Smokefreenurses.org.nz

SMOKING CESSATION

BEYOND THE ABC:

Tailoring strategies to high-risk groups

36 BPJ Issue 64

Smoking rates are declining in New Zealand as more and more people are successfully quitting. However,

rates remain unacceptably high among deprived communities, Māori and Pacific peoples and in people with mental health disorders. It is often helpful to think of smoking as a chronic relapsing disease, thereby acknowledging the difficulties of smoking cessation and the likelihood of relapse. Ideally, health professionals should be providing smoking cessation support in the ABC format to every patient who

smokes, at every consultation. It is also important to individualise cessation support by understanding why

a patient's previous quit attempts have failed and encouraging a wave of social support for future attempts, particularly in groups with high rates of smoking. Health professionals who are able to do this increase the chances that patients will be able to stop smoking long-term.

Identifying groups with high rates of

number of people who attempt to stop smoking by 40 – 60%.4

This means that one extra person can be expected to attempt

to give up smoking for every seven people who are advised to

In New Zealand, smoking rates are falling; daily smoking

do so and offered support in their attempt.4

among all adults was 18.3% in 2006/07, 16.4% in 2011/12 and most recently, 15.5% in 2012/13.1 However, smoking is

Tailoring support to patients by understanding their quit-

analogous to a chronic disease with frequent relapses, and

history and circumstances means that health professionals can

ongoing work is required to continue this downward trend in

increase the chances of the patient's next attempt succeeding.

the number of people who smoke.

It is important to let patients who are quitting know that it is likely that they will lapse. However, behavioural support, e.g.

Smoking rates are substantially higher than the national

Quitline, and pharmacological smoking cessation aids, do help

average, and particularly concerning in:

prevent a lapse in abstinence becoming a return to regular

People who live in highly deprived areas

Māori and Pacific peoples

Current smoking is associated with poverty

People with mental health disorders

Deprivation is strongly associated with smoking in New

Zealand (Figure 1, over page). After adjusting for age, sex and

The good news is that many people who smoke also frequently

ethnicity, a person from one of the most deprived communities

think about quitting, regardless of their background. When

in New Zealand (Decile 10) is over three time more likely to

surveyed, approximately 40% of people who smoke reported

be a current smoker, compared with a person from one of

attempting to quit in the previous 12 months.2 However, most

the least deprived communities (Decile 1).1 Women who live

attempts to quit do not succeed, and long-term success, e.g.

in lower socioeconomic areas are also more likely to smoke

remaining smokefree for at least six months, is only achieved

during pregnancy (17%) compared with pregnant women in

in 3 – 5% of attempts without the support of a health

the general population (11%).5

Smoking rates in Māori and Pacific peoples must be

There are two strategies that health professionals can pursue

in order to increase the number of people who quit smoking

Almost one-third (32.7%) of Māori smoke, a rate more than twice

as high as New Zealanders of European descent, and more

1. Increase the number of people who attempt to quit

than one-third of Māori women smoke during pregnancy.5, 7

Death rates due to lung cancer and smoking-related diseases

2. Increase the success rate of quit attempts

are three times higher in Māori than non-Māori.7 However, it is encouraging to know that most Māori who smoke do want

Brief advice to stop smoking and, most importantly, an offer

to quit. During the five-year period between 2006 and 2011,

of cessation support by a health professional can increase the

it was estimated that almost two-thirds (62%) of Māori who

BPJ Issue 64 37

smoked made at least one quit attempt.7 It is important that

reported that 32% of Tokelauan and 30% of Cook Island people

these previously unsuccessful attempts be acknowledged and

were classified as regular smokers in the 2013/14 New Zealand

lessons learnt when future attempts to quit smoking are made.

census, while 13% of people who identified as Fijian were

It is also good news that the number of Māori youth who have

regular smokers.9 Encouragingly, rates of smoking are reported

never smoked is increasing: for boys from 58% in 2006/07 to

to be declining among Pacific youth. Regular smoking among

75% in 2013/14, and for girls from 52% in 2006/07 to 72% in

Pacific boys aged 15 – 19 years dropped to 13.6% in 2013/14

2013/14.7 Relative to their population size, Māori also tend to

(from 20.1% in 2006/07), and regular smoking among Pacific

use smoking cessation support services more than non-Māori;

girls of the same age fel to 10.3% in 2013/14 (from 21.4% in

from April to June 2014 Māori accounted for almost one in five

Quitline caller registrations.8

Māori who do not smoke are exposed to second-hand smoke

Smoking prevalence increases with severity of mental

more (11.4%) than non-Māori who do not smoke (6.4%).7 This

increases the severity of the negative health effects of smoking

People with a mental health disorder are approximately twice

on Māori children. More than 20% of Māori households with

as likely to smoke as people who do not have a mental health

one or more child have at least one person who smokes inside

disorder and generally, the level of nicotine dependence

the home, compared to under 8% in non-Māori households.7

increases with the severity of the illness.10 Many people with mental health disorders who smoke will require additional

