluation of

two adult devices

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Male circumcision for HIV prevention : WHO Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision : evaluation of two adult devices, January 2013 : meeting report.

1.HIV infections - prevention and control. 2.Circumcision, male – therapeutic use. 3.Circumcision, male –

instrumentation. 4.Circumcision, male – methods. 5.Surgical instruments – adverse effects. 6.Risk factors.

7.Program development. 8.Guideline. 9.Adult. I.World Health Organization.

ISBN 978 92 4 150563 5

(NLM classification: WC 503.4)

World Health Organization 2013

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int)

or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]).

Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html).

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of

any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or

recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in

this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use.

Layout by Genève Design

Printed by the WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland

list of participants

Members

Professor Kasonde Bowa

Mr Edgar Makona

Associate Professor of Urology UNZA & CBU SOM Honorary

National Focal Point

Consultant Urologist UTH

Global Youth Coalition on HIV/AIDS

Inaugural Dean CBU School of Medicine

P.O. Box 14907, 00800, Nairobi

Head MC Unit University Teaching Hospital

UNZA School of MedicineP.O. Box 50110, Lusaka, Zambia

Dr Timothy Hallett

Ms Emily Miesse-Gumkowski

Development Engineer

Imperial College London

North Haven, CT 06473, USA

South Kensington Campus, London SW7 2AZUnited Kingdom

Dr Timothy Hargreave

Dr Pius Musau

Urological Surgeon

20 Cumin Place Edinburgh EH9 2JX

Department of Surgery

Moi University, School of MedicineNandi Road - P.O. Box 5455, 30100Eldoret, Kenya

Dr Theobald Hategekimana

Dr William Potter

Stapleford Scientific Services

University Teaching Hospital (CHU)

P.O. Box 254, Kigali, Rwanda

Professor John Krieger

Dr Christopher Samkange

Department of Urology

University of Washington

Institute of Continuing Health Education

1959 N.E. Pacific

University of Zimbabwe

Seattle, WA 98195, USA

College of Health Sciences, Harare, Zimbabwe

Dr Ira Sharlip

Dr Helen Weiss

Urological Surgeon

Chair, American Urological Association Task Force

Head of IDE and Reader in Epidemiology and

on Male Circumcision

International Health

San Francisco, CA, USA

London School of Hygiene and Tropical MedicineKeppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, United Kingdom

Dr Stephen Watya

Uro Care

P.O. Box 25974

Kampala, Uganda

Observers

Ms Melanie Bacon

Dr Emmanuel Njeuhmeli

Scientific Program Manager

Senior Biomedical Prevention Advisor

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Global Health Bureau/Office of HIV/AIDS

9000 Rockville Pike

Technical Leadership & Research Division

Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA

1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, MW, Washington D.C, USA

Dr Naomi Bock

Dr Jason Reed

HIV Prevention Branch, Division of Global

Senior Technical Advisor

HIV/AIDS, Centers for Global Health

Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

2100 Pennsylvania Ave, Suite 200

1600 Clifton Rd. Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Washington DC 20037, USA

Ms Agnes Chidanyika

Dr Renee Ridzon

Technical Specialist

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

Consultant to BMGF

P.O. Box 2530, DK - 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Ms Celeste Sandoval

Science Advisor

UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland

WHO Secretariat

Dr Rachel Baggaley

Ms Julia Samuelson

Acting Coordinator

Male Circumcision Focal Point

Key Populations and Innovative Prevention

Key Populations and Innovative Prevention

Department of HIV/AIDS

Department of HIV/AIDS

Dr Gaby Vercauteren

Ms Irena Prat

Department of Essential Medicines and

Department of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical

Pharmaceutical Policies

Dr Buhle Ncube

Dr Emil Asamoah-Odei

Male Circumcision Focal Point

Programme Manager

HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infections

Regional Office for Africa (AFRO)

Dr Nuhu O Yaqub

Maternal, Newborn, Child Adolescent Health

Consultants

Ms Nita Bellare

Dr Doris Mugrditchian

Key Populations and Innovative Prevention

Key Populations and Innovative Prevention

Department of HIV/AIDS

Department of HIV/AIDS

Dr Timothy Farley

Dr Nicolas Magrini

Head, Drug Evaluation Unit

Nyon, Switzerland

WHO Collaborating Centre in Evidence-Based Research Synthesis and Guideline DevelopmentEmilia Romagna Health and Social Care Agency Viale Aldo Moro, 21, 40127 Bologna, Italy

acknowledgments

WHO would like to thank all the participants of the WHO

could be held in a timely manner. The principal writers of this

Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision, in

report were Tim Farley, Doris Mugrditchian and Julia Samuelson.

particular, the co-chairs, Timothy Hargreave and Stephen Watya.

We also express our thanks for funding support from the Bill and

WHO would also like to acknowledge all the researchers who

Melinda Gates Foundation and the US President's Emergency

have shared data, published or confidential, so that this meeting

Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

Department of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies

failure modes and effects analysis

Global Harmonization Task Force

human immunodeficiency virus

Instructions for Use

International Organization for Standardization

US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

prequalification

serious adverse event

Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

Visual analogue score

Voluntary medical male circumcision

World Health Organization

executive summary

The World Health Organization (WHO) Technical Advisory

in about one year as more experience with use of the device

Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision (TAG) met at

accumulates in diverse programmatic settings outside the context

WHO headquarters in Geneva in January 2013. The focus of

the meeting was a review of the clinical performance of two specific male circumcision devices (PrePex and ShangRing) as

The PrePex (elastic collar compression) device had been

part of the product review in the WHO Prequalification of Male

evaluated in eight studies conducted in Rwanda, Uganda and

Circumcision Devices Programme. This review was based on

Zimbabwe involving about 2400 device placements. The range

clinical data collected in the context of the Framework for clinical

and scope of these studies met the criteria established in the

evaluation of male circumcision devices (WHO), which stipulates

WHO Framework for clinical evaluation of devices for male

a progressive series of clinical studies to establish the efficacy,

circumcision. About 7% of clients could not have the PrePex

safety, acceptability and clinical performance of the device when

device placed for various anatomical and technical reasons but

used by trained mid-level providers. The evaluation was also

would have been eligible for conventional surgical circumcision.

informed by the failure modes and effects analysis conducted

Circumcision was successfully completed using the PrePex in

by WHO for the collar clamp and elastic collar compression

99.5 % of clients on whom the device was successfully placed.

type devices. The meeting discussions also provided inputs on

Adverse events occurred in 1.7% of clients, the majority of

programmatic considerations for guidance under development on

which were mild or moderate. Serious adverse events occurred

the use of devices, information gaps and research needs.

in 0.4% of clients, some of whom required prompt intervention to prevent potentially serious long-term sequelae. Over half