The overall rate of smoking among Pacific peoples is 23%,

support from health professionals to achieve long-term

although this varies greatly depending on sub-ethnicity; it is

Current sm

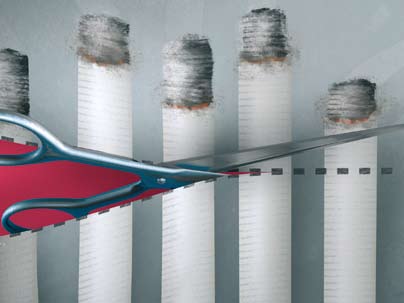

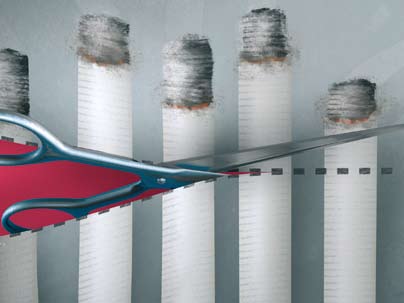

Figure 1: Proportion of people living in New Zealand communities, by deprivation status, who are current smokers,

adapted from NZDep20136

38 BPJ Issue 64

Adapting the ABC to different patient groups

Why does quitting smoking improve

General practitioners are encouraged to Ask about smoking,

mental health?

Briefly advise to quit and offer Cessation support (ABC), to

all patients who smoke, at every consultation.11 Some health

A meta-analysis of 26 studies found consistent evidence

professionals may be reluctant to persistently advise people

that smoking cessation is associated with improvements

to quit smoking due to concerns that their relationship with

in depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life and positive

patients may be damaged. However, it should be remembered

affect.14 This benefit was similar for people in the general

that most people who smoke are open to the idea of quitting;12

population and for those with mental health disorders.14

80% of current smokers report that they would not smoke if they had their life over again.11

The fallacy that smoking improves mental health can be

understood when the neural changes that long-term

"When was the last time you smoked a cigarette?" is a

smoking causes are considered. Over time, smoking

non-judgemental way of enquiring about smoking status in

results in modification to cholinergic pathways in

patients who are known to be smokers.

the brain, resulting in the onset of depressed mood, agitation and anxiety during short-term abstinence from tobacco, as levels of nicotine in the blood drop.14 When

Understand the barriers before you start

a person who has been smoking long-term has another

Understanding why the patient relapsed into smoking

cigarette their depressed mood, agitation and anxiety is

following attempts to quit allows health professionals to

relieved. However, as a person continues to abstain from

provide individual strategies, e.g. encouraging the patient's

smoking the cholinergic pathways in the brain remodel

partner to also take part in the quit attempt if the partner is

and the nicotine withdrawal symptoms of depressed

influencing the patient's smoking status. Having a partner

mood, agitation and anxiety are reduced through

who continues to smoke during pregnancy is said to "almost

abstinence from nicotine. The process whereby people

universally predict" a return to smoking among women who

relieve withdrawal symptoms with a drug, i.e. nicotine,

which then reinforces these symptoms is referred to as a withdrawal cycle and it may also be associated with a

Fear of consequences can encourage smoking

decline in mental health.14

For people whose social life is restricted to family/whanau and neighbours, a fear that quitting smoking can result in being

"left-out" socially is a barrier to quitting.12 Concerns that giving

up smoking will cause illness are also not uncommon, e.g. coughing or chest infections following quitting. Other barriers

The effects of smoking cessation on

to quitting smoking that are frequently reported include: fear

patients with mental health disorders

of weight gain, boredom and the timing of a quit attempt being problematic.12 A patient's individual concerns about

Hydrocarbons and tar-like products in tobacco smoke

quitting need to be addressed when discussing smoking

are known to induce the cytochrome P450 enzyme

CYP1A2.15 When patients taking other medicines that are metabolised by this enzyme stop smoking there

Viewing smoking as a stress-reliever can be a barrier to

may be an initial rise in medicine levels in their blood

as enzymatic activity falls to normal levels. There may

People who smoke often view it as a stress-relieving activity,

be some instances where stopping smoking in a patient

therefore do not want to quit.12, 14 There may also be concern

taking certain antipsychotics (e.g. clozapine, olanzapine,

that quitting smoking will worsen mood in people with a

chlorpromazine, haloperidol) or insulin causes clinically

mental health disorder.14 In fact the opposite is more likely

significant changes in serum concentrations.15 Patients

to be the case: smoking cessation has been shown to have

with insulin-dependent diabetes who stop smoking

beneficial effects on mood disorders, with an effect size equal

should be alert to the symptoms of hypoglycaemia and

to, or larger than, treatment with antidepressants.14 Health

increase their frequency of blood glucose monitoring.16

professionals should acknowledge that a patient's mood may improve in the minutes after smoking a cigarette. However, this is an opportunity to explain to the patient that the reason

BPJ Issue 64 39

they feel better is because they are addicted to nicotine, and

without assessing their readiness to stop smoking. Only

that every puff continues this cycle (see: "Why does quitting

offering cessation support to people with a stated desire to

smoking improve mental health?", previous page). The patient

quit smoking is a missed opportunity for positive change. Also

can then be reassured that al people who break the cycle of

see: "A review of pharmacological smoking cessation aids",

smoking addiction will experience mental health benefits.14

N.B. The doses of antipsychotics used to treat some mental health disorders (and insulin) may need to be adjusted if

A meta-analysis of the effect of cessation support found that

abrupt cessation occurs in a person who is heavily dependent

offers of cessation support by health professionals, e.g. "If you

on cigarettes (see: "The effects of smoking cessation on

would like to quit smoking I can help you do it", motivated

patients with mental health disorders: previous page).

an additional 40 – 60% of patients to stop smoking within six months of the consultation, compared to being advised to quit smoking on medical grounds alone.4 It is important to

From talking to quitting

note that the motivation of patients to stop smoking was not

Motivational interviewing can increase the likelihood that a

assessed before offers of cessation support were made.

patient will attempt to quit smoking and increase the chances of them succeeding.10

Referral to a smoking cessation service is recommended

Quitline is a smoking cessation service which offers phone-

The general techniques of motivational interviewing

based support, six days a week (Monday – Friday 8 am – 9.30

pm, Sunday 10 am – 7.30 pm on 0800 778 778) to all people

1. Expressing empathy

who want to quit smoking. People can self-refer to Quitline or they can be referred by a health professional. Patients can

e.g. "So you've already tried to give up smoking a couple

also be referred electronically if the relevant feature is enabled

of times and now you're wondering if you will ever be

on the practice management system. Txt2Quit support is

available from Quitline directly to mobile phones.

2. Developing the discrepancy between the goal of being

For further information go to: www.quit.org.nz

smokefree and the behaviour of smoking

e.g. "It's great that your health is important to you, but

Aukati Kai Paipa is a free smoking cessation service that

how does smoking fit with that for you?"

delivers face-to-face coaching for Māori from over 30 centres around New Zealand.

3. Rolling with resistance

e.g. "It can be hard to cope when you're worried about

To find your closest provider go to the Aukati Kai Paipa

your mother's health and I realise that smoking is one of

website at: www.aukatikaipaipa.co.nz/contact-us

the ways that you've used to give yourself a break. What other ways do you think you could use? "

Smokefree Communities offers smoking cessation services to people living in the North Shore, Waitakere and Rodney

4. Encouraging self efficacy

areas. Programmes focus on reducing rates of smoking among women who are pregnant and their whanau/family, Asian

e.g. "Last time you didn't think you'd be able to manage

people and their families, and al families with children aged

without smoking at al – and you've actual y gone al week

under 16 years. Smokefree Communities provides support in

with only two cigarettes – what did you do differently this

Chinese, Korean, Burmese and Hindi/Fiji Hindi languages.

time to make that happen?"

To find out more about Asian Smokefree services go to:

A goal of care when consulting with patients who are current

smokers is to negotiate a firm quit date and to agree on "not

one puff" from that point onwards.10

Cessation support is the most important aspect of the

Preventing smoking relapses

ABC approach

Health professionals can discuss strategies with patients to

It is important that cessation support, e.g. referral to smoking

help manage triggers where there is extra pressure to smoke.

cessation service, should be offered to all people who smoke

For example, focus on something that is important to the

40 BPJ Issue 64

patient and incorporate it into a response that they use to decline an offer to smoke, e.g. "No thanks, my daughter has asthma – our home is now smokefree to help her breathing

Incentives to smokefree pregnancies

get better".