The ShangRing (collar clamp) device had been evaluated in five

of these serious events were due to device displacement or to

studies in Kenya, Uganda and Zambia, involving almost 2000

device removal (including self-removal) secondary to pain or

device placements. These clinical studies met the minimum

discomfort. These cases resulted in pain, swelling and occasional

requirements necessary before a device can be considered for

blistering of the partially necrosed foreskin tissue, requiring

prequalification. The overall estimated proportion of clients not

urgent intervention by a skilled surgeon to prevent severe local or

eligible for male circumcision with the ShangRing device was

systemic infection and/or permanent disfigurement of the penis.

about 1%. In about one of every 200 clients, it was not possible

In the studies conducted to date, appropriate surgical facilities

to complete the circumcision procedure with the device alone.

have been available, and all cases were successfully managed

Some men required immediate conversion to conventional

with no long-term sequelae. Client instructions must clearly

surgical circumcision to avoid any serious complications. The

describe safe use of the device, symptoms that may develop with

conventional surgery was performed by a person experienced

device displacement or early removal, as well as the possible

in standard surgical circumcision who was available on site,

serious outcomes and surgical interventions that may be needed

together with appropriate instruments and supplies. The data

if instructions on abstinence and wound care are not followed.

demonstrated that the ShangRing was efficacious and safe

Similarly, PrePex providers must be appropriately trained to

when used by suitably trained and equipped providers, with a

recognize the rare serious complications that can occur if the

circumcision success rate of over 99%. No serious adverse events

device is displaced and must ensure that such clients are rapidly

occurred in 1983 successful device placements. A total of 20 men

provided appropriate management.

(1.0%) experienced moderate adverse events. All adverse events were managed with, at most, minor intervention and resolved,

On the basis of the clinical evaluation, the TAG concluded that

leaving no long-term sequelae. The adverse event rates were

the requirements for clinical studies necessary before a device is

similar to those observed with conventional surgical circumcision. considered for WHO prequalification had been satisfactorily met.

The TAG considered the device to be clinically efficacious in male

The TAG considered the ShangRing to be clinically efficacious

circumcision and safe for use among healthy men 18 years and

and safe for use in healthy men age 18 years and older, when

older when used by trained mid-level providers in public health

performed by trained providers in public health programmes.

programmes, provided that surgical backup facilities and skills

Skills and surgical facilities should always be available to safely

are available within 6–12 hours to manage events that could

convert technical failures of device placement to a conventional

lead to serious complications. The TAG based its conclusion on

procedure. The TAG based its conclusion on the data currently

the data currently available. This conclusion must be reassessed

available and recognized that this is only one component of the

in about one year as more experience and data accumulate with

prequalification assessments. This conclusion must be reassessed

use of the device in diverse programmatic settings outside the context of studies.

introduction

The HIV Department at the WHO headquarters convened

male circumcision (1), published in 2012, describes the clinical

a meeting of the WHO Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on

evaluation pathways required to provide sufficient evidence of

Innovations in Male Circumcision in Geneva, Switzerland, 29–31

efficacy and safety of a new male circumcision device. These

January 2013. The purpose of the meeting was to provide

programmatic and technical updates and to evaluate and advise on the clinical efficacy and safety of two devices for adolescent

• initial studies to establish safety and acceptability;

and adult male circumcision that have formally entered the

• at least two independent randomized control ed trials comparing

WHO prequalification process. The three-day meeting brought

the device against an established method of circumcision

together members and observers of the TAG along with the WHO

performed by providers skil ed to offer either method of male

Secretariat and staff from the HIV Department, the Department

circumcision in settings of intended final use; and

of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies, the WHO

• at least two field studies of procedures involving relevant

Regional Office for Africa, and the Intercountry Support Team.

populations, types of facilities and performed by suitably

trained and qualified mid-level or non-physician providers in settings of intended final use.

In March 2007, responding to compelling evidence from three

The information generated from these studies forms the basis for

randomized controlled clinical trials confirming the results from

WHO to assess and provide advice on the use of a device in adult

ecological studies, WHO and the Joint United Nations Programme

and adolescent VMMC programmes for HIV prevention in high

on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) issued recommendations that medical

HIV prevalence, resource-limited settings.

male circumcision be considered as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package in countries with generalized epidemics.

WHO also established the Prequalification (PQ) of Male

Since then, 14 countries in east and southern Africa have

Circumcision Devices Programme for HIV Prevention in the

taken action towards the scale-up of voluntary medical male

Department of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies

circumcision (VMMC) for HIV prevention.

(EMP). The TAG reviews the clinical data on a specific product and advises the Department of EMP whether the evidence

Modelling studies indicate that national male circumcision

demonstrates that a specific device is efficacious in removal of

programmes will have the greatest public health impact in these

the foreskin and safe for use in the intended population. The

14 priority countries, averting up to 3.4 million HIV infections

Department of EMP assesses the product to see that it meets

through 2025, and will provide the largest cost-saving (USD

international standards (through a review of the product dossier)

16.5 billion) if services are scaled up rapidly. However, currently

and inspects the manufacturing site(s) to assess the adequacy

recommended surgical methods for adult male circumcision

and effectiveness of the manufacturer's quality management

involve considerable time and skill. Thus, innovations in the

system and the correct implementation of their documented

procedure, including male circumcision devices, have been under

study over the past few years.

By the end of 2012, three manufacturers had entered the PQ

In 2008 and 2009 initial consultations reviewed the landscape of

Programme; sufficient data was judged to be available on two

technologies for male circumcision. In 2010 the WHO established

devices—the ShangRing and PrePex. The TAG was, therefore,

a Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision

convened in January 2013 to review all available data on these

(henceforth "the TAG") for the purpose of reviewing and

devices, to advise on the clinical evaluation component of PQ and

advising the WHO on innovations in male circumcision, including

highlight programmatic considerations in the use of each device

devices. The Framework for the clinical evaluation of devices for

and to advise on priority research needs.

declaration of interests

The objectives of the meeting were to:

At the beginning of the meeting, the WHO secretariat explained the reasons for the written and verbal declarations of interests

• update the TAG on the:

and summarized the pertinent interests that had been declared

– status of devices in the WHO PQ of Male Circumcision

in writing prior to the meeting. All participants were invited to

Devices Programme

declare verbally to the group any other conflicts, or potential

– device risk assessments and

conflicts, of interest. No other members stated any current or potential conflicts of interest that might affect their impartiality,

– development of guidance on use of devices and issues from

judgment or advice. Review of the declarations by the secretariat

the research that will inform the guidance.

and the TAG chairs identified no significant conflicts or potential

• review all available clinical research findings on two male

conflicts of interest that would disqualify or restrict participation.

circumcision devices for adolescents and adults, specifically the PrePex and the ShangRing, to inform prequalification

The primary types of potential conflicts were due to participants'

involvement on research teams that had or were currently

• advise the WHO on:

studying one or more devices, involvement in modelling studies and a declared advocacy of "cautious optimism in favour" of

– review of study requirements for clinical evaluation of

devices. One participant had been previously employed by a

devices of the same category;

company that worked on the development of male circumcision

– operational and programmatic considerations on use of

devices, two currently or previously worked on male circumcision

devices to be addressed in the guidance;

device technologies, and one worked with and currently consults

– additional technical innovations that WHO should assess,

for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has supported

or should stimulate further development of, to improve

device development and research.

coverage and/or accelerate scale-up of male circumcision in priority countries; and

– priority research to further advance work on male

circumcision for HIV prevention.

meeting process and roles of participants

The TAG is comprised of international y recognized experts

including representatives of research institutes, clinical scientists,

statisticians, medical device regulators and programme managers

in the field. The TAG is composed of members and observers.