Incentive programmes have recently been launched to encourage pregnant women to quit smoking in some

Creating a wave of social support

North Island areas, including Waikato, Counties Manukau

Encourage the person quitting to reach out for assistance

and Northland DHBs. As part of the Waikato programme,

from anyone they know who has previously quit smoking.

vouchers to a total value of $250 are given to Māori or

Peer support for people who are attempting to quit smoking

Pacific women who are up to 28 weeks pregnant, at one,

can take many forms. The rationale is that a person with similar

four, eight and 12 weeks after they have quit smoking.19

life experiences to the person who wants to stop smoking

Vouchers are intended to be spent on items such as

can provide practical tips that fit with their lifestyle. A friend

groceries or petrol; they cannot be exchanged for cash

or family member is also more likely to have regular contact

or spent on cigarettes or alcohol.19 The smokefree status

with the person attempting to quit. Examples of peer support

of the women participating is measured by testing

might be having a coffee or tea together each morning to

exhaled carbon monoxide levels. It was reported that this

discuss any difficulties or temptations, or attending situations

was a positive influence on quit attempts as it provided

together where there may be a strong temptation to smoke,

accountability.20 The Counties Manukau programme

e.g. the pub.

resulted in a 65% quit rate at four weeks and a 60% rate at 12 weeks.20

There is some evidence that peer support may be more

successful when people in deprived communities attempt to quit smoking, compared with people in the general population.17 Some maraes in New Zealand have also run competitions that both challenge people who are quitting smoking to stay smokefree while also supporting each other's quit attempts.

The Quitline Blog is the most popular online smoking cessation

peer support forum operating in New Zealand. People who are attempting to quit smoking can be encouraged to access this forum to receive support at any time of the day or night.

Social networking platforms, e.g. Facebook, can also be used to provide a substitution for social situations where the person has previously found it difficult to resist the temptation to smoke. Social networking is more likely to be used by younger

people who smoke and have regular access to the internet.

The Aukati KaiPaipa Facebook page is available at: www.

Children are a positive and motivating influence

The health-related and financial benefits that the children

of people who smoke gain when their parents quit smoking is a powerful motivating factor.12 In particular, prospective parenthood can provide additional motivation to stop smoking. Having a smokefree pregnancy and then maintaining a smokefree household means that children are less likely to develop middle ear infections, or to have lower respiratory illness, asthma or abnormal lung growth, and have a lower incidence of sudden unexplained death in infancy.11

BPJ Issue 64 41

The cost of smoking just keeps going up

A review of pharmacological

Cost increase is a recognised method for decreasing cigarette consumption. As part of the drive to create a smokefree New

smoking cessation aids

Zealand by 2025, it is government policy that an average

pack of 20 cigarettes will cost more than $20 by 2016, with

Pharmacological aids for smoking cessation can reduce

future price increases beyond this highly likely.18 This policy

nicotine cravings and lessen withdrawal symptoms. An

is supported by the Royal New Zealand College of General

offer of medical assistance may embolden people who have

Practitioners.11

previously attempted to quit smoking without support to try again. Pharmacological aids also reduce the likelihood of a

At a cost of $20, a pack-a-day smoker would be spending

lapse in abstinence becoming a return to long-term smoking.

$140 a week, or more than $7000 per year on cigarettes. The

money that a family/whanau can save by quitting smoking

The important factors to consider when discussing smoking

can, and should, be used to create goals that unite families in

cessation treatment options are the patient's preferences and

their desire to be smokefree. For example, as well as spending

previous experience of smoking cessations aids, the patient's

the extra money on essentials such as clothing, a small weekly

likely adherence to treatment and the possibility of any

treat such as going to the local swimming pool can provide

adverse effects.

an ongoing and tangible incentive to being smokefree. Longer term goals such as saving for a family holiday can also create

family "buy-in" and may help parents remain abstinent from

Nicotine replacement therapy

smoking in the months following their quit date.

The use of NRT approximately doubles the likelihood of a

person being able to quit smoking long-term; one in 14 people who would not otherwise have stopped smoking will do so for

What to do if the patient does have another cigarette?

at least six months following a course of NRT.15 Several studies

If a patient who is attempting to quit reports that they have

suggest that in people who are unmotivated to quit within the

had a brief smoking lapse then it is important that they do not

next month, the use of NRT results in an increased number of

see this as a failure. Support is required to help them avoid

quit attempts and marginally higher rates of abstinence.21 NRT

feelings of guilt and loss of control that can undermine their

may therefore act as a quit catalyst for patients who smoke

quit attempt. Remind patients that many people who quit

and who report that they are not yet ready to stop.21 Offering

experience lapses. Encourage the patient to continue to use

patients who smoke the opportunity to trial different forms of

NRT and any other smoking cessation medicines that have

NRT before they attempt to quit may also improve their choice

been prescribed. Ask the patient to again commit to "not

of NRT and result in better treatment adherence.

one puff" onwards and to ensure that cigarettes, lighters and ashtrays have been discarded.