Members of the TAG are experts appointed because of their

expertise in the field and are involved in the formulation of

recommendations. Observers from col aborating partners with

an interest in expanding male circumcision programmes for HIV

prevention represent the perspective of their institutions as wel

as contribute their technical knowledge. Observers do not directly

participate in formulating the advice and recommendations

of the TAG. Given the nature of the meeting documents that

were reviewed, TAG participants agreed to strict standards of

confidentiality and submitted signed confidentiality agreements.

programme and tecHnical updates

wHo Hiv department progress during 2012 WHO also convened a small expert group to conduct a risk

and planned guidance

analysis of devices in mid-2012. The outputs of this exercise (see below) helped to identify key potential risks associated with use of devices. WHO is preparing guidance on the use of devices for

The WHO Secretariat provided programmatic updates on the

adolescent and adult VMMC for HIV prevention in accordance

work of the WHO HIV Department during 2012. WHO remains

with the WHO guideline review processes.

fully committed to identifying and assessing priority technical innovations in male circumcision, including devices that have

The conclusions of this TAG meeting will inform several guidance

the potential to:

products on devices and device use, in particular:

• make the male circumcision procedure safer, easier and quicker

• The WHO PQ Programme component on clinical safety and

than current methods;

efficacy of the ShangRing and PrePex devices. This is one

• facilitate more rapid healing and/or entail less risk of HIV

part of the full product review and contributes to the decision

transmission or acquisition in the immediate post-operative

whether or not to prequalify a particular device. A summary

report will be provided on the clinical evaluation of each specific device.

• be used safely by (mid-level) health-care providers with a

shorter period of training than required for conventional

• Programmatic and operational considerations in the WHO

surgical male circumcision; and

guidance on use of devices for adolescent and adult VMMC for HIV prevention.

• be more cost-effective for male circumcision scale-up than

standard surgical methods.

The WHO also sought inputs from the TAG on additional technical considerations, including a review of the clinical

Given that a number of devices were available on the market, the

evaluation requirements to demonstrate equivalent efficacy and

WHO, with the inputs of the TAG, had produced the following

safety of a similar product, further research to be catalysed, and

guidance products to inform evaluation and use of devices:

additional promising technologies that should be considered.

• Framework for clinical evaluation of devices for male

circumcision (1), which:

prequalification of male circumcision

– outlines the clinical pathway for assessing suitability of

a device, including the minimum requirement for WHO consideration of efficacy and safety (two comparative

The WHO PQ of Male Circumcision Devices Programme

studies in different settings and two field studies in settings

undertakes a comprehensive assessment of the applications

of intended use);

submitted by device manufacturers through a standardized procedure based on international best practices and WHO PQ

– lists ideal device characteristics and potential evaluation

requirements, which include three main components:

– provides suggestions for the stepwise introduction of a new

• Review of the application form with summary information

device, with scale-up in mind; and

about the product

– highlights regulatory considerations and the WHO

• Review of the product dossier, including review of clinical

• Use of devices for adult male circumcision in public health HIV

• Inspection of the manufacturing site(s).

prevention programmes: conclusions of the WHO Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision (2), which

The role of the TAG in the PQ of Male Circumcision Devices

provided initial conclusions based on limited evidence on the

Programme process is review of the clinical safety and efficacy

use of the PrePex device in early 2012.

of the device based on clinical evidence generated within the clinical evaluation framework described earlier.

– As the data reviewed were from a series of three clinical

studies conducted in only one low-resource country

To date, three devices—namely the PrePex, ShangRing and

(Rwanda), the TAG concluded that additional studies were

AlisKlamp—have entered the WHO PQ Programme. The

needed before advice could be generalized beyond Rwanda.

manufacturer of a fourth device, the TaraKlamp, has expressed

During 2012 the WHO PQ of Male Circumcision Devices

interest but has not yet submitted an application. Review of the

Programme reviewed two device products and responded

PrePex device has moved the most swiftly through the stages

to requests from manufacturers of two other devices. More

of PQ and is the closest to meeting clinical evaluation and other

details on PQ are noted below. The link to the PQ documents

requirements. Once a product has been prequalified, it will be

included on a list of devices published on the WHO web site (see

above). This paves the way for procurement by UN agencies,

WHO Member States, donors and other interested purchasers.

or process) of the device to the PQ Programme. It is not the

Prequalification does not imply WHO approval to import or to use

manufacturer but rather the WHO programme that decides what

the device in any particular country, as this the prerogative and

constitutes a "significant" change in the design of the product or

responsibility of the national regulatory authorities.

the manufacturing process, and if a re-evaluation is needed.

The main points from discussions that followed these updates included:

technical update 1: risk analysis of male

• The steps in the PQ process require significant staff time and

financial resource investments.

The WHO held a technical consultation in Geneva, 6–7 August

– These financial resources have been provided by donors and

2012, to reach consensus on the classification scheme for male

the public sector, and the manufacturer is not charged by

circumcision devices and to conduct a risk analysis on of devices.

WHO for work performed for PQ of a product.

Three categories of in-situ devices (i.e. devices that remain in

– The process can take many months before the manufacturer

place for some period of time) for adolescent and adult male

satisfactorily meets requirements. It involves the

circumcision were agreed upon based on their mechanism of

manufacturer submitting complete documentation,

responding to requests for clarification, and implementing suggested corrective actions following WHO site inspections.

• Clamp, with subcategories: a) collar clamp (e.g. ShangRing); b)

• A PQ decision is time-limited. WHO will arrange for the

vice clamp (e.g. TaraKlamp)

products and manufacturing sites included in the WHO list

The mechanism of action consists of rapid, tight compression

of prequalified male circumcision devices to be reassessed

between hard surfaces to achieve haemostasis. Compression

at regular intervals. Prequalified diagnostic products are

is sufficient to prevent slippage of tissue such that the foreskin

reassessed usually every three to five years, or sooner if

can be removed at the time of, or soon after, application of

warranted, such as in the case of reports of product defects. If,

the device. Part or all of device is left in situ for more than 24

as a result of reassessment, it is found that a product and/or

hours. Injection with local anaesthesia is required.

specified manufacturing site no longer complies with the WHO

• Ligature compression (e.g. Plastibell for infants)

requirements, such products and manufacturing sites will be

The mechanism of action consists of a rapid, tight compression

removed from the list. Failure of a manufacturer to participate

between a hard surface and a non-rigid ligature that is tied to

in the reassessment procedure also will lead to removal from

hold the foreskin in place between the hard surface and the

the list. For prequalified devices the same principle will be

ligature. Compression is sufficient to achieve haemostasis and

applied, with re-inspection occurring sooner as indicated,

prevent slippage of tissue such that the foreskin can be removed

including for a new product and manufacturer.

at the time of, or soon after, application of the device. Part or

• A PQ decision can be retracted if concerns with safety are

all of the device is left in situ for more than 24 hours. Local

substantiated. Once a product is prequalified, International

anaesthesia is required. The compression force and the security of

Organization for Standardization (ISO) 13485 requires

the knot depend on the provider.

the reporting of serious adverse events and post-market

• Elastic collar compression (e.g. PrePex).

surveillance. Since national adverse event monitoring systems

The mechanism of action consists of slow compression

are often weak, the TAG urged the standardization of post-

between an elastic ring and a hard surface that is sufficient to

market surveillance and that countries improve the reporting of

occlude circulation and produce tissue ischaemia. Part or all

adverse events. PEPFAR will collaborate with WHO to support

of the device and the foreskin are left in place for more than

national programmes in post-market surveillance of the use of

24 hours, thereby causing ischaemic necrosis of the foreskin.

male circumcision devices.

The device and the foreskin are removed at a later date. Such

• The manufacturer must report, in addition to serious adverse

devices can be applied without the need for injected local

events, change(s) in the design or manufacturing (material

The consultation then used the Failure Modes and Effects Analysis

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the results of the risk analysis of two

procedure (FMEA) which is one of the techniques specified in

male circumcision device categories.

ISO 14971, the international standard for the application of risk management to medical devices, to systematical y analyze,

Some key points for programme introduction were noted. As

evaluate and propose control measures on use of devices.

devices are rolled out from study to field conditions and with

According to ISO 14971, the manufacturer is responsible for

broader use, more failures and failure modes can be expected

establishing, documenting and maintaining a continuous process

to occur. When the device is procured and used in a programme

of risk management/quality feedback for the lifetime of a device,

supported by a government or donor, it is more likely that

including identifying hazards associated with a medical device,

safety will be monitored through standardized serious adverse

estimating and evaluating the associated risks, control ing these

event (SAE) reporting than when it is procured and used by the

risks and monitoring the effectiveness of these controls. Feedback

private sector. User instructions are critical. Clinicians will need

information is obtained from the market in the form of customer

to be educated not to use devices that have not been clinically

complaints and proactive post-market surveil ance as well as

evaluated and are not prequalified. Devices that fail should be

internal y from production processes, if a problem is encountered

sent back to the manufacturer for analysis.

before the product or lot reaches the market.

The WHO consultation applied the FMEA technique to a device

technical update 2: clinical evaluation of

category: identifying failure modes associated with the specific

the prepex and the shangring devices

device category, quantifying the risk and identifying actions to mitigate risks. The exercise focused on device categories for use

The TAG conducted a detailed review of all available clinical

in adolescents and adults (rather than infants) and on those that

safety, efficacy and acceptability data on two male circumcision

had entered the WHO PQ Programme. The FMEA technique takes

devices for adolescents and adults, the ShangRing and the

into account three factors:

PrePex. Data on the safety and efficacy of the PrePex were available from eight studies conducted in three countries in

• potential severity of an outcome (consequence of the harm)

east and southern Africa (Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe).

• frequency of occurrence (per client procedure) and

These studies included an initial safety and efficacy study, two

• detectability of any potential failure (ease with which the

randomized comparative trials, two completed field studies and

failure can be detected at time of deployment or while the

interim analyses from two ongoing field studies. Safety and

device is in situ).

efficacy data for the ShangRing included data from five studies conducted in three countries (Kenya, Zambia and Uganda). Data

Individual scores were assigned to each potential failure mode

from studies conducted in China were summarized (3–6), but

for each of the three factors, using a scale of 1 to 5. A total

the TAG decided these data were not directly relevant to the

risk score was calculated by multiplying the individual factor

population where the intervention is prioritized. In addition, it

scores (highest score possible risk score is 125). A risk score of

was not clear whether the version of the device used in these

25 or above was considered by the participants as a priority,

studies was the same as that used in the African studies.

warranting that actions to mitigate risk be identified. Such actions could be through:

• Provider instructions, warnings and contraindications on use• Client information on use• Specification of the device (in its design and/or the material(s)

• Process and quality controls in manufacturing

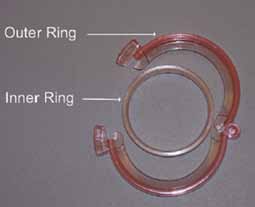

1. shangringThe ShangRing is produced by Wuhu Snnda Medical Treatment

Figure 1: The original design of the ShangRing is

Appliance Technology Co. Ltd, Wuhu City, China. It is a

shown at the top (7). The design used in the

minimal y invasive method for boys and adult men undergoing

African studies is shown at the bottom (8).

circumcision for phimosis or electively and was first described in the international literature in 2008 (7). The ShangRing is a col ar clamp circumcision type of device. The device consists of two concentric plastic rings that sandwich the foreskin of the penis. The mechanism of action consists of a rapid, tight compression of the foreskin between the hard surfaces to achieve haemostasis. The compression is sufficient to prevent slippage of tissue such that the foreskin can be removed at the time of device application. The device must be sterile. Anaesthetic injection is required.

The device is applied by placing the inner ring over the shaft of the penis at the height of the coronal sulcus. The foreskin is everted over the inner ring and then clamped in place and crushed by the outer ring. The foreskin distal to the device is then cut away. The device is removed at seven days by releasing the clamped outer ring, gently separating the inner ring from the healing wound, and then cutting the ring in two places to remove it from the shaft of the penis.

The original device used in China is shown on the top in Figure 1. It was available in different diameters, ranging from 13 mm to 40 mm in 2 or 3 mm increments. The device used in all the African studies is depicted at the bottom in Figure 1. It differed from the original design only with regard to the mechanism to secure the outer ring—the threaded locking mechanism in the original design was replaced with a ratchet that facilitated positioning and adjustment of the device over the everted foreskin. Also, the device was available in 26 mm to 40 mm diameter sizes in 1 mm increments. The correct device size is selected based on measurement of the penile circumference at the level of the coronal sulcus with a specially marked tape.

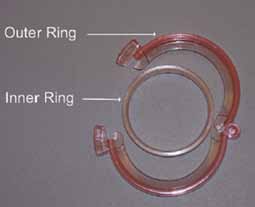

2. prepexTMThe PrePexTM is produced by Circ MedTech Limited in Israel.