Most people who are attempting to quit smoking do not use enough NRT.22 Patients who are heavily dependent on cigarettes may gain benefit from increasing the dose of nicotine, e.g. wearing two patches, to replicate the levels of nicotine that reach the brain when they are smoking. Combining NRT products, e.g. using a nicotine patch and nicotine gum, is more effective than using a single NRT product.15 If patients begin to

feel nauseous when using NRT they can be advised to reduce the frequency or dose of the product.22

Subsidised NRT can be prescribed by general practitioners and registered Quit Card Providers. Subsidised supplies of NRT

may also be obtained by general practices using a Practitioner

Supply Order. Pharmacists can supply subsidised NRT that is

prescribed on a normal prescription (maximum quantity 12 weeks) or a Quit Card (maximum quantity 8 weeks) at a cost of

$5; these wil be dispensed in four-week quantities. Pharmacists

are not able to prescribe subsidised NRT unless they are part of a special regional programme, e.g. Canterbury DHB.

42 BPJ Issue 64

Nicotine replacement therapy should be continued for at

is indicated for people who are highly dependent on tobacco,

least eight weeks; the normal treatment course is 12 weeks.23

i.e. smoking within an hour of waking. The gum should be

Patients who feel they are still gaining benefit from treatment

bitten to liberate a peppery flavour. The gum should not be

can continue to use NRT for longer periods.23 If patients wish

chewed continuously as swallowed nicotine can result in

to use NRT as a way of reducing cigarette consumption, prior

gastrointestinal disturbance. It can be placed between the

to quitting, then cigarette use should be reduced to half at six

cheek and gum and chewed again when the taste fades, and

weeks and completely stopped at six months.23

disposed of after 30 minutes.22, 23

In order to determine an appropriate NRT regimen, New

Nicotine lozenges are available in 1 mg and 2 mg formulations.

Zealand guidelines recommend combining the time until the

It is recommended that lozenges be used regularly when

first cigarette with the total number of cigarettes a person

nicotine cravings occur.22 The 2 mg formulation is indicated

smokes each day (Figure 2). The amount of time that passes

for people who are highly dependent on tobacco, i.e. smoking

after waking until a person smokes their first cigarette is a

within an hour of waking.

useful guide when assessing nicotine dependence; New

Zealand guidelines use smoking within an hour of waking

All people who wish to quit smoking can use NRT, including

as a sign of high tobacco dependence,22 smoking within five

people with cardiovascular disease and women who are

minutes of waking is a sign of severe dependence.10

pregnant or breastfeeding, if they would otherwise continue to smoke.22 When discussing the use of NRT with a woman

Nicotine patches are fully subsidised in New Zealand and

who is pregnant or breastfeeding perform a risk assessment

available in 7mg, 14 mg and 21 mg patches. These should be

and consider "Can she quit without NRT?" If not, NRT is safer

pressed in place on dry, clean and hairless skin, and replaced

than smoking. A study involving over 1700 pregnant women

daily.22 Patches may cause some dermal erythema.22 If patients

who used NRT found no significant association between NRT

report disturbed sleep while using nicotine patches then they

use and decreased infant birth weight.24 Pregnant women who

should be removed at night.

are using nicotine patches should remove them overnight.22

Adolescents aged 12 years or over can also be prescribed

Nicotine gum is available in 2 mg and 4 mg formulations. It is

NRT,22 however, the use of NRT alone is unlikely to address

recommended that nicotine gum be used regularly by people

the reasons why an adolescent has begun, and continues to

who are attempting to quit smoking.22 The 4 mg formulation

Smokes after one

Smokes within one

hour of waking

hour of waking

Smokes fewer

Smokes fewer

more a day

more a day

either 2 mg gum or

either 2 mg gum or

either 4 mg gum or

Figure 2: Nicotine dependence assessment algorithm for determining an appropriate NRT treatment regimen, adapted

from "Guide to prescribing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)"22

BPJ Issue 64 43

Table 1: Comparison of smoking cessation medicines that are subsidised in New Zealand23