Figure 2: The PrePex device

The device was specifically designed to be used by mid-level providers in resource-limited settings and to avoid the need for local anaesthesia during device placement. The device is an elastic collar compression type of device. It consists of an inner ring placed under the foreskin at the level of the coronal sulcus and an elastic O-ring that is aligned and released over the groove of the inner ring using an applicator (Figure 2). Blood flow to the foreskin is restricted by compression of the elastic ring on the inner ring, resulting in ischemia and necrosis of the foreskin. The device and necrotic residual foreskin are removed at seven days. Since there is neither cutting nor crushing of live tissue that would result in intense pain, there is no need for injectable local anaesthesia. The absence of bleeding means that there is no need for suturing and the device does not have to be sterile at the time of use.

process of evaluation of study data on

• Successful circumcision was defined as removal of sufficient

foreskin such that the coronal sulcus was visible with the penis in a flaccid (non-erect) state. Circumcision failures included clients who needed an additional intervention to complete the

retrieval of the evidence

circumcision and those with insufficient foreskin removed. The proportion of successful circumcisions was computed only on

In preparation for the TAG meeting, WHO staff searched

clients on whom the device was successfully placed.

the PubMed database for all published studies on the two

• Procedure time was computed for devices as the sum of the

circumcision devices and contacted investigators known to be

preparation and procedure times for placement and removal,

studying the devices in African countries. WHO staff reviewed

not counting the time period between the two. Times were

all published reports. Investigators made available to WHO

measured from start of the surgical procedure to completion of

secretariat confidential final reports from completed studies and

wound dressing (first to last touch) for conventional surgery or

interim reports from ongoing studies for review by the TAG. WHO

to end of device placement (last touch) for device application,

secretariat extracted key features of each study into a standard

but did not include the time for induction of anaesthesia,

format and compiled these to report the most important clinical

where used. Removal times were measured from first touch to

outcomes regarding safety and efficacy of the device in different

completion of wound dressing after device removal.

populations and in the hands of different providers. During the latter part of 2012, a subgroup of the TAG reviewed and

• Time to complete wound healing was defined as the number

commented on all data available. WHO sought clarifications from

of days from the date of conventional surgical circumcision

the study investigators where necessary.

or device placement (not from the date of intended or actual device removal) to the first date when complete wound

As the review of the clinical data by the TAG informs the

epithelialization was observed. Not all study teams used

development of guidance on use of devices, the process followed

identical definitions of complete wound healing, and the long

was similar to that recommended by the WHO Guideline

intervals between visits in some studies prevented a precise

Development Committee, including specifying outcomes of

estimate of the duration of healing.

interest. The evaluation criteria were in line with those identified

• Pain was measured in most studies using a Visual Analogue

in the Framework (1). External audits conducted either on

Score (VAS) with a range of 0–10, where 0 corresponds to "no

behalf of the study sponsor or by a team designated by the WHO

pain at all" and 10, to "worst pain imaginable", with clients

secretariat independently verified the quality of the research

shown pictograms for six different rating levels (Figure 3), with

study and the completeness of the data and reports.

text usually translated into the local language. Depending on the study and the follow-up schedule, the pain assessments

standardization of the priority outcomes

were made at specified time points, such as before or during device placement; specified times after placement; while

The TAG meeting evaluated the devices on the basis of the

wearing; before, during and after removal; and at selected

following critical outcomes and definitions:

follow-up visits. Additionally, some studies assessed the

• Eligibility for male circumcision with the device. All men

duration of the pain. Not all studies assessed pain at the same

must be screened for medical eligibility for circumcision, in

time points; the most comparable times have been selected

particular the absence of any penile abnormalities and current

in order to facilitate comparisons between devices and with

genital infections. For a particular device, use may be further

conventional surgical circumcision.

restricted due to: a) additional anatomical reasons, such as

Figure 3: Visual analogue pain scale and pictograms

phimosis (inability to retract the foreskin), a narrow foreskin opening or a short frenulum; or b) technical reasons that preclude device placement such as unavailability of a correct device size or inability to complete the device placement procedure. Therefore, device eligibility was defined as the proportion of men who met the criteria for conventional surgical circumcision, who were also eligible for circumcision with the specific device and in whom the device could be successfully placed.

definitions and classification of adverse events

• AEs resulting from insufficient or inadequate instructions for

use, deployment, implantation, installation, or operation, or

Although there had been attempts to standardize terminology

any malfunction of the investigational medical device; and,

and classification of adverse events (AEs) in studies of

• Any event resulting from use error or from intentional misuse

conventional male circumcision and circumcision devices, the

of the investigational medical device.

classification schemes evolved as more information about the types and timing of AEs became available. The different

In consideration of the above international definitions and the

mechanisms of action of the devices and the differences from

importance of ensuring a uniform classification that can be

conventional surgical circumcision techniques have led to

applied to clinical research on male circumcision, the WHO TAG

differences in the types of AEs and characterization of the AEs.

closely followed GHTF definitions and the following principles

This required that all observed AEs be reviewed and classified by

(for the two circumcision devices for which data were available

the TAG in a uniform manner. In doing so, the TAG was guided by

for review as well as other devices that may become available

internationally recognized principles and definitions of AEs and

with different mechanisms of action):

serious adverse events (SAEs).

• Any untoward medical occurrence, unintended disease or

The Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF) (9) and the

injury, or untoward clinical signs (including an abnormal

International Organization for Standardization define an AE as:

laboratory finding) in subjects, users or other persons, whether

"Any untoward medical occurrence, unintended disease or injury,

or not related to the conventional surgical procedure or to the

or untoward clinical signs (including an abnormal laboratory

medical device used for performing or assisting in the male

finding) in subjects, users or other persons, whether or not

circumcision procedure was considered an AE.

related to the investigational medical device". This definition

• Any AE that was definitely not related to the circumcision

includes events related to the investigational medical device or

procedure or to handling or operating the medical device was

the comparator and events related to the procedures involved.

not considered further.

In addition, an SAE is defined as an AE that:

• Any AE that satisfied the GHTF definition of an SAE was

considered a serious adverse event (SAE).

1) led to a death; or,

• Any AE not classified as an SAE but that required an

2) led to a serious deterioration in the health of a patient, user,

intervention by a health care provider or medication

(parenteral, oral or topical) was considered a moderate AE.

a. resulted in a life-threatening illness or injury

• All other AEs were considered mild AEs. None of these events

b. resulted in a permanent impairment of a body structure or

would require any intervention.

In order to compile AEs over the different clinical studies and

c. required inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of

circumcision procedures, each AE was classified according to its

existing hospitalization

underlying cause or clinical presentation. It is important to note

d. resulted in medical or surgical intervention to prevent

that the classification adopted is designed to assess and compare

permanent impairment to body structure or a body function.

complications that occurred during the clinical research on male circumcision devices. While the overall principles underlying the

The International Organization for Standardization document

classification are likely to apply to programmes, the details will

14155 additionally defines an adverse device effect as an AE

have to be assessed for relevance in classifying AEs that occur in

related to the use of an investigational medical device, which

male circumcision programmes. Table 3 lists all AEs observed to

date according to category.

clinical evaluation of the shangring

Some clients with moderate or severe phimosis required a small dorsal slit to be made in the foreskin to facilitate eversion over

1.Overview of the studies

the inner ring (range across studies of 10%-28% of men).

The spontaneous detachment study showed that, if the device

The TAG reviewed clinical data on the safety, efficacy and

is not removed as scheduled at seven days, the device begins

acceptability of the ShangRing from studies conducted in China

to detach spontaneously and may come off without removal by

and three countries in Africa. Table 4 summarizes the studies

a medical provider. Partial detachments appear to be painful,

conducted in five sites in Africa (in Kenya, Uganda and Zambia).

cause discomfort as the partially detached device may snag and

Early studies in China demonstrated that the device was safe

cause tearing of tissue and bleeding. Therefore, the device should

when applied under local anaesthesia by skilled providers in

ideally be removed at seven days.

Chinese study participants (ages 5 to 95 years across studies), resulted in a neat and complete circumcision, and was potentially

faster and simpler than conventional surgical circumcision, as no

The overall mean placement time was 6.4 (SD 3.8) minutes,

suturing was required for haemostasis or wound closure. These

excluding the time for injection and induction of local

studies formed the basis for proceeding in a stepwise manner to

anaesthesia. The mean removal time was 3.1 (SD 1.8) minutes.

clinical research in African countries where public health male

The total of the mean placement and removal times (mean

circumcision programmes are being implemented.

10.3 minutes) was less than the mean procedure time in the

In its review of evidence, the TAG placed emphasis on the studies

randomized comparison with conventional surgery in Kenya and

conducted in the African region, which provided directly relevant

Zambia (mean 20.3 minutes).

information on the clinical performance of the device when

used in public health HIV prevention programmes: two initial safety and efficacy studies, two randomized controlled trials and

Adverse events in all the African ShangRing studies combined

two field studies. All the studies conducted in Africa with the

are summarized in Table 5. Based on a total of 1983 successful

ShangRing device used the same device design, which differed

device placements, there were:

from the original device only with regard to the mechanism to

• no SAEs—proportion 0.0% (95% confidence interval

secure the outer ring (see Figure 1). Safety and effectiveness

of the ShangRing device have been studied only in men age 18 years and older. There was consensus among the TAG members

• a total of 20 moderate adverse events—proportion

that the range and scope of the studies conducted on the

1.0% (0.6%-1.6%) and

ShangRing met the requirements set forth in the Framework.

• a total of 43 mild adverse events—proportion 2.2%

2. shangring study results

The ShangRing device is designed to avoid the need for haemostasis during surgery and to clamp the skin edges firmly

together to fuse as part of the healing process. Because of

The overall estimated proportion of clients eligible for

the tight clamping mechanism, local injectable anaesthesia

conventional male circumcision who were also eligible for

is required before device placement and then the foreskin

Shang Ring circumcision and in whom the device could be

is cut away distal to the device. The greatest proportion of

placed was 98.8%. The proportion of clients eligible for

moderate AEs was associated with pain during the anaesthetic

Shang Ring circumcision was 99.6%, due to a small number of

administration and device placement, requiring additional

clients excluded for minor foreskin abnormalities (e.g. short

medication for control in some instances, pain while wearing the

frenulum) that precluded device placement. These men could be

device, or partial device detachment or minor wound disruption

circumcised using a conventional surgical approach. Shang Ring

before device removal. Nevertheless, complications requiring

device placement procedures were started in 1998 clients and

intervention were rare (less than 1 in every 100 procedures).

were completed in all but 15 (99.2%) due to correct ring size not being available at the time of the procedure (8), the foreskin

It is important to note that the seven clients (0.4%) in whom

slipped from the outer ring (3), the foreskin was too short (1) or

the device placement procedure was started but could not be

damaged (2), or the outer ring could not be closed (1).

completed were all immediately converted to conventional surgical circumcision. Had facilities not been immediately

successful circumcision

available to safely complete the open circumcision (sterile field,

Circumcision was achieved in all clients on whom the device was

sutures or electrocautery for haemostasis and sutures for wound

successfully placed with the exception of three men (0.15%) who

closure), complications that would have resulted in serious

were considered to have insufficient skin removed.

adverse events might have occurred. A small number of wound disruptions occurred several weeks after device removal; these were clear departures from the normal healing process.

In the randomized controlled trial comparing ShangRing with

A person experienced in standard surgical circumcision must,

conventional surgery, there were no serious AEs, 2 moderate AEs

therefore, be available on site, together with appropriate

(both in the surgery arm) and 23 mild AEs (15 in the ring arm and

instruments and supplies.

8 in the surgery arm) in 197 ring placements and 198 surgical

• Circumcision using the ShangRing was demonstrated to be safe

circumcisions, P=0.40.

and successful in over 99% of clients.

• Healing is by secondary intention. It requires about one

Healing following male circumcision with the ShangRing device

week longer than after conventional surgery. The TAG

is by secondary intention and takes about one week longer

considered that there is a risk of HIV acquisition if men

than with surgery. In the comparative study, the mean time to

engage in unprotected sex before the wound is healed, but

complete healing was 44.1 (SD 12.6) days following ShangRing

the magnitude of risk is unknown. While this is also true of

placement compared with 38.9 (SD 12.6) days following surgery

circumcision by conventional surgery, because of the longer

(mean 5.2 days longer, 95% confidence interval 2.7–7.7 days).

healing time, the group stressed the importance of good

Thus, ShangRing circumcision requires a longer period of post-

counselling about sexual activity and condom use.

circumcision sexual abstinence than standard surgical methods.

• Adverse events associated with ShangRing procedures were

rare. In a total of 1983 successful device placements, there

were no deaths or serious adverse events (95% confidence

The ShangRing device requires injectable local anaesthesia

interval 0.0%–0.2%). The most common AEs were related to

before placement. The pain experienced during device placement

pain. All AEs were managed with, at most, minor intervention

and in the post-operative period is similar to that reported after

and resolved with no long-term sequelae. Although definitions

conventional surgery. Men reported some pain while wearing the

of serious and moderate AEs in the three randomized

device and a somewhat higher rate of pain during erection than

controlled trials that demonstrated the efficacy of male

at comparable times after conventional surgery. There is a risk

circumcision for HIV prevention in Kenya, South Africa and

of minor injury to the penis from the device itself and discomfort

Uganda are not directly comparable to those adopted in the

from catching or snagging the device while wearing it. Partial

device studies, the proportions are in a similar range—0.0%

detachment of the devices is associated with some discomfort

and pain, but this is rare if the device is removed as scheduled

• Phased implementation with careful monitoring and reporting

at seven days. There is short, transient discomfort and pain as

of device events and AEs is recommended in order to

the device is removed. In one study local anaesthetic spray was

better understand the frequency of technical failures of the

used prior to removal. This seemed to lessen but not completely

ShangRing and how best to manage such failures.

– Programmes must conduct active surveillance of the

Key points on the shangring made by the TaG

first 1000 clients to identify and record AEs based on

(Programmatic considerations are included in the next section).

standardized definitions. The active surveillance may change to passive surveillance after the first 1000 clients, if the

The TAG reviewed clinical data on the safety, efficacy and

incidence of events is reassuringly low as determined by

acceptability of the ShangRing device from five studies

independent review. Ongoing reporting of serious adverse

conducted in three African countries that resulted in device

events as part of post-market surveillance will need to be

placements on nearly 2000 men.