Funding status* Fully subsidised

Fully subsidised with Special

Authority approval for people

who have tried previously to quit smoking with other medicines†

Efficacy Almost doubles a patient's

Almost doubles a patient's

Approximately triples a

chances of quitting smoking

chances of quitting smoking

patient's chances of quitting

Mechanism of action Atypical antidepressant

Tricyclic antidepressant

Stimulates nicotine receptors

which aids smoking cessation

which aids smoking cessation

less than nicotine, i.e. is a

independently of its

independently of its

partial agonist, thereby

antidepressant action15

antidepressant action15

reducing cravings, and, at the same time, reduces the rewarding sensation of smoking, i.e. antagonist effect.10

Contraindications Lowers seizure threshold

Should not be taken by

None, however, patients and

and should not be taken by

patients: who are acutely

their family/whanau should

patients with acute alcohol or

recovering from a myocardial

be vigilant for changes in

benzodiazepine withdrawal,

infarction, with arrhythmias,

behaviour, thinking or mood,

CNS tumour, eating disorders,

during manic phases of bipolar in particular depression and

bipolar disorder, use of

disorder, with acute porphyria,

suicidal ideation. If this occurs

monoamine oxidase inhibitors

who are breast feeding, or

cease taking the medicine

(MAOI) in the last 14 days, and

who have used a MAOI in the

and seek medical advice

in patients with severe hepatic

Adverse effects In general, bupropion is

Has the potential to cause

Nausea may occur in

considered to be a safer

more harm than bupropion

approximately one-third of

medicine than nortriptyline.

and can be fatal in overdose.15

patients, but this is generally

One in a thousand patients

Adverse effects include: dry

mild and will only be

are expected to have a seizure

mouth, constipation, nausea,

intolerable in a few patients.10

over the course of treatment.25

sedation (which can affect

Use with caution in patients

driving ability) and headaches.

taking antipsychotics due to

Advise patients to avoid

increased seizure risk. Skilled

alcohol as sedation may be

tasks, such as driving, may be

Women who are Avoid during pregnancy

Should only be taken during

Avoid during pregnancy

pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks

44 BPJ Issue 64

Patients with mental May cause levels of citalopram

In general, nortriptyline

See contraindications

health issues to be raised in some patients

should be used with caution in patients thought to be at an increased risk of suicide, or who have a history of psychosis.

Levels of nortriptyline can be increased by two to four-fold, or occasionally more, by the concurrent use of fluoxetine; in this situation nortriptyline dose reductions of 75% have been suggested.

Dosing Initiate one to two weeks

Initiate ten to 28 days before

Initiate one to two weeks

before quit date with one 150

the agreed quit date with

before the quit date, at 500

mg bupropion tablet, daily, for

nortriptyline 25 mg, daily,

micrograms varenicline, daily,

three days, then 150 mg, twice

gradually increase over ten

for three days, increased to

daily. The maximum single

days to five weeks to 75 – 100

500 micrograms varenicline,

dose is 150 mg bupropion,

mg nortriptyline daily, for up

twice daily, for four days, then

and the maximum daily dose is to three to six months. The

1 mg twice daily for 11 weeks.

300 mg bupropion. Treatment

dose should be slowly tapered

The 1 mg dose can be reduced

is usually for seven weeks. For

while treatment is withdrawn.

to 500 micrograms if it is not

people with risk factors for

tolerated. This course can be

seizures or in elderly patients

repeated to reduce the risk of

the maximum daily dose is 150

mg bupropion.

* Subsidy status correct at the time of printing. Check the New Zealand Formulary for latest information.

† Varenicline is fully subsidised with Special Authority approval for people who have tried previously to quit smoking with other medicines and have not

used varenicline in the preceding 12 months. In order to qualify for subsidy patients must:

Indicate that they are ready to cease smoking; and Have enrolled, or about to enrol in a smoking cessation programme that includes prescriber or nurse monitoring; and Have trialled and failed to quit smoking previously using bupropion or nortriptyline; or tried but failed to quit smoking on at least two separate

occasions using NRT, with at least one of these attempts including the patient receiving comprehensive advice on the use of NRT; and

Not have used subsidised varenicline in the last 12 months; and Agree not to use varenicline in combination with other pharmacological cessation medicines; and Not be pregnant; and Not be prescribed more than three months funded varenicline

BPJ Issue 64 45

Nicotine inhalators (15 mg nicotine cartridges) and

nicotine mouth spray (1 mg nicotine per dose) are available

Electronic-cigarettes – the jury is still out

as unsubsidised NRT products. Nicotine inhalators can be puffed on for 20 minutes every hour, and the cartridge

Electronic-cigarettes are a topic in smoking cessation

replaced after three hours.22 One cigarette puff is equivalent

that is evolving rapidly, both in terms of device design

to approximately ten inhalator puffs.22 Nicotine mouth sprays

and evidence of effectiveness. The devices electronically

are also recommended for regular use, or for when cravings

vaporise a solution made up of propylene glycol and/

occur.22 After priming the pump, direct one spray to the inside

or glycerol, nicotine and flavourings, that users inhale

of each cheek. Advise patients to resist swallowing for several

rather than burning tobacco leaves.26 The solution is held

seconds after application to achieve best results.22

in cartridges that are inserted into the device.26 These devices are different to nicotine inhalators.

For further information see the "Guide to prescribing

nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)" available from:

The body of research on electronic-cigarettes is small, but

growing quickly, and opinion is divided as to the potential harms or benefits to personal or public health.27 Currently,

Medicines to aid smoking cessation

no electronic cigarette products have been approved under the Medicines Act for sale or supply in New Zealand

Medicines for smoking cessation should be prescribed in

and therefore it is illegal to sell an electronic-cigarette

combination with behavioural support, e.g. Quitline, to

that contains nicotine.26 It is also illegal for electronic-

improve their effectiveness.10 Table 1 (previous page) provides

cigarettes, with or without nicotine, to be sold as

a comparison of smoking cessation medicines subsidised

smoking cessation aids, or for an electronic-cigarette that

in New Zealand. In general smoking cessation medicines

resembles a tobacco product to be sold to a person under

should not be used by women who are pregnant because

the age of 18 years.26 However, electronic-cigarettes are

the potential risk to foetal development cannot be balanced

available on international websites as smoking cessation

against the known benefits of smoking cessation.15 Some

aids and many people who smoke are interested in using

smoking cessation medicines may not be appropriate for

them for that purpose.

patients with a history of mental disorders.

Electronic-cigarettes are considered by experts to be less harmful than conventional cigarettes, however, short-term adverse effects have been attributed to exposure to propylene glycol including eye and respiratory irritation.28

The aerosol that electronic-cigarettes produce contains

a number of cytotoxic and carcinogenic chemicals that may pose long-terms risks to women who are pregnant.28

These compounds are present at levels one to two orders

of magnitude lower than is present in tobacco smoke, but at higher levels than is found in nicotine inhalers.28

Both the Ministry of Health and WHO recommend that people who smoke should be encouraged to quit using a combination of approved NRT products, i.e. patches, lozenges and gum.26 The Ministry of Health intends to assess new evidence as it arises regarding the safety and appropriateness of the use of electronic-cigarettes as smoking cessation aids.

46 BPJ Issue 64

Māori people to quit smoking. Quitline, 2014. Available from: www.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: Thank you to Dr Brent

Caldwell, Senior Research Fellow, Department of

2014website.pdf (Accessed Oct, 2014).

Medicine, University of Otago, Wellington, Dr Marewa

13. Mullen PD. How can more smoking suspension during pregnancy

Glover, Director of the Centre for Tobacco Control

become lifelong abstinence? Lessons learned about predictors,

Research, University of Auckland and Dr Hayden

interventions, and gaps in our accumulated knowledge. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6 Suppl 2:S217–38.

McRobbie, Senior Lecturer, School of Public Health

and Psychosocial Studies, Auckland University of

14. Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. Change in mental health after

smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ

Technology, Consultant, Inspiring Limited for expert

guidance in developing this article.

15. Ministry of Health (MOH). New Zealand smoking cessation guidelines.

MOH, 2007. Available from: www.health.govt.nz (Accessed Oct,

16. UK Medicines Information. Which medicines need dose adjustment

when a patient stops smoking? 2012. Available from: www.evidence.

1. Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Survey: Annual update of key

nhs.uk (Accessed Oct, 2014).

findings 2012/13. Wellington: Ministry of Health 2013. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-health-survey-annual-

17. Ford P, Clifford A, Gussy K, et al. A systematic review of peer-support

update-key-findings-2012-13 (Accessed Oct, 2014).

programs for smoking cessation in disadvantaged groups. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:5507–22.