• The TAG considered the ShangRing to be clinically efficacious

• The TAG advised that the clinical studies necessary before

and safe for use in men 18 years and older, when the

a device is considered for prequalification by WHO per

procedure is performed by trained providers in public

the Framework for clinical evaluation of devices for male

health programmes. Skills and surgical facilities should

circumcision (2012) have been satisfactorily conducted.

be available to safely convert technical failures of device

• The evaluation, and thus advice on use, is currently limited to

placement to conventional procedures. The TAG recognizes

data on healthy males 18 years and older, as data were not

that this conclusion on clinical efficacy and safety is only one

available on men under 18 years or on men living with HIV.

component of the prequalification decision. The TAG based

• A small proportion of men were not eligible for device

its conclusion on the data currently available. This conclusion

use. Provision of or referral to conventional surgical male

must be reassessed in about one year as more experience with

circumcision would be needed. Some of the cases required

use of the device accumulates in diverse programmatic settings

immediate conversion to a conventional surgical circumcision.

outside the context of studies.

clinical evaluation of the prepex

2.0 (SD 0.8) minutes, placement procedure 1.5 (SD 1.0) minutes, removal preparation 0.4 (SD 0.2) minutes and removal procedure

1. Overview of the studies

2.0 (SD 1.1) minutes. In the two comparative studies, the mean total procedure time (placement preparation and procedure time and removal preparation and procedure time) was 5.7 (SD 1.4)

Table 6 summarizes the eight studies conducted in three

minutes compared with 19.2 (SD 3.9) minutes for conventional

countries, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe (interim analyses on

two ongoing field studies were included). The device was first clinically tested in Rwanda in a study that established the natural

history of the necrotic process in 50 volunteers. A second study investigated alternative forms of topical anaesthesia at the time

AEs occurred in 42 men in whom the device was successfully

of placement before a formal randomized comparison with the

placed (1.7%); the majority of AEs were mild or moderate,

dorsal slit conventional surgical approach was made. The next

while 9 (21%, or 0.4% of device placements) were considered

study to be completed was a field study in Rwanda in which

serious, as prompt surgical intervention was required to prevent

the device was placed and removed by trained nurses instead

potential serious long-term sequelae. The nine adverse events

of physicians. In order to comply with the requirements in the

categorized as serious resulted from device displacements during

sexual activity, masturbation, erection, possible placement

, a second series of studies was independently

error, or accidental dislodging by another person; early removals

conducted in Zimbabwe, starting with a small safety study

(including self-removals) secondary to pain; meatal injury at

followed with a randomized comparison and a second field study.

removal; and difficult removal due to necrotic tissue everted

2. prepex study results

over the elastic ring requiring surgical intervention, and wound dehiscence. Some of the displacements were associated with painful oedema, blistering and swelling as the blood flow

returned to the partially necrotic foreskin and required prompt

The overall estimated proportion of clients eligible for

surgical intervention to remove the foreskin and avoid serious

conventional male circumcision who were also eligible for PrePex

infection or injury to the penis. No mechanical device failures

circumcision and in whom the device could be successfully placed

were reported.

was 92.6%. The proportion of clients considered eligible for PrePex circumcision was 94.1%, due a number of clients excluded

for phimosis, narrow foreskin opening, tight frenulum, or small

Healing following male circumcision with the PrePex device is

wounds on the foreskin or penile shaft. PrePex placement

by secondary intention and takes about one week longer than

procedures were started in 2268 clients and were completed in

with surgery. In the comparative study in Rwanda, the mean time

all but 38 (98.3%) due to narrow foreskin opening (16), tight

to complete healing was 38.0 (SD 12.1) days following PrePex

or short foreskin (15) or adhesions (4), and three clients with a

placement compared with 23.0 (SD 7.5) days following surgery

penis circumference size outside the range of available ring sizes.

(mean 15 days longer, 95% confidence interval 12 to 18 days). In the comparative study in Zimbabwe, the difference in healing

successful circumcision

times was less pronounced, but interpretation of the data from

A total of 2417 PrePex devices were successfully placed in the

this study is limited by the absence of follow-up visits between

eight studies. For a large majority of clients (99.5%), the PrePex

days 7 and 42 post-procedure in the surgical circumcision arm.

circumcision was successful, leaving a neat circumferential

The overall mean healing time after placement recorded over

wound resulting in a final cosmetic appearance without suture

five studies was 42.3 days (standard deviation 7.8 days). Almost

marks. Circumcision had to be completed by conventional

all men healed by 8 weeks. Thus, healing following PrePex

surgery in a total of 12 clients (0.5%)—four removed the

circumcision requires a longer period of post-circumcision sexual

device themselves on Day 1 , two returned to the clinic on Day 2

abstinence than standard surgical methods.

requesting removal because of pain, discomfort or inconvenience, and in five clients the device became displaced on Day 1 (1), Day

2 (2), Day 4 (1) or Day 5 (1), following erection, masturbation,

The PrePex device does not require injectable anaesthesia

sexual intercourse or an assault. In one client surgery under local

during placement. Comparing the pain scores is difficult

anaesthesia was required to remove the band of necrotic foreskin

because the pain control protocols evolved as the studies

that had everted over the outer ring and prevented device

progressed and more information on pain became available.

In none of the studies was any injectable anaesthesia used for placement or removal of the PrePex device (excluding the

men with complications that required surgical intervention).

There was considerable variation in placement and removal

A topical anaesthetic cream containing 5% lidocaine was first

times over the different studies, with more experienced providers

introduced in the Rwanda field study and has been adopted in all

having lower procedure times. After the initial training and

subsequent studies.

familiarization process, mean placement preparation times were

Summary results of the VAS pain scores in the Rwanda studies

personal inconvenience wearing the device. Some of these

showed that pain at the time of ring placement was minimal. The

cases resulted in pain, rapid swelling and/or blistering of the

period of greatest discomfort and pain was in the 3–6 hours after

partially necrotized foreskin tissue, requiring urgent surgical

placement, with ischaemia induced by the device. Most study

intervention by a skilled surgeon in order to avert permanent

participants were provided with analgesics to take as needed at

disfigurement of the penis and/or severe local or systemic

home after placement; pain during the early ischaemic process

infection. In the studies conducted to date, appropriate

appeared to be adequately controlled in a large proportion of

surgical facilities have been available; all cases were

clients with readily available medications such as paracetamol or

successfully managed, with no long-term sequelae.

ibuprofen. There appears to be less pain while the device is worn

• Client instructions must clearly describe safe use of the device,

than at comparable times after conventional surgery, even during

symptoms that may develop with device displacement or early

erections. Study participants reported transient pain (short

removal as well as the possible serious outcomes and surgical

duration but quite severe) during device removal as the elastic

interventions that may be needed if instructions on abstinence

and inner rings were detached from the healing wound.

and wound care are not followed or if the device becomes

displaced (see next section).