2. Borland R, Partos TR, Yong H-H, et al. How much unsuccessful

quitting activity is going on among adult smokers? Data from the

18. Smokefree Coalition. Quitting tobacco would reduce poverty: media

International Tobacco Control Four Country cohort survey. Addiction

release. 2013. Available from: www.sfc.org.nz/media/131211-quitting-

tobacco-would-reduce-poverty.pdf (Accessed Oct, 2014).

3. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term

19. Waikato DHB. Waikato picks up incentive programme for smokefree

abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99(1):29–38.

pregnancies. 2014. Available from: www.waikatodhb.health.nz (Accessed Oct, 2014).

4. Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, et al. Brief opportunistic smoking

cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis

20. Auahi Kore. Counties Manukau smokefree pregnancy incentives

to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction

pilot. Available from: http://smokefree.org.nz/counties-manukau-

smokefree-pregnancy-incentives-pilot (Accessed Oct, 2014).

5. Morton S, Atatoa C, Bandara D, et al. Growing up in New Zealand: A

21. Carpenter MJ, Jardin BF, Burris JL, et al. Clinical strategies to enhance

longitudinal study of New Zealand children and their families. Report

the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation:

1: Before we are born. 2010. Available from: https://researchspace.

a review of the literature. Drugs 2013;73:407–26.

auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/6120 (Accessed Oct, 2014).

22. Ministry of Health (MOH). Guide to prescribing nicotine replacement

6. Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep 2013 Index of Deprivation.

therapy. MOH, 2014. Available from: www.health.govt.nz (Accessed

2014. Available from: www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/otago069936.pdf

(Accessed Oct, 2014).

23. New Zealand Formulary (NZF). NZF v28. 2014. Available from: www.

7. ASH: Action on smoking and health. Māori smoking: fact sheet. ASH,

nzf.org.nz (Accessed Oct, 2014).

2014. Available from: www.ash.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/

24. Lassen TH, Madsen M, Skovgaard LT, et al. Maternal use of nicotine

Māori_smoking_ASH_NZ_factsheet.pdf (Accessed Oct, 2014).

replacement therapy during pregnancy and offspring birthweight:

8. Quitline. Quitline client demographics - quarterly reports April - June

a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr Perinat

2014. Available from: www.quit.org.nz/68/helping-others-quit/

research/quitline (Accessed Oct, 2014).

25. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for

9. ASH: Action on smoking and health. Pacific smoking: factsheet. ASH,

smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD000031.

2014. Available from: www.ash.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/

26. Ministry of Health (MOH). Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS),

including E-cigarettes. MOH, 2014. Available from: www.health.govt.

nz (Accessed Oct, 2014).

10. Zwar NA, Mendelsohn CP, Richmond RL. Supporting smoking cessation.

27. McNeil A, Etter J-F, Farsalinos K, et al. A critique of a WHO-commissioned

BMJ 2014;348:f7535.

report and associated article on electronic cigarettes. Addiction

11. The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP).

2014;[Epub ahead of print].

Tobacco position statement. RNZCGP, 2013. Available from: www.

28. WHO Famework Convention on Tobacco Control. Electronic nicotine

rnzcgp.org.nz/position-statements-2 (Accessed Oct, 2014).

delivery systems: WHO, 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/

12. Research to support targeted smoking cessation: Insights on how

fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6_10-en.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed Oct, 2014).

to encourage people living in high deprivation communities and/or

BPJ Issue 64 47

Source: http://www.smokefreenurses.org.nz/site/nursesaotearoa/BPJ64-smoking-cessation.pdf

Elementalwatson "la" revista ………………. Revista cuatrimestral de divulgación "En el conocimiento y la cultura no Año 4, número 11 sólo hay esfuerzo sino también placer. Llega un punto donde estudiar, o investigar, o Universidad de Buenos Aires Ciclo Básico Común (CBC) aprender, ya no es un esfuerzo y es puro

Gabi Schwaiger-Ludescher Musiktherapie mit einer chronisch schizophrenen Frau – Beispiel einer Auseinandersetzung mit dem Modell der Affektlogik nach Luc Ciompi Luc Ciompis Affektlogik, erstmals herausgegeben 1982, wählte ich zur Grundlage meiner Diplomarbeit, wobei es mir ein Anliegen war, seine Theorie der Entstehung „Schizophrener Verrücktheit" sowie die daraus resultierenden Verständnis- und Behandlungskonsequenzen im Zusammenhang mit musiktherapeutischem Tun zu betrachten. Ich werde in einem ersten Schritt den Begriff Affektlogik sowie das dreiphasige Modell der Schizophrenen Verrücktheit vorstellen. Anschließend beleuchte ich die sich daraus ergebenden