Objectively assessing client acceptability in the early research

• The PrePex device was reportedly acceptable to a large

studies is difficult. However, a large proportion of clients

proportion of study participants. In contrast to conventional

expressed satisfaction with the aesthetic result. Pain, discomfort

surgical circumcision and other circumcision devices that

or user behaviour led to device displacements or early removals.

have been reviewed by the TAG, the PrePex device has the

Providers in at least three studies noted a strong odour in several

advantage of not requiring injectable anaesthesia or suturing

clients at the time of removal. Studies with the PrePex assessed

at the time of placement, thus requiring less time for the

loss of working days, which appeared to be fewer than following

procedures and causing less pain.

conventional surgery.

• PrePex providers must be appropriately trained to recognize

the potential serious complications that can occur if the

Key points on the prepex made by the TaG

device is displaced or removed early, and must ensure that

(Key programmatic considerations are noted in the next section.)

such clients are rapidly assessed for appropriate management (within 6–12 hours), including referral when necessary.

The TAG reviewed clinical data on the safety, efficacy and acceptability of the PrePex device from eight studies conducted

• If countries decide to introduce the PrePex device into their

in three countries with device placement on 2417 men.

public health programme, introduction should be done in a phased approach after the device is prequalified.

• The range and scope of these studies met the criteria

• Careful monitoring and reporting of AEs is necessary in order

established in the WHO Framework for clinical evaluation of

to better understand the frequency of device displacement and

devices for male circumcision.

self-removals and how risks can best be mitigated.

• The TAG advised that the clinical studies necessary before a

– Programmes must conduct active surveillance of the

device is considered for prequalification by WHO have been

first 1000 clients to identify and record AEs based on

satisfactorily conducted.

standardized definitions. The active surveillance may change

• Evaluation and any advice are currently limited to healthy

to passive surveillance after the first 1000 clients, if the

males 18 years and older, as the device has not yet been

incidence of events is reassuringly low as determined by

evaluated for use among younger ages or among men living

independent review.

• The TAG considered that there is an enhanced risk of HIV

• About 7% of clients eligible for conventional surgical

acquisition if men engage in unprotected sex before the wound

circumcision could not have the PrePex device placed for

is healed, but the magnitude of risk is unknown. Therefore,

various anatomical or technical reasons, including a narrow

the group stressed the importance of good counselling about

preputial opening or the correct device size outside range

sexual activity and condom use.

of five sizes produced. Circumcision was completed using

• The TAG considered the device to be clinically efficacious in

the PrePex in 99.5 % of clients on whom the device was

male circumcision and safe for use among healthy men 18

years and older when used by trained mid-level providers

• AEs occurred in 1.7% of clients; the majority were mild or

in public health programmes, provided that surgical backup

moderate. AEs in 0.4% were considered serious, and prompt

facilities and skills are available within 6–12 hours to

intervention was required to prevent potential serious long-

manage events that could lead to serious complications. This

conclusion is time-limited and must be reassessed in about one year as more experience with use of the device in diverse

• In a small number of clients (about 1 in every 200), the

programmatic settings is accumulated and reported.

device became displaced and /or was removed (including self-removal) due to client activities, pain, discomfort or

programmatic considerations in developing wHo

guidance on tHe use of male circumcision devices

During the course of the meeting and the session focused on

Considerations related to delivery site requirements that the TAG

programmatic considerations, the TAG noted the following key

identified included:

points. In general, evidence on devices is currently available from use in research conditions, in which many of the providers are

• The unique requirements of a device will need to be considered

highly skilled. As use expands and shifts from study populations

in the context of each type of service delivery site (e.g. fixed,

receiving "ideal care in well-resourced settings" to more real-

mobile, outreach, routine versus campaign).

world conditions, the TAG considered phased implementation

• At the initial introduction of a new device, it is advised to have

critical to determine the best and safest approaches for addition

both conventional surgery and device methods available.

of a new device method. Pilot studies are planned in a number

• A second visit is definitely required for device removal; services

of the priority countries. The information from these studies will

must be organized to meet the requirements of both visits.

further inform the use of the devices. Implementation plans must be tailored to the specific characteristics of each device.

• The type of surgical back-up skills and facilities must be clearly

specified, depending on device type, and available:

Clinical skills and competencies for device placement,

– "Immediate/on-site" surgical skills will be necessary at the

removal and management of AEs should be available within

time of ShangRing placement.

an ‘individual' and/or a ‘team'. For conversion to a surgical procedure after commencement of a device circumcision,

– "Within 6–12 hours timeframe" surgical skills must be

surgical staff may need skills beyond those needed to perform

available during the week that men have a PrePex device in

conventional surgical circumcision. Required clinical skills

situ, in case of an AE requiring urgent intervention.

and training will differ according to device. For example,

• Referral systems and contact numbers should be in place prior

ShangRing placement requires skills similar to those required for

to adding a device to any service.

conventional surgery, but more advanced skills and experience

• For men not eligible for a device (such as those under 18

are required to manage the rare cases when the ShangRing

years old or HIV-positive), service sites must determine if

placement procedure cannot be completed; these skills should be

conventional surgery is to be available on site or through a

available on site. The surgical intervention necessary after PrePex

functioning system of referral to services at another location.

device displacement or self-removal after the ischemic process has started requires a surgeon experienced with managing

• Programmes need to indicate pain management protocols for

swollen tissue and abnormal foreskin anatomy. These skills and

each specific device and for all stages of device use (pre-, in

facilities must be available or obtainable within 6 to 12 hours.

situ, at removal and post removal); these protocols must be

All providers must be knowledgeable and trained to manage

potentially life-threatening complications as well as the expected

Male circumcision is one essential component of the "minimum

and foreseeable side-effects.

package" of services, and all other components also must be available.

Information should be available for providers, including a

• Accurate messaging is needed on care and hygiene, possible

training manual and instructions for use of the device. The EMP

symptoms and management of device use, including the likely

Department stated that the evaluation of the manufacturer's

event of some pain. Symptoms such as pain, odour, bleeding

instructions for use (IFU) is part of the PQ programme. The

and swelling should be clearly described.

IFU should include pictures and step-by-step instructions from

• Clients must also be instructed on safe behaviours while the

beginning to end (placement and removal) and should list the

device is worn, including avoidance of sexual activity and

equipment that is provided in procedure package and additional

masturbation and the risks associated with such activity

accessories that are required. The TAG asked to review the

(with the PrePex risk of displacement, bleeding, swelling and

IFUs prior to a PQ decision. Considering the limits of any IFU,

ulceration and need for surgical circumcision).

programmes will still be responsible for the training and for developing manuals that will address specific issues such as

• If a device displaces or becomes dislodged, clients must know

pain management.

where to return to receive skilled surgical care or referral and transport arrangements to such care, within 6–12 hours.

Client counsel ing and education is an essential activity for good

There are a number of other issues that programmes will need to

clinical practice, informed consent and mitigation of risks related

consider prior to introduction and use of a device, including:

to client behaviours. Client instructions must clearly indicate the process and requirements of use of a specific device. Clients'

• The organization of the supply chain and logistics will be

partners should also be provided instructions. Points that should

needed. Multiple device sizes will be required and must be

be included in client instructions include the following